A short history of Byzantium

In 660 BC, Byzantion was an ancient Greek city named for Byzas, one of the many children of Poseidon, there were more than 60 of them.

Byzas was instructed by the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi to settle the land where the Golden Horn meets the Bosporus, and so he did.

In 512 BC, the settlement was conquered by King Darius and the Persians. Notice the coin to the right.

The star and moon was a symbol of Turkey back in the 6th century BC.

The Byzantion Flag of Darius and Persians also carried a Star and Crescent moon.

When the Ottoman Turks occupied the area in the 13th century, they adopted the same star and crescent moon except they turned the symbol clockwise by 90°.

The current Flag/symbol of Turkey is the same Crescent moon, slightly updated.

It could be the oldest Flag symbol still in use.

In 148 BC, the Romans changed the pronunciation to (the more Romans sounding) Byzantium. In 330AD, Emperor Constantine reclaimed the location to build his new Rome, the Nova Roma.

After Constantine’s death, the city was renamed Constantinoupolis in his honor. Constantinoupolis became Constantinople. Constantinople became Istanbul in 1453.

The term Byzantine came back in 1557 when German Historian, Hieronymus Wolf coined it in his book ‘Corpus Historiae Byzantinae’ to describe the art and culture of Constantinople.

The Greek speaking community of Constantinople always referred to themselves as Romans.

Ancient Turkey and Persia was known as Rum and the people known as Rumeli.

In Russian dialect, Caesar came out sounding like Tsar. In German dialect, Caesar became Kaiser.

The term Byzantine now refers to the art and influence of 4th-15th century Constantinople, a richly colored culture of intricate glass mosaics, dark iconic paintings and frescos and colorful fashions of beaded headdresses, enamel jewelry, carved reliefs and embroidered silks.

Even though the style is attributed to Constantinople, the artists also came from Greece, Italy.

Most think the Fall of Rome was in 410, when Alaric and the Ostrogoths took the western city, but most are wrong. The Eastern Roman Empire lasted until 1453 when Mehmet II and the Ottoman Turks broke through the walls and took the city.

Most think of the Byzantine Culture as Greek Orthodox. In some ways they are correct. However, from the 4th to the 6th centuries, the East and West were the same church, same religion, same set of rules.

For all of you still confused by the difference between the Eastern Greek Church and the western Latin Church, let me shed a small explanation.

The ecumenical power of the church was originally split “equally” between 5 Patriarchs: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. The Bishop of Rome was equal to any other Bishop in stature.

That all ended in 523 when the Bishop of Rome, John I, claimed the title of Pope and the head of all Christianity. Pope John reinterpreted passages from the Holy Scriptures to prove that Jesus gave power of the Church to St Peter, who then bestowed it on his successor in Rome. You can understand how the other Patriarchs were a little pissed off.

By 1054, things boiled over when the Patriarch of Constantinople, Michael Cerularius closed all the “Latin” Churches in the city. All talks between the East and the West resulted in the same outcome. Rome demanded to be acknowledged as the head of the entire Christian World. The other 4 Patriarchs gave the Pope the 11th century equivalent of ‘the bird’.

Things got worse. By 1182, the Orthodox Christians of Constantinople massacred and expelled over 60,000 Latin Christians from the city.

According to many historians, this was the catalyst for the 4th Crusade, when in 1204, Venetian Doge, Enrico Dandolo led his troops through the walls of Constantinople, sacked the city and held it for 60 years.

Civility between these two arms of the Christian body have not been the same since.

From the time of Constantine in the 4th century through the time of the Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, Byzantine art flourished throughout both the East and the West.

The two greatest centers of artists were located in Ravenna and Constantinople and Ravenna, which became the capitol city of the Western empire after Rome fell in 410.

Ravenna still has some of the best preserved 5th and 6th century Byzantine mosaics in the world. It’s not a very heavily visited city but the sites are amazing.

The mosaic treatment to the left is the emperor Justinian in the San Vitale church of Ravenna.

When Justinian I died in 565, the western empire splintered apart and divided up amongst the Visigoths, Ostrogoths and Vandals.

The northern Gothic tribes developed the Gothic artistic style arches and stained glass.

Most of Italy remained true to the fresco and mosaic covered walls of the Byzantine movement well into the 13th century.

The Byzantine Churches of Rome

There are over 2.5 million people in Rome. Over 90% of them are Roman Catholic, although less than 30% are practicing. The churches are rarely filled and some of the older ones are rarely open to the public.

I have read there are over 900 churches in Rome although I have a suspicion not all of them even exist any longer. Numbers aside, there are still a lot of churches in Rome.

Many of the older churches have been updated in renovation projects of the ages, altered into the newer Renaissance, Baroque, Mannerist or Roccoco style.

St Peter’s and St John in Lateran are two of the oldest churches in Rome but not much is left from the original design.

The following is a list of what I consider to be the best examples of Byzantine Art still evident in Rome. There are many more examples of wonderful 12th and 13th century mosaics throughout the city but these six examples are my favorites.

The oldest example of Byzantine mosaics can be seen in the Basilica Santa Pudenziana on via Urbana in the Monti. They date back to 390 AD.

Pudenziana was one of the daughters of Saint Pudens, son of a Roman Senator, Christian convert and the father of Saints Prudenziana, Prassede, Timotheus and Novatus. Novato California was named for Saint Novatus.

Sainthood was the Pudens family business.

According to the Christian history, Pudens was Saint Peter’s first baptism in Rome. He was later killed (or martyred) during the reign of Emperor Nero.

The Basilica of Santa Pudenziana sits about 12’ below the street level Via Urbana (the ancient Roman Vicus Patricius), accessible from the Via Urbana by a very accommodating staircase.

Rome might have been rebuilt on the rubble of previous cities, but Santa Pudenziana remains in it’s original position, built over the remains of a 1st century bath house built by Novatus at the Pudens family home. There are two floors of excavations under the church, putting the modern day via Urbana about 30’ above the ancient city.

Although floor mosaics were most commonly made of stone, the wall mosaics were fabricated from either bits of colored glass or clear glass sandwiched over a gold leaf. These tesserae give off a wonderful reflection from the light with gave a more powerful illuminated image of being in the presence of the supreme beings. The colors and shading create a very 3-dimensional appearance.

The Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore was originally constructed around 435 AD. It is still the largest of all Churches in Italy dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

The Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore was originally constructed around 435 AD. It is still the largest of all Churches in Italy dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

The Byzantine mosaics in the church date from the 5th to the 13th century.

The 5th century mosaics are along the nave, below the clearstory windows, and in the triumphal arch that separates the nave from the apse. The original 5th century apse mosaic (now replaced by a 13th century version) once crowned Mary as Queen of all Christendom.

These 5th century mosaics are believed to be copies of illustrations from ancient bibles that don’t exist anymore.

The lighting in the Church is dim at best but if you have a good magnification lens on your camera or binoculars, you’ll be able to get a very good look.

In ancient Roman temples, Ionic Columns were often used in the temples of female deities. It’s interesting that the Christian builders of Santa Maria Maggiore used Ionic columns along the nave of the Basilica.

Santa Maria Maggiore is an amazing place, filled with history.

Aside from the 5th century mosaics, when you look up to ceiling, the gold you’re looking at is the first load of the precious metal brought back to Spain by Columbus in 1492.

It was a gift to the Santa Maria Maggiore by the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V.

Inside Santa Maria Maggiore’s Sistine Chapel (not the same one as the Vatican) is an 18th century Giuseppe Valadier reliquary said to contain fragments of the Holy Crib of the baby Jesus.

The Italians refer to the manger as ‘La Sacra Culla’ (the Holy Cradle). The name has become a great amusement over the years because foreigners tend to pronounce it as ‘La Sacra Culo’, which actually means the Holy Asshole.

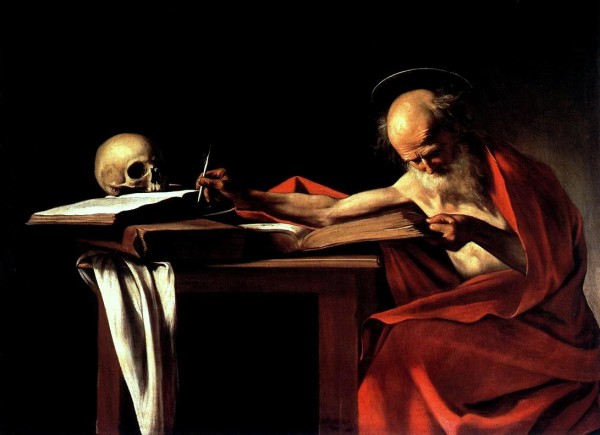

Under the Altar is the burial tomb of Saint Jerome, the 4th century Doctor who translated the Bible into Latin.

Inside Santa Maria Maggiore’s Borghese Chapel is the ‘Salus Populi Romani’, the oldest remaining Byzantine Icon of the Virgin Mary and Child.

And then, there are the burial tombs. Entombed inside the Basilica are 6 Popes including:

Pope Nicholas IV, who restored the Basilica and added the 13th century mosaics.

Pope Pius V, who excommunicated Queen Elizabeth I of England.

Pope Sixtus V, who rebuilt the face of Rome in the 16th century, even though he destroyed the Ancient Septizodium in the process.

Pope Clement VIII, who ordered the philosopher/mathematician, Giordano Bruno, burned at the stake in Campo dei Fiori (Bruno’s statue is the centerpiece of the square.

Pope Paul V, The Borghese Pope who enriched the art and architecture of 17th century Rome.

Pope Clement IX who died of a broken heart in 1669 when he heard the Venetian forces had fallen to the Turks in Crete.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini the master artist who created Italian Baroque sculpture is buried here, so is Pauline Bonaparte, the younger sister of Napoleon (and wife of Camillo Borghese) who is now immortalized as a nude sculpture by Antonio Canova, now in the Galleria Borghese Museum.

But wait, there’s more.

An Underground Museum, opened in 2001, takes you below the Basilica to the excavations of the 1st century Roman Villa that once occupied the site on the Esquiline Hill. The 1st century calendar of the villa is still on the wall.

In another part of the Villa, a tavern keeper kept the names of his bar tabs on the walls. When they paid up, their names were starched off the list. The frescos give a great insight to 1st century life in Rome. In one area you can see how the Romans loved puns and palindromes.

The Museum tour also gets you into the Sala dei Papi and the Capella Sistina and face to face with the 13th century mosaics of the Basilica Façade.

The Church of Santi Cosma and Damiano was the 1st Church to be founded in the Ancient Roman Forum. In 527, Pope Felix IV took a rectangular portion of Emperor Vespasian’s Forum of Peace and converted it into the church.

The Forum of Peace was once attached to the Temple of Romulus (Valerius Romulus that is, the son of the Emperor Maxentius) who drowned in the Tiber in 309. As you walk into the Church, the Temple is through a window on the right hand side.

The Pope dedicated the new church to the twin brothers, physicians Cosmas and Damian of Greece, renown for their healing powers and famous for transplanting the leg of a black Ethiopian man onto the body of a western European white man.

They were tortured to recant their belief in Christianity during the reign of Domitian. They didn’t recant. Instead they became Saints.

Pope Felix IV (most likely) dedicated the Church to the brothers because the Temple of the Castor and Pollux is just across the Roman Forum. Castor and Pollux, known as the Dioscuri, were the sons of Leda and Zeus (disguised as a Swan). They were revered for their help in the final defeat of the Tarquinius Superbus in 495 BC that gave way to the Roman Republic.

Pope Felix was showing the newly converted that Christians also had ‘super powered’ twins.

The (supposed) relics of Cosmas and Damiano are preserved in the crypt below the church.

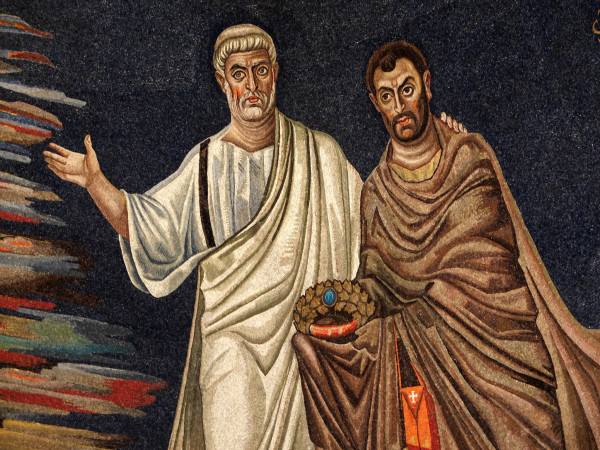

The mosaics, Saints Damian and Cosmas are unique.

Even though the major influence of religious art was coming from Constantinople and Ravenna, these 6th century mosaics were created by Roman artists with more of an emphasis on shadow and musculature. It’s very reminiscent of the ancient Roman style. Even the clothing is more Roman looking.

Even though the major influence of religious art was coming from Constantinople and Ravenna, these 6th century mosaics were created by Roman artists with more of an emphasis on shadow and musculature. It’s very reminiscent of the ancient Roman style. Even the clothing is more Roman looking.

The 6th century Constantinople style was adorned with the fashion of the day, enamel jewelry, decorative headdresses and decorative tunics.

The apse is 6th century. The triumphal arch in front of the apse is actually 7th century.

Christ, dressed in golden robes, is standing on the red clouds of a new dawn. Saints Peter and Paul are standing next to the twin brothers Cosmas and Damiano and Pope Felix is in the scene offering a model of the new church.

Christ, dressed in golden robes, is standing on the red clouds of a new dawn. Saints Peter and Paul are standing next to the twin brothers Cosmas and Damiano and Pope Felix is in the scene offering a model of the new church.

Interestingly, the Christ figure is the only one to sport a Halo. In later Byzantine mosaics, all Saints have heavenly auras.

The legend of Cosmas and Damiano also carried roots in the ancient Greek medical hospital known as the ‘Asklepeion’. If a sick person slept in a church dedicated to the twin brother doctors, they would receive a dream that would tell them how to cure the ailment.

The legend of Cosmas and Damiano also carried roots in the ancient Greek medical hospital known as the ‘Asklepeion’. If a sick person slept in a church dedicated to the twin brother doctors, they would receive a dream that would tell them how to cure the ailment.

The Greek Asklepeion had a very similar procedure. Travelers would visit the Hospital run by the followers of the Asklepios, the god of medicine. They would sleep in the hospital and receive a dream that would tell them how to cure their ailment.

The colors are crisp and amazing. There is a coin operated lamp (€1 euro gets you about 5 minutes of illumination) but you really don’t need the light to appreciate the beauty of the glass tesserae of the mosaics.

Another ‘worth the visit’ at the Santi Cosma and Damiano Church is the 18th century Neapolitan Presepio (Nativity scene). It’s over 45’ long and 27’ deep.

The ‘Presepio’ includes over a hundred figures of men, women, angels, horses, camels and scenery.

In 2008 the baby Jesus was stolen from the Nativity Scene. I don’t know if he was ever returned but now there is a big wall of glass between the visitor and the nativity scene.

I would be nice if the caretakers could clean the glass a little better but it’s still an amazing work of art.

In the 8th century, Constantinople went through a period known as the Iconoclasm, the removal of all Religious Icons (images of the Saints), claiming that the worship of Icons was tantamount to Idol worship. With the exception of some 27 years, Byzantine Iconoclasm lasted from 726 through 842.

The exodus of Byzantine artists from Constantinople was a gift to Rome.

Between 817 and 824, Pope Paschal I gave work to a large number of them, renovating 3 churches in the Byzantine style.

The Basilica of Santa Prassede (Saint Praxedes) became the family church for Paschal I and his mother Theodora.

Prassede was sister of Santa Pudenziana (see the Basilica of Santa Pudenziana above)

The 5th century Basilica di Santa Prassede held the bones of both Saints Pressede and Pudenziana but over the years and renovations they somehow got misplaced.

Santa Prassede was rebuilt in the 8th century, but in the 9th century Pope Paschal I decided to give it a whole new look in the fashion of 9th century Constantinople.

The mosaics in the Basilica are all 9th century and still in perfect condition.

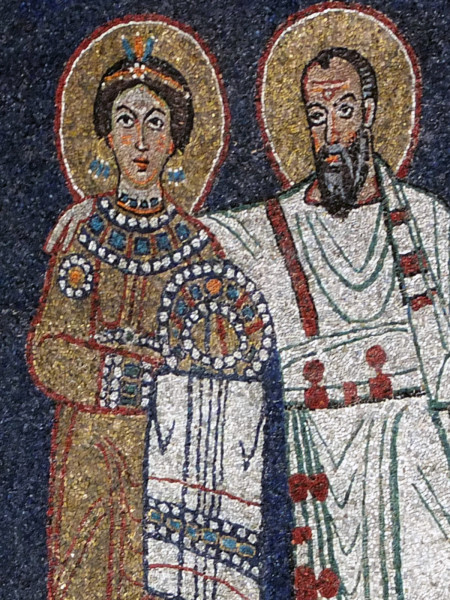

At the time of the renovation to Santa Prassede, Pope Paschal I believed his Sainthood was imminent as soon as he passed into the next world. This might have been a vain conceit on his part, but then if the Ancient Roman Emperors believed they would be deified after death, why not the Popes of Rome?

Paschal understood he couldn’t fully be vested into Sainthood while he was still alive and so he created the symbol of the living Saint, the square blue halo.

He is very easy to spot in the Apse. He is offering a model of the Basilica to Jesus while he stands next to St Peter and St Paul, although to this day, people still look up into the 9th century Byzantine mosaics and ask, “who’s the blockhead?”.

The mosaic over a doorway in the Basilica’s Chapel of St Zeno shows his mother, Theodora (also wearing the square blue halo) seated next to Saints Prassede, Pudenziana and Agnes.

The mosaic over a doorway in the Basilica’s Chapel of St Zeno shows his mother, Theodora (also wearing the square blue halo) seated next to Saints Prassede, Pudenziana and Agnes.

Paschal decided that if he was destined for Sainthood, the right should also be extended to his Mother. Theodora was still alive when the mosaic was created and so, the blue blockhead.

By the way, the other great attraction here (for relic hunters) is the Column of Flagellation, the (supposed) pillar where Jesus was scourged before crucifixion.

By the way, the other great attraction here (for relic hunters) is the Column of Flagellation, the (supposed) pillar where Jesus was scourged before crucifixion.

It was thought to have been brought back to Rome from Constantinople by Giovanni Colonna, the titular cardinal of Santa Prassede, in 1223.

The authenticity of the flogging column has been disputed by historians (and almost everyone else).

It’s not just that the quality and craftsmanship of the pillar seems out of place with the Biblical explanation, but the porphyry Flagellation column (to the right) in the Holy Church of the Sepulchre in Jerusalem seems more convincing.

Religious forgeries and fakes were a big market from the 12th-16th centuries. In those days you just had to rely on faith and the fact that if you didn’t buy it someone else would.

By the way, in 1223, Constantinople was picked clean by the Knights of the 4th Crusade of 1204. After the Latin forces split up the loot, they started selling anything they could find. A good story added more value to the object. Giovanni Colonna bought the Flagellation Column back from Constantinople 19 years after the siege.

The Church of Santa Maria Domnica alla Navicella (5th century) was built over part of the ancient army complex that once housed the Roman 5th Cohort of Vigilies, the fire fighting brigade.

The 18 grey granite columns and capitals supporting the arcade are from an ancient Roman temple that stood nearby.

The porphyry coumns with ionic capitals that hold the triumphal arch in from of the apse are supposedly from the original church.

Although many of the 9th century mosaics remain, much of the Church was renovated in the 16th century by Pope Leo X Medici.

By 817, the church was in need of repairs and became another of the restoration projects of Pope Pachal I.

In the apse, Pope Paschal I is kneeling at the feet of the Virgin Mary, wearing the Byzantine fashion of the day. Pope Paschal once again dons his square blue halo to show he was still alive when the mosaics were created. Paschal is surrounded by the 12 Apostles. Below the mosaic you can see an inscription that spells out PASCHAL.

In the apse, Pope Paschal I is kneeling at the feet of the Virgin Mary, wearing the Byzantine fashion of the day. Pope Paschal once again dons his square blue halo to show he was still alive when the mosaics were created. Paschal is surrounded by the 12 Apostles. Below the mosaic you can see an inscription that spells out PASCHAL.

The church is also known as Santa Maria in Domnica alla Navicella because of the little boat sculpture that sits in front of the church. The boat is a 15th century replica of an ancient statue that once stood there, erected by the sailors who used to live in the area. It was these sailors who were responsible to raise and lower the Velarium (giant fabric awning) over the Coliseum in times of rain or too much heat.

The church is also known as Santa Maria in Domnica alla Navicella because of the little boat sculpture that sits in front of the church. The boat is a 15th century replica of an ancient statue that once stood there, erected by the sailors who used to live in the area. It was these sailors who were responsible to raise and lower the Velarium (giant fabric awning) over the Coliseum in times of rain or too much heat.

The fountain was added in 1931.

The Church of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere was built in 822 by Pope Paschal I after he uncovered her uncorrupted corpse in the Catacombs of San Callisto on the Appian Way.

The Church has undergone many renovations over the years but the apse still has the 9th century Byzantine mosaics.

As with other Pope Paschal churches, Paschal and his square blue halo once again offers a model of the Church to Jesus.

As with other Pope Paschal churches, Paschal and his square blue halo once again offers a model of the Church to Jesus.

Paschal stands to the left of Saint Agatha and St Paul. In the center of the mosaic is Jesus and to his right are St Peter, Valerian (husband of Cecilia) and St Cecilia herself. They are all wearing the Constantinople Byzantine fashion of the day.

Cecilia was a 3rd century Roman patrician who used her home as a refuge for ‘illegal’ Christian prayer gatherings.

When her activities were discovered, she was sentenced to death.

Roman soldiers first tried to boil her to death in the steam room of her Bath House, but she didn’t die.

Next, a Roman soldier hacked at her neck trying to cut if off. After three attempts she was still alive and the soldier ran off.

Cecilia eventually died three days later and was buried with other early Christians in the Catacombs of San Callisto.

When she was exhumed in the 9th century, it was discovered, her body did not deteriorate. It was in, according to the Catholic Diocese ‘in perfect condition, as if she was just laid down to rest’.

Cecilia was brought back to Rome and put beneath the altar of the church, coincidently, on the same location where her patrician house once stood, the same house where she once played music to her guests, the same house where she was tortured and murdered.

Cecilia is the patron saint of music. The Orchestra of the Academy of Saint Cecilia has been one of the best known symphonic orchestras in Italy, since 1585.

Since 2002, the orchestra has been housed in the Parco della Musica, a Renzo Piano designed concert hall in the north of the city.

In 1599, Cecilia’s tomb was opened as part of a reconstruction of the church. The sculptor, Stefano Maderno, who witnessed the opening, confirmed body was still in (relatively) perfect condition under a golden shroud. The Maderno sculpture is modeled after her death pose as he witnessed in her sarcophagus. Her stone neck reveals the slit of the sword that delivered her death.

In 1599, Cecilia’s tomb was opened as part of a reconstruction of the church. The sculptor, Stefano Maderno, who witnessed the opening, confirmed body was still in (relatively) perfect condition under a golden shroud. The Maderno sculpture is modeled after her death pose as he witnessed in her sarcophagus. Her stone neck reveals the slit of the sword that delivered her death.

The church is beautiful and the story is fantastic, but there is more just out the front door.

Ring the bell at the doorway of the Benedictine Convent, just to the left of the church main entrance. One of the Sisters of Santa Cecilia will open the door and guide you down the stairs to see the 1293 frescoed wall of the ‘Last Judgment’ painted by Pietro Cavalini, a contemporary of Giotto.

There is a charge to see the remains of the frescoed wall but it is not much to pay to get so close to such an amazing piece of history. You are literally standing right next to them.

The sisters of Santa Cecilia will also try to sell you their handmade jams and soaps but they’ll understand and smile if you don’t buy them.

INFORMATION

Basilica Santa Pudenziana on via Urbana in the Monti, near the via Cavour metro stop (Blue Line)

Hours: Monday – Sunday; 8:30am -12noon; 3:00pm – 6:00pm

Admission: Free

The Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore

Piazza di Santa Maria Maggiore near the Metro Cavour

Hours: Monday – Sunday; 7:00am -7:00pm

Admission: Free; Museum tour (09:30am – 06:30pm): €5

Basilica Santa Prassede – a few blocks away from the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

Hours: Monday – Sunday; 7:00am -12:30pm; 4:00pm – 6:30pm

Admission: Free

Santa Maria in Domnica alla Navicella – on the Celian Hill behind the Coliseum

Hours: Monday – Sunday; 8:30am -12:30pm; 4:30pm – 7:30pm

Santa Cecilia in Trastevere

Piazza di Santa Cecilia, near the Ponte Palatino

Hours: Monday – Sunday; 9:15am -12:45pm; 4:00pm – 6:00pm

Admission: Free

Santi Cosma and Damiano Church

In the Ancient Roman Forum. The entrance is off the Via dei Fori Imperiali

Hours: Monday – Sunday; 9:00am -1:00pm; 3:00pm – 7:00pm

Admission: Free

You must be logged in to post a comment.