The Walls of Rome

The Servian Walls

If you’re arriving to Rome’s 1930’s Termini Train Station, look to the right as you walk out the front of the station into the Piazza dei Cinquecento, the square named for the 500 Italian soldiers who were wiped out by 7,000 Ethiopians at the Battle of Dogali (Eritrea) in 1887.

If you’re arriving to Rome’s 1930’s Termini Train Station, look to the right as you walk out the front of the station into the Piazza dei Cinquecento, the square named for the 500 Italian soldiers who were wiped out by 7,000 Ethiopians at the Battle of Dogali (Eritrea) in 1887.

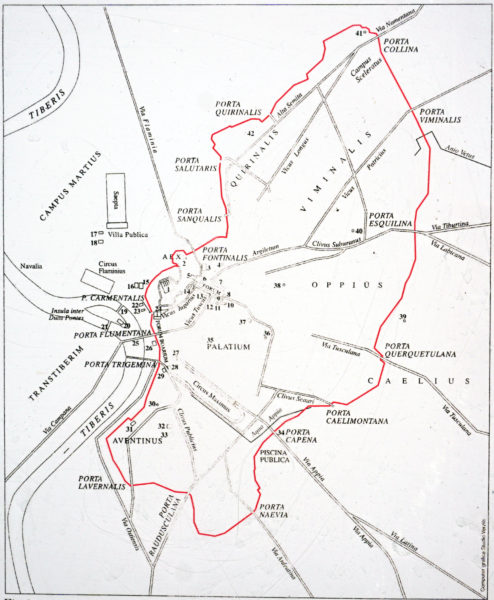

You’ll be looking at the most complete run of the 6th century BC Servian Wall of Rome. When it was completed, the 33’ tall, 12’ thick Servian Wall ran for 7 miles around the ancient city. This section of the wall was rediscovered between 1876-1878 during the construction of the old Termini Train Station.

King Servius Tullius, the 6th King of Rome, who ruled from 575-535 BC, gets the credit for building the walls but the origins probably go back a lot further.

It’s unlikely Rome from 753 BC (the common date of origin) to 575 BC was without any fortifications.

Servius Tillius, the last good King of Rome, was killed by his son-in-law, Tarquinius Superbus (the last bad King of Rome) and his daughter Tullia, who added insult to the murder by running over his dead corpse with her chariot as she fled the scene of the crime.

The wall was breached only once, on July 18, 387 BC, when according to the historian Titus Livy, the Romans, hastily retreating from the Battle of the river Allia, ran back to the city and forgot to lock the gate.

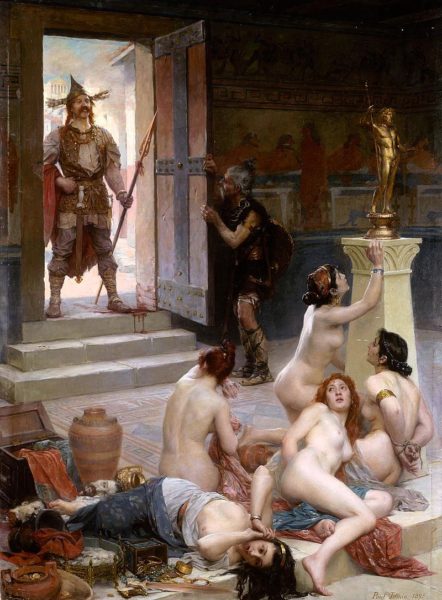

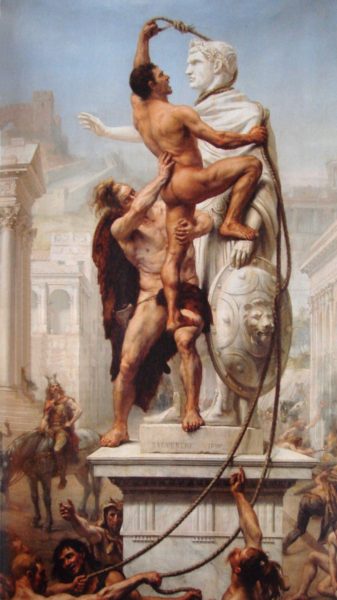

The pursuing warlord, Brennus and his army of Gallic Celts raped, pillaged and burned the city for days. Finally the Romans offered him 1,000 pounds of gold to leave.

According to the legend, Brennus rigged the scales so the ransom would be a lot more than the agreed upon price. When the Romans complained he replied, “Vae Victis.” Woe to the vanquished. The motto became a calling card for the Romans for the next 750 years.

The Servian Wall did prove fortified enough to hold off Hannibal and his forces during the 2nd Punic War.

Hannibal sat atop Surus, his last remaining war elephant at the gates of Rome, but realizing the walls were too much for him, he turned back to Carthage to get reinforcements.

For years afterwards, Romans would yell, “Hannibal ad portas” (Hannibal is at the gates) whenever things looked bad for the Republic or when parents wanted to scare their children into behaving properly.

Most of the Servian Walls is gone. The best sections are here at the Termini Train station but you’ll see a few others in the Aventine’s Piazza Albania or in Largo Magnanapoli near Trajan’s Market.

There are also a few remains at the intersection of via Antonio Salandra and via Giosuè Carducci near Piazza Barberini, in Piazza Manfredo Fanti near the Termini station and in the McDonald’s Fast Food emporium in the lower floor of Termini station.

There are some great photos and descriptions of these wall remnants on the websites of Jeff Bondono and Andrea Pollett.

There were once 15 gates to the Servian Wall. Three of them are still standing.

The ancient Porta Caelimontana bordering on the Caelian Hill was rebuilt in the year 10 AD as the Arch of Dolabella, named for the Consul, Publius Cornelius Dolabella, the nephew of Publius Quinctilius Varus, the Roman General who suffered one of the worst defeats in Roman history when he lost three legions to Germanic tribes in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.

Although the Arch was co-sponsored by another Roman consul, Gaius Junius Silanus, it is possible that Dolabella sponsored a public project one year later in order to help erase the pain of the Varus family stain.

Although the Arch was co-sponsored by another Roman consul, Gaius Junius Silanus, it is possible that Dolabella sponsored a public project one year later in order to help erase the pain of the Varus family stain.

These days it’s a peaceful entrance to the quiet Via di San Paolo della Croce that meanders through the Caelian Hill. If you follow the street, you’ll soon arrive to the Case Romane del Celio, a 3rd century subterranean Roman house. The excavation opened in 2002. It is well worth the visit.

The brick section over the arch was added later in order to accommodate an aqueduct built to provide water to Nero’s Golden Palace. These day you can walk by it and have no idea what it once was. Now that you know, it’s worth a stop.

The Porta Esquilina is the Servian gate that sat at the entrance to the Esquiline Hill. It was rebuilt by the Emperor Augustus around the same time as the Arch of Dolabella.

Around 262, the gate was dedicated as a triumphal Arch of Gallienus, in honor of the Emperor Gallienus and his wife, Cornelia Salonina. Gallienus barely held the Empire together in the late 3rd century. Although he wasn’t a soldier, he spent most of his time as Emperor fighting invasions from all sides of the Empire.

It is possible the Gate was used a Triumphal Arch for Gallienus. Being constantly at war, he did celebrate a long list of victories.

The enemy wasn’t just from the borders of Rome. Gallienus was not a soldier. He was a highly educated and cultured Emperor who had little in common with the military generals who felt it was their right to choose their leader. On a night in September 268, when Gallienus came out of his tent near Mediolanum (Milan) he was attacked and killed by the Praetorian guard. His final insult was to be buried 9 miles south of Rome along Appian Way instead of inside one of the Imperial Mausoleums inside the city.

There were once 2 smaller arches on either side of the Arch of Gallienus but they were destroyed for building materials in the 15th century.

One 3rd remaining gate of the Servian Wall is the Porta Carmentalis, on the via del Teatro di Marcello across the street from the Church of San Nicola in Carcere..

This is a double arch. They are slightly offset because each arch had a different purpose depending on which side of the arch you entered.

One was known as the Porta Scelerata (the cursed Gate), supposedly to named for a military disaster at the Battle of Cremera in 477 BC where 306 brave Romans held off a more powerful Etruscan army. The story might be legend propaganda taken from the famous Greek Battle of Thermopylae which took place around the same time.

The other arch, the Porta Triumphalis could only be entered by someone who was celebrating a military victory or Triumph.

Most believe the Porta Scelerata was the gate entering the city and the Porta Triumphalis was the gate when departing the city.

There are many who have confused the gate to be the Porta Catularia, which also no longer exits. Catularia got its name because red dogs were sacrificed near the gate to appease the anger of the Dog Star to protect the grain during the extreme heat of the summer months.

The Porta Carmentalis gate was hidden by Medieval houses until it was revealed again when Mussolini cleaned the city to give room to the ancient monuments and revealed the ancient gate at the base of the small Monte Caprino.

Monte Caprino is a beautiful walk from the Capitoline Hill towards the Arch of Janus, Temple of Hercules and the Temple of Portuno. It is the back side of the ancient Tarpean rock where criminals of the Roman Republic were tossed to their deaths. These days the Monte Caprino is a famous as gay hook-up place.

One final note on the Servian Walls. The 1st century BC wall behind the Imperial Forum of Augustus, along the Salita di Grillo is old but not as old as the Servian fortification.

This wall separated the Imperial Forum from the notorious riffraff of the Suburra, the ancient red light district.

The Aurelian Walls

By the 3rd century (AD), Rome’s boundaries doubled and the population swelled close to 1,250,000 million people. The city had outgrown the Servian Walls. Emperor Aurelian (Lucius Domitius Aurelianus) was a military Emperor who had successful campaigns against the Germanic and Persian invasions. It was his 5 years of wars (270-275) that inspired him to build a bigger and better fortification to the city.

By the 3rd century (AD), Rome’s boundaries doubled and the population swelled close to 1,250,000 million people. The city had outgrown the Servian Walls. Emperor Aurelian (Lucius Domitius Aurelianus) was a military Emperor who had successful campaigns against the Germanic and Persian invasions. It was his 5 years of wars (270-275) that inspired him to build a bigger and better fortification to the city.

Like so many other Emperors of the Roman Empire, Aurelian was eventually killed by his soldiers. He was basically set up. Some of his enemies forged a document that included the names of high ranking officers that were about to receive an Imperial death notice from the Emperor. They acted first. The walls weren’t completed until 282, under the emperor Marcus Aurelius Probus, who, you guessed it, was killed by his personal guard.

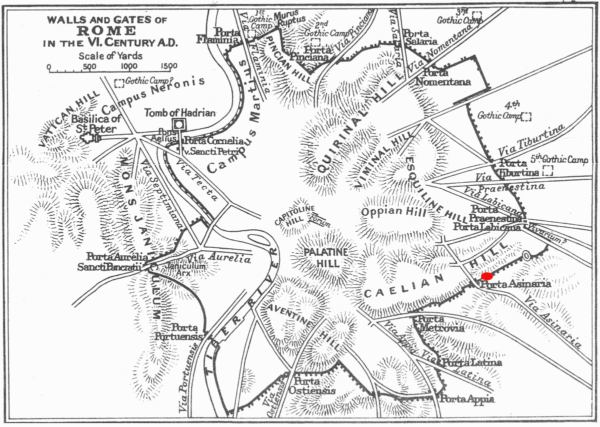

The walls were doubled in height to 52’ tall in the 4th early 5th centuries but by the early 5th century, the barbarians were at the gates.

Theodosius I, the last Emperor to rule both the Eastern and Western parts of the Empire, split the rule after his death in 395. His son, Acadius, took over the seat of the Eastern Empire in Constantinople. His son, Honorius, took the seat in Rome. Theodosius entrusted the guidance of the young Honorius to his favorite General, Flavius Stilicho.

It was Stilicho who raised the defense of the Aurelian Walls and it was Stilicho who kept the peace with the invading Goths. Eventually, Honorius got too jealous and in 408, he removed Stilicho from power and had him executed. Less than 2 years later, Alaric and the Visigoths sacked the city.

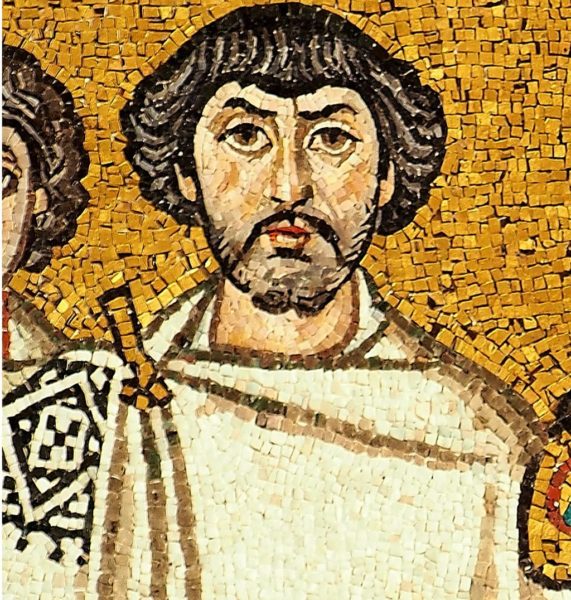

In the 6th century, the Eastern Emperor Justinian I attempted to reclaim the ancient Roman empire and piece it all back together. He sent his Generals Belisarius and Narses to Italy. Although they never conquered France, Britain and Spain, by 560, they did put most of the Roman Empire back together, but when Justinian and Belisarius died in 565, the Empire was carved up forever.

The Leonine Wall

In the 9th century, Pope Leo IV reinforced the fortifications around the Vatican Hill after the Basilicas of St Peter’s and St Paul’s Outside the Walls were sacked by Aghlabids Islamic raiders from Northern Africa in 845.

In the 9th century, Pope Leo IV reinforced the fortifications around the Vatican Hill after the Basilicas of St Peter’s and St Paul’s Outside the Walls were sacked by Aghlabids Islamic raiders from Northern Africa in 845.

The ‘Saracens’ never did get through the Aurelian Walls. Both of the Basilicas at this time were outside the Walls.

The Porta Cornelia, later called the Porta Aurelia and even later called the Porta di San Pietro is long gone. It once sat in front of the bridge of the Ponte Sant’Angelo when the Mausoleum of Hadrian (now the Castel Sant’Angelo) was incorporated into the Aurelian Wall.

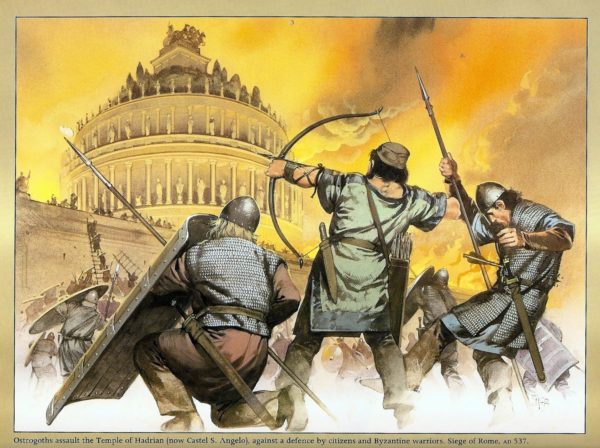

During the Gothic Wars of 535-554, the defenders of the Gate fought off the Gothic invaders from the gate, hurling down marble statues or whatever they could loosen from the ancient tomb down onto the invading Ostrogoths.

During the Gothic Wars of 535-554, the defenders of the Gate fought off the Gothic invaders from the gate, hurling down marble statues or whatever they could loosen from the ancient tomb down onto the invading Ostrogoths.

The walls still surround the Vatican Hill and the Castel Sant’Angelo.

It was most likely here where the unpaid armies of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V entered the gate in 1527 and inflicted the worst pillage and sack of the city in the city’s history.

Nothing was spared, not churches or Shrines, not shops or homes, not food, not even the people. It’s been estimated between 6,000 and 12,000 citizens of Rome were killed.

Janiculum Wall

In 1643, Pope Urban VIII (Barberini) built another stretch of fortified walls along the right bank of the Tiber known as the Janiculum Wall. It was basically a protection from the Farnese family and their allies; Venice, France and Tuscany. Even though Urban VIII managed to defeat the Farnese Duke of Parma, he realized the victory would have grave international retaliation. And so, after removing sections of the old Aurelian wall, he rebuilt the area with the new Janiculum Wall. The main gates of this wall at the Porta Portese and the Porta San Pancrazio. I’ll get to them later.

From the 3rd to the 17th century, the Aurelian Walls protected the city. There have been as many as 18 Gates, although 4-5 of them were used only for military access. Some of the Gates have been altered to make room for the modernization of the city. Some were dismantled. However 12 of them still remain in very good condition.

Rome had a population of around 800,000 before the 1st sack of the city in 410. By the time of the 1527 sack of the city there were barely 55,000 people in the city. By the time the Italian Unification of Rome was completed, Rome’s population was around 200,000. Today, Rome’s population is around 2.8 million.

The Gates of Rome

To get a good overview of what the gates of Rome this website of maquettes by André Caron of Québec, Canada gives an excellent visual idea of how they once appeared. His models of ancient Rome are wonderful. This is the website.

The Porta Salaria

I’ll begin the tour of the Gates of Rome with one of the most famous entrances, the Porta Salaria built along the Quirinale Hill, the northern fortifications of Rome on the via Salaria, the salt road that connected the city to the Adriatic Sea. Salt was a major commodity used for everything from spice to preservation of foods.

The Gate doesn’t exist any longer, but this was where Alaric and the Visigoths breached the wall on August 24, 410. This event has erroneously been called the Fall of Rome. It’s not the case. The Western Roman Empire continued until 476. The Eastern Roman empire continued until 1453.

Porta Salaria replaced the ancient Porta Collina built by Servius Tillius in the earlier Servian Wall. In the 4th century it was known as the Porta Sancti Silvestri, named after the Pope Sylvester I who was buried in the Catacombs of Priscilla, about 3km from here. Sylvester was the Bishop of Rome from 314-335. According to legend he cured the Emperor Constantine of leprosy by baptising him. However, this is a legend. Most believe Constantine was never baptised.

Porta Salaria was finally dismantled in 1921 and replaced with the Piazza Fiume, a small square honoring the Italian soldiers who fought and died during World War I in the Battle of the Piave River and the victory of Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia).

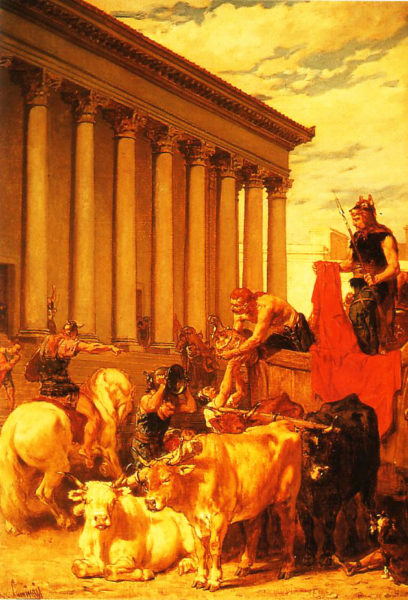

After Alaric and the Visigoths came through Porta Salaria in the year 410 they looted the city for 3 days, taking gold, silver and gems. They broke into the Mausoleums of Augustus and Hadrian and stole the funerary jars, spilling to the ground the ash remains of 3 centuries of Rome’s greatest families. Romans were tortured into revealing the whereabouts of their wealth.

Porta Salaria did indeed fall to Alaric and his army but many believe the Gate was actually opened to them by some disgruntled Roman slaves. The city’s food supply was cut off and although the wealthy still had enough, the poor were starving.

The Emperor Honorius (reign 393-423) goes down as one of the worst Emperors in Roman history. He wasn’t even in Rome when it was sacked. Honorius was in Ravenna at the time Alaric entered the Porta Salaria. Ravenna the Governing Capital of the empire since 402.

According to the historian Procopius, one of the royal eunuchs, the poultry tender, informed the Emperor that Roma had perished. Honorius cried out that it had just eaten out of his hands. When the eunuch explained that the city of Rome had fallen and not the Emperor’s pet chicken, Honorius was greatly relieved.

In 455, Pope Leo I opened the Gates to Genseric and the Vandals in order to reduce the amount of destruction to the city. The Gates were spared but the city was so completely looted of all riches, it gave rise to the word vandalism.

It’s not clear which gates were opened to the Vandals but it would most likely have been Porta Salaria or one of the northern gates.

The Salaria Gate was damaged during the Gothic Wars (535-554). It held against the siege weapons of the 536 Ostrogoth attack but the damage was great. It was rebuilt by Belisarius in 547 after the Byzantine Army routed the Ostrogoths out of Rome.

In 1870, the gate was blown up by the Army of the Italian Unification. It was rebuilt in 1873 but finally torn down in 1921. Rome’s affair with the Porta Salaria had reached the end of the line. It was replaced with the Piazza Fiume, honoring the Italian soldiers who fought and died during world War I in the Battle of the Piave River and the victory of Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia).

The Porta Pia

In 1559, Pope Pius IV (Medici) was elected as the leader of the Catholic Church. Among his civic improvements in the city, he commissioned the new Porta Pia, a gate equidistant between the Porta Salaria and the Porta Nomentana. After it’s completion in 1564, the Porta Nomentana was closed. Today there is nothing left of Porta Nomentana. You can barely make out one of the towers of the old gate as a part of the foundation in the British Embassy of Rome on via Nomentana.

The design and execution of the gate in 1561 went to the then 86 year old Michelangelo Buonarroti. There is a story that the Pope received three designs for the Gate and chose the least costly version.

Michelangelo died in February of 1564, three years after he started working on the Porta Pia. By the time the gate was completed in 1565, much of the original design was altered.

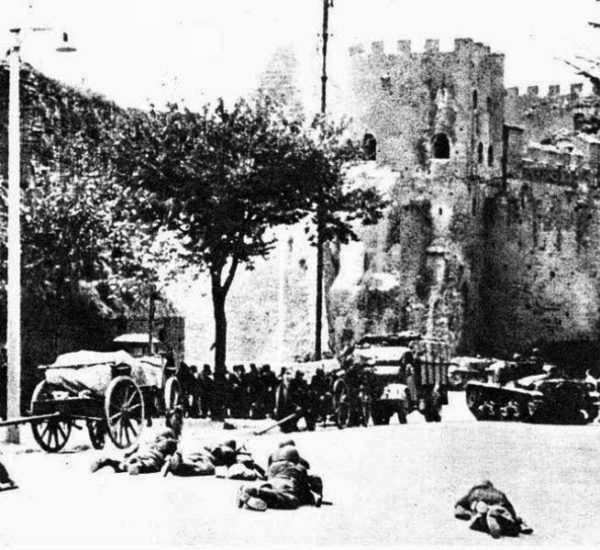

The outer gate was added in 1868 as a defense against the Italian Unification army but on the 20th of September 1870 the Porta Pia fell to the Risorgamento, the rise of the new Italy. The Vatican was the last hold out to Italy’s Unification.

For Italian patriotism, the 20th of September marks the anniversary of the breach of the Porta Pia. The road leading to the gate is called the via 20 Settembre in honor of the date.

The walls and the Gate were defended by barely 13,157 soldiers against the fast moving sharp shooting Bersagliere Infantry, the Pride of Piemonte. Together with the rest of the Italian Unification Army, they amassed over 50,000.

The fight at this point was merely symbolic. Pope Pius IX (Mastatai-Ferretti) wanted a show of resistance just to establish the historical point that the city was not handed over to the new government. It took 3 hours of canon fire to break through the wall. There were 68 casualties; 49 soldiers from the Italian Unification Army and 19 from the Papal guards.

The Bersagliere Museum inside the Porta Pia is a curious couple of rooms filled with costumes, dioramas, photos and written memories of the September 20th victory. There is also an interesting scale model of the famous battle.

The Bersagliere Museum inside the Porta Pia is a curious couple of rooms filled with costumes, dioramas, photos and written memories of the September 20th victory. There is also an interesting scale model of the famous battle.

In 1926, Porta Pia was the site of another historic event when the Italian anarchist Gino Lucetti, threw a bomb against the car carrying Il Duce, Benito Mussolini. The bomb failed to detonate. Lucenti was sentenced to 30 years in prison. He died in the prison on the island of Ischia in a 1943 allied air raid.

Recently the remains of what many consider to be the Campus Sceleratus (the evil fields) were dug along the via 20 settembre, near the Porta Pia. Campus Sceleratus was where Vestal Virgins who broke the vow of chastity were buried alive.

The Porta Tiburtina

From the Porta Pia walk towards the Castro Pretorio Metro station and follow Viale Castro Pretorio to the Porta Tiburtina. You can see the remains of the Porta Praenestina on via Monzambano just off the Viale Castro Praetorio. This was a gate along with the Porta Clausa and Porta Principalis Dextra were primarily used for military access to the Castro Pretorio, the Praetorian camp set up by the Emperor Tiberius in the 1st century. Constantine disbanded the Praetorian guards in the 4th century.

Porta Tiburtina on the via Tiburtina (very close to the Termini Train Station) is one of the oldest gates in the city. The gate started out as a 1st century BC arch built by Augustus to handle the confluence of three aqueducts; Aqua Marcia, Aqua Julia and Aqua Tepula. The Arch was restored several times in the 1st and 2nd centuries as testified by the dedications still visible over the arch. In the 3rd century it was incorporated into Aurelian’s wall in the 3rd century.

Porta Tiburtina on the via Tiburtina (very close to the Termini Train Station) is one of the oldest gates in the city. The gate started out as a 1st century BC arch built by Augustus to handle the confluence of three aqueducts; Aqua Marcia, Aqua Julia and Aqua Tepula. The Arch was restored several times in the 1st and 2nd centuries as testified by the dedications still visible over the arch. In the 3rd century it was incorporated into Aurelian’s wall in the 3rd century.

This photo is of the gate from the inside of the wall. It is the better side for photographs. The exterior entrance to the gate is the more important side but it is obscured by a protective iron gate.

However, even if you can’t get a good photo, you can see the ancient majesty of this 1st century BC arch. The top channel for the Aqua Julia is dedicated to Augustus. The dedication lists the accomplishments of Augustus (Pontifex Maximus, Council for the 12th time, Tribune for the Plebs for the 19th time, imperator for the 13th time) and how he restored the channels of all the aqueducts in 5 BC.

The middle channel for the Aqua Tepula (from 212) is dedicated to Emperor Caracalla (Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus). Caracalla claims, after his many titles, to have repaired the Aqua Tepula by cleaning the source and cutting through mountains to bring the new Aqua renamed Antoniniana, after himself, of course.

The 3rd and lowest channel for the Aqua Marcia (from 79) is dedicated to the Emperor Titus, son of Emperor Vespasian. Titus lists all his political achievements and claims the restoration of the Aqua Marcia after it was destroyed by time and restored back to good use.

It is often called the Porta San Lorenzo because of its proximity to the Basilica of San Lorenzo Fuori le Mura (St Lawrence Outside the Walls). Yes, this is the Basilica that purports to contain the tomb, the relics and the iron grill that caused the death of Saint Lawrence in the year 258.

Many people also refer to the gate as Capo di’ Bove or Porta Taurina because the Augustan arch in the center of the gate is decorated with bull skulls wearing garlands, a decorative motif known as a bucranium, a reference to blessing of sacrifice. The bull skull motif was brought back as a decorative motif by Andrea Palladio in the 16th century.

Many people also refer to the gate as Capo di’ Bove or Porta Taurina because the Augustan arch in the center of the gate is decorated with bull skulls wearing garlands, a decorative motif known as a bucranium, a reference to blessing of sacrifice. The bull skull motif was brought back as a decorative motif by Andrea Palladio in the 16th century.

One last note about the Porta Tiburtina. This is the site where in 1347 the populist leader Cola di Rienzo won his biggest victory against the wealthy Barons of Rome.

One last note about the Porta Tiburtina. This is the site where in 1347 the populist leader Cola di Rienzo won his biggest victory against the wealthy Barons of Rome.

This was the first populist revolt in Rome in over 1400 years. Another wouldn’t come to the city until 1922 when Mussolini’s Black Shirts marched on Rome.

Cola di Rienzo was run out of Rome soon after the fight at the Porta Tiburtina. He came back in 1354 but the same mob he once led against the wealthy class turned on him and killed him as he tried to escape.

From the Piazza di Porta San Lorenzo, walk through the train station to the other side and turn left down via Giovanni Giolitti, past the ancient Tempio di Minerva Medica and into the Piazza di Porta Maggiore.

Porta Maggiore

Porta Praenestina (now called Porta Maggiore) was built in the year 52 by the Emperor Claudius as an Aqueduct arch. This is not only the best preserved 1st century city gate but also a great example of how the aqueducts were integrated into the city walls.

Porta Praenestina (now called Porta Maggiore) was built in the year 52 by the Emperor Claudius as an Aqueduct arch. This is not only the best preserved 1st century city gate but also a great example of how the aqueducts were integrated into the city walls.

Two sources of water, the Aqua Claudia and the Anio Novus both ran through this arch. The arch and the Aqueduct system was fortified in 271 and incorporated into the Aurelian Wall fortifications.

The columns holding up the pediments between the arches look eroded by time, but according to Yale Art Historian Diana E. E. Kleiner they were created this way back in the 1st century as a design choice by Claudius. It was kind of modern art of the 1st century.

Over the years the arch was restored by Emperor Vespasian and then his son, Emperor Titus. The Latin inscriptions on the attic are dedications by Claudius, Vespasian and Titus on how they built and repaired the arch, paying all expenses with their own money.

In 52 AD, the inscription tells how Claudius, at his own expense, brought the Aqua Claudia from the Caeruleus and Curtius springs. In 71 AD, Vespasian adds that he too, at his own expense, restored the confluence of the Aqueducts that had fallen to disrepair for nine years. In 81 AD, the Emperor Titus added, also at his own expense, that he further repaired and restored the structure that was built by Claudius and repaired by his father Vespasian.

Behind Porta Maggiore is the Tomb of the Baker, the burial tomb of Marcus Virgilius Eurysaces , a former slave who became a freeman and then a very wealthy baker. He built the tomb for himself and his wife, Atistia sometime between 50BC and 20BC. Even though it sits next to the Porta Maggiore, it predates the arch by close to 100 years. This (along with the Pyramid of Cestius at Porta San Paolo) is one of the best preserved funerary monuments of ancient Rome.

Behind Porta Maggiore is the Tomb of the Baker, the burial tomb of Marcus Virgilius Eurysaces , a former slave who became a freeman and then a very wealthy baker. He built the tomb for himself and his wife, Atistia sometime between 50BC and 20BC. Even though it sits next to the Porta Maggiore, it predates the arch by close to 100 years. This (along with the Pyramid of Cestius at Porta San Paolo) is one of the best preserved funerary monuments of ancient Rome.

When it was built, the Tomb of the Baker sat a fairly good distance outside of the Servian Wall. When Aurelian incorporated the Arch of Claudius and the confluence of aqueducts into his new Porta Maggiore, the Tomb of the Baker remained outside the gate, but just barely.

From Piazza Maggiore, head down the via Eleniana to the Basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. The Basilica was built on the location of the Praetorian Guards since the time of Emperor Tiberius in the 1st century. When Constantine disbanded the Praetorians in the 4th century he claimed the site for his Villa where he lived with his mother, Helen.

Follow the road past the Basilica and take a left turn on the via Nola. You’ll see the remains of the ancient Castrense Amphitheater . It was the second largest amphitheater (next to the coliseum) in Rome. These days it’s mostly used as a garden for the Basilica.

If you walk along the Viale Castrense near Santa Croce in Gerusalemme you can still see the curve of the large amphitheater.

Follow the Viale Castrense and in less than 10 minutes you’ll arrive to the Porta Asinaria and the Porta San Giovanni.

Porta Asinaria

The Porta Asinaria (Gate of the Donkeys) was actually a minor gate in the fortifications.

The Porta Asinaria (Gate of the Donkeys) was actually a minor gate in the fortifications.

The original gate was just a small opening used by farmers on donkeys coming into the city.

The twin towers that flank the gate were added in the 5th century when the Basilica of St John in Lateran became the Papal seat of Rome in the 4th century.

The twin towers that flank the gate were added in the 5th century when the Basilica of St John in Lateran became the Papal seat of Rome in the 4th century.

This minor gate has played an important role in some of the great shakeups of Rome’s history.

This was the Gate where, in 536, General Flavius Belisarius entered an exhausted and badly beaten Rome.

The Gothic wars of 535-554 was the longest onslaught against the fortifications of Rome.

In 537, Vitiges and the Ostrogoths destroyed many of the aqueducts leading into Rome, removing most of the city’s water supply. The forces of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I under the command of Belisarius held the city from the attacking Goths, but on December 17, 546, while Belisarius was fighting the Goths outside the walls, Totila and his army of Ostrogoths came through the Porta Asinaria.

As in the 410 breach of the Porta Salaria, some disloyal and disgruntled Roman soldiers opened the gate for Totila. The city was sacked and plundered until the reinforcements of Byzantine troops arrived and put them on the run.

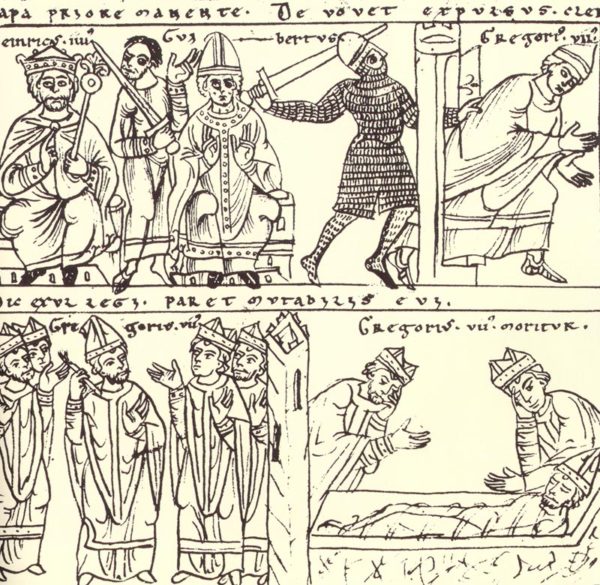

In June of 1083, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV came through this gate when he removed Pope Gregory VII and set himself up in the Papal quarters of the Basilica of St John in Lateran. After Pope Gregory VII excommunicated Henry IV, the Holy Roman Emperor responded by proclaiming Clement III as the new Pope.

In May 1084, the Norman, Robert Guiscard (known as the Weasel) came through the Asinaria Gate with 36,000 Norman troops and defeated Henry IV, rescuing Pope Gregory VII and sacking the city, just because he could. Pope Gregory accompanied Robert Guiscard south to Salerno. Both Guiscard and Pope Gregory died a year later, 2 months apart.

In 1574,Pope Gregory XIII closed the Porta Asinaria when he inaugurated the brand new Porta San Giovanni, the glorious new entrance to the Basilica of St John in Lateran.

Porta Asinaria was left to decay over the years until the restoration of the 1950’s. It was restored again in 2004. The Donkey Gate is now one of the prettiest gates in Rome.

Porta San Giovanni

In the late 16th century, Pope Gregory XIII had some of the best architects in the world in Rome. Civic architectural renewal was popular with the Popes of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. The credit for the Porta San Giovanni usually goes to Giacomo della Porta, although some argue it was actually Giacomo del Duca, an architect who collaborated with Michelangelo on the Porta Pia in 1561.

In the late 16th century, Pope Gregory XIII had some of the best architects in the world in Rome. Civic architectural renewal was popular with the Popes of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. The credit for the Porta San Giovanni usually goes to Giacomo della Porta, although some argue it was actually Giacomo del Duca, an architect who collaborated with Michelangelo on the Porta Pia in 1561.

Porta San Giovanni commands some of the worst auto traffic in the city. Pope Gregory XIII was right, the Porta Asinaria could have never handled this kind of traffic.

The most wonderful anecdote about the Porta San Giovanni surrounds its festival known as “The nights of San Giovanni”. It’s the Summer Solstice festival, the victory of light over darkness, or good over evil. The Festival of St John (San Giovanni) is on June 24th. The night before the festival is also known as La notte delle Streghe (the Witch’s night), similar to Halloween.

According to the believers, on this night, the earth is filled with strange magic powers. Herbs picked on this night have super powers. Washing your face with dandelion leaves picked on this night could cure ailments, rubbing freshly picked mint on your body could enable true love, lying down in the dew of the grass could ensure pregnancy, St John’s Wort rubbed on the body could prevent misfortune, eating zucchini flowers on this night brings good luck and countless herbs and roots picked on this night would be the ultimate talisman to protect against evil.

It’s been said that the ghost of Herodias, the wife of Herod Antipas, who convinced her husband to decapitate John the Baptist (St John) would haunt the gate every year on the night of June 23rd. Some have even witnessed the ghostly shape of Salomé dancing by the gate.

It’s been said that the ghost of Herodias, the wife of Herod Antipas, who convinced her husband to decapitate John the Baptist (St John) would haunt the gate every year on the night of June 23rd. Some have even witnessed the ghostly shape of Salomé dancing by the gate.

At one time Romans would light bondfires by the gate to scare her away. These days there is just a candle lit procession, sometimes led by the Pope.

Another Roman tradition by the Porta San Giovanni is the “Salita degli Spiriti” where the Romans would gather for the tradition of eating stewed slugs. Snail vendors set up their booth in front of the Basilica of San Giovanni.

The explanation is that the horns of the slugs represented conflict, antagonism and hatred. By eating them, the person would consume and digest all the resentment, cleaning themselves of all hostility. Enemies would become friends after a good bowl of stewed snails.

Porta Metronia

South of Porta San Giovanni is the Porta Metronia, a Gate was not well fortified and consequently bricked up during the Middle Ages. As traffic in Rome became more congested, the Gate was completely removed and replaced with 4 large arches over the streets leading in and out of the Piazzale Metronia.

South of Porta San Giovanni is the Porta Metronia, a Gate was not well fortified and consequently bricked up during the Middle Ages. As traffic in Rome became more congested, the Gate was completely removed and replaced with 4 large arches over the streets leading in and out of the Piazzale Metronia.

If you visit the Servian Gate now known as the Arco di Dolabella, it’s a 5 minute walk down the via Della Navicella. Stop in the Church of Santa Maria in Domnica alla Navicella. It one of the best Byzantine Churches in Rome. Then walk a few minutes more and you’ll be in Piazzale Metronia.

The walk along the wall from Porta Metronia to Porta Latina is along a peaceful park filled with families and joggers. The park was once the ancient Pomerium, a sacred space inside the wall protected by gods, demons and other supernatural powers. It was forbidden to build structures or carry weapons in the Pomerium.

Legend states that Remus was killed by his brother Romulus for carrying weapons through the Pomerium.

These days, the laws of the Pomerium along the Aurelian Wall are still maintained. There are no dwellings, no buildings and no weapons. There is a sign posted explaining to all visitors that they are entering a sacred Pomerium.

Porta Latina

Moving south, we come to the Porta Latina, the Gate that led to the Basilica of San Giovanni a Porta Latina.

Moving south, we come to the Porta Latina, the Gate that led to the Basilica of San Giovanni a Porta Latina.

According to the early Christian historian, Tertulian, the Porta Latina is where St John the Evangelist survived his martyrdom of being boiled in oil in the year 92.

Not wanting to give the Romans another try, John packed up and moved to the island of Patmos. It was on the island where he created the Book of Revelation, commonly known as the Book of the Apocalypse. In John’s telling, the world is destroyed by the Whore of Babylon riding a seven headed beast signaling the second coming of Jesus.

Although many modern day Christian Fundamentalists believe the Apocalypse is imminent, for John the Evangelist, it actually happened.

John was born in the year 15. He witnessed the destruction of Jerusalem in 66. He lived through the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79. It’s quite understandable how he thought the world was coming to an end. It is understandable how he thought the Whore of Babylon was Rome itself. It might have also had something to do with the food, wine and herbs he was consuming on the island of Patmos.

The 16th century Chapel of San Giovanni in Oleo (St John in Oil) behind the Porta Latina, is the commemoration of the event. It’s an unassuming small chapel and no-one is really sure who designed it but credit has been given to some of the best architects of the day; Donato Bramante, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Baldassare Peruzzi.

The 16th century Chapel of San Giovanni in Oleo (St John in Oil) behind the Porta Latina, is the commemoration of the event. It’s an unassuming small chapel and no-one is really sure who designed it but credit has been given to some of the best architects of the day; Donato Bramante, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Baldassare Peruzzi.

Like the rest of the wall, the height of the gate wall and towers were doubled at the beginning of the 5th century, However, the gate itself was actually lowered to accommodate a sliding armored door, a new feature at the time.

From the Porta Latina, turn right and follow the Wall along the Viale delle Mura Latine. In about 6 minutes, you’ll arrive to the Porta San Sebastiano.

Porta San Sebastiano

Porta San Sebastiano is the largest of the Aurelian gates and the only gate that allows you inside, up to the towers and along the walls. It’s amazing, it’s free and by the way, it’s closed on Mondays.

Porta San Sebastiano is the largest of the Aurelian gates and the only gate that allows you inside, up to the towers and along the walls. It’s amazing, it’s free and by the way, it’s closed on Mondays.

In 2001, when a 40’ section of the wall collapsed, the entire 1,320’ walk along the San Sebastiano walls were closed to the public.

In 2001, when a 40’ section of the wall collapsed, the entire 1,320’ walk along the San Sebastiano walls were closed to the public.

In 2006 it all reopened and the views are incredible. The rest of the museum includes photos and explanations of how the walls were built and restored.

The ancient looking mosaics on the floor inside the Porta San Sebastiano are from the 20th century.

The ancient looking mosaics on the floor inside the Porta San Sebastiano are from the 20th century.

They were added around 1940 when Ettore Muti, hero Aviator of World War I, notorious womanizer and one time Secretary of the Fascist Party used the Porta San Sebastiano as his personal villa.

By 1942, Muti’s relationship with Mussolini deteriorated and on August 24th, 1943 a group of policemen came into his villa and arrested him. He was taken into a forest and executed.

Originally named Porta Appia, the gate opened onto the via Appia Antica, one of the 1st of the great ancient Roman highways.

The name of the gate was changed to Porta San Sebastiano during the Middle Ages, a tie in to the Catacombs dedicated to Saint Sebastian a couple kilometers down the Appian Way.

The Porta San Sebastiano still opens out to the Via Appia Antica, the Queen of Roads that was once filled with funerary monuments and glorious villas. These massive remains still decorate the road. It’s a great walk, especially on Sundays when much of the via Appia Antica is closed to traffic.

On the exterior right side of the San Sebastiano Gate is a carving of Saint Michael, etched in 1327 as a commemoration of the Colonna family’s victorious Ghibelline army against the Guelph armies of King Robert of Anjou (King of Naples) and Rome’s Orsini family, both loyal to the Pope John XXII of Avignon.

On the exterior right side of the San Sebastiano Gate is a carving of Saint Michael, etched in 1327 as a commemoration of the Colonna family’s victorious Ghibelline army against the Guelph armies of King Robert of Anjou (King of Naples) and Rome’s Orsini family, both loyal to the Pope John XXII of Avignon.

Ghibellines were loyal followers of the Holy Roman Emperor. Guelphs were loyal to the Pope. Wars between these two political factions lasted from the 11th through the 14th centuries.

It was basically an age old rivalry between the Houses of Bavaria and Swabia. The Guelphs (from Bavarian Welfs) were wealthy merchant families in larger cities. The Ghibellines (from the Waiblingen, the ancestral home of the Hohenstraufen Swabians) were mostly land owners near smaller cities.

Things got even more confusing when the seat of the Papacy moved from Rome to Avignon, France between 1309 and 1377.

San Sebastiano’s Gate was redesigned in 1536 by Antonio da Sangallo the younger as a Tribute Gate for the visit of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, the same Emperor who was responsible for the 1527 Sack of the City, the worst destruction in the entire history of Rome. In 1536 a greatly embarrassed Charles V came to Rome in an attempt to smooth things over with the Vatican.

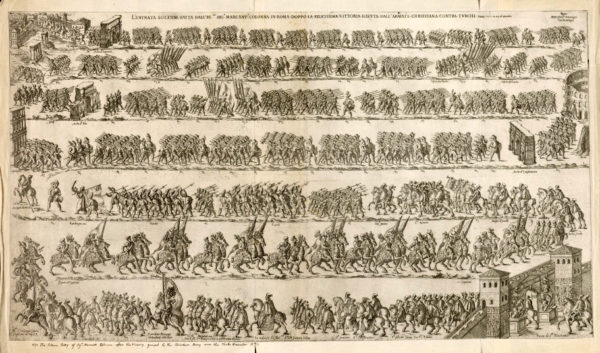

The San Sebastiano Gate was spruced up again for the December 4, 1571 triumphal procession of Marcantonio Colonna, the hero of the Battle of Lepanto in the Gulf Of Corinth against the Ottoman Turks. This was the first major naval defeat of the Ottomans. The Vatican League was mostly sponsored by Spain and consequently the Spanish Admiral don Juan of Austria. However, home in Rome the victory was celebrated for home boy Marcantonio Colonna. When he returned home, Pope Gregory XIII (Boncompagni), the namesake of the Gregorian Calendar, gave Colonna the title of Captain General of the Papal armed guards.

It was a traditional Roman Tribute that included 170 chained Turkish prisoners in tow. This was the last traditional Roman Triumph that included prisoners in chains.

Just inside the gate is a much older arch known as the ‘Arch of Drusus’, named for Nero Claudius Drusus, brother of the Emperor Tiberius and second son of Livia Drusilla, the wife of Emperor Augustus.

Drusus took the title of Germanicus after conquering the German tribes north of the Rhine. In a true moment of historical irony, the victorious Drusus Germanicus fell off his horse while subjugating the conquered Germans and died shortly after.

It seems appropriate that Drusus Germanicus would have a triumph in Rome after his great victory, but most historians believe the Arch is actually part of the 2nd century Aqua Marcia built by the Emperor Caracalla to bring in more water to his baths a short walk down the road.

Close to the Porta San Sebastiano (and the Porta Latina) are two of the best examples of early burial tombs in Rome. The 4th century BC Tombs of the Scipio Family and the Columbarium of Pomponio Hylas are off the tourist trail but they are very easy to get to. You can buy your tickets (5 euros) from inside the Museo delle Mura inside of the Porta San Sebastiano.

The Tombs of the Scipioni are famous for one of the greatest Roman Generals of all time, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, who defeated Hannibal at the Battle of Zama and consequently won the 2nd Punic War for Rome against Carthage. However, Scipio Africanus was never buried here, nor was his adopted grandson, Scipio Aemilianus, the victorious General of the 3rd and last war with Carthage.

The actual sarcophagus of Scipio Barbatus, who died in 306 BC, is in the Vatican. The one on display in the Tomb is a very good copy.

The columbarium underground burial vault is from the 3rd century BC. It is a small quadrangular room dug into the soft tufa stone filled with alcoves for funerary urns. In the center there is a large circular pillar, also used for funerary urns of Scipio family members.

The columbarium underground burial vault is from the 3rd century BC. It is a small quadrangular room dug into the soft tufa stone filled with alcoves for funerary urns. In the center there is a large circular pillar, also used for funerary urns of Scipio family members.

A little further down the road is the Parco degli Scipioni, a small park with a few swings for children, a walk for dogs and strange looking shed that from first appearance looks like a tool shed.

It is in fact the entrance to the Hypogeum Columbarium of Pomponio Hylas, a 1st century freedman who used the Columbarium for himself, his wife Pomponia and his family. The Columbarium was built and used between 14-54 AD.

It is in fact the entrance to the Hypogeum Columbarium of Pomponio Hylas, a 1st century freedman who used the Columbarium for himself, his wife Pomponia and his family. The Columbarium was built and used between 14-54 AD.

In one of the later funerary altars of the Hylas Colombarium is the funerary urn of a woman named Paezusa. In life she was the hair dresser (ornatrix) to Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the Emperor Claudius and his 3rd wife Messalina and the 1st wife of the Emperor Nero. He killed her and sent her head to his girlfriend, Poppaea. Nero killed Poppaea (by accident) a few years later.

In one of the later funerary altars of the Hylas Colombarium is the funerary urn of a woman named Paezusa. In life she was the hair dresser (ornatrix) to Claudia Octavia, the daughter of the Emperor Claudius and his 3rd wife Messalina and the 1st wife of the Emperor Nero. He killed her and sent her head to his girlfriend, Poppaea. Nero killed Poppaea (by accident) a few years later.

The guided tours are in Italian. Some of the guides do know a little English and can usually answer a few questions. You can purchase your tickets in the Museo delle Mura of the Porta San Sebastiano ( each) and a guide will be provided.

Sangallo Bastions

As you exit the Porta San Sebastiano, turn right and follow the wall down the Viale di Porta Ardeantina. It’s an easy 30 minute walk from the Porta San Sebastiano to the Porta San Paolo along the Viale di Porta Ardeantina. In about 15 minutes you’ll come to one of the most impressive fortifications of the wall created by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger in the 16th century.

As you exit the Porta San Sebastiano, turn right and follow the wall down the Viale di Porta Ardeantina. It’s an easy 30 minute walk from the Porta San Sebastiano to the Porta San Paolo along the Viale di Porta Ardeantina. In about 15 minutes you’ll come to one of the most impressive fortifications of the wall created by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger in the 16th century.

Around 1537, Pope Paul III (Farnese) called on architect, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger to fortify the walls against an imminent Ottoman attack. The Turks were already in Hungary and Croatia and making their way to Vienna and Venice. Their goal was to conquer Rome and replace the Christian Church with Islam.

Pope Paul III was more concerned with fortifying the walls around the Vatican but he did make a gesture to improve the rest of the city wall, at least till he got the bill.

A short walk later, you’ll arrive to the Porta Ardeantina.

Porta Ardeantina

These days Porta Ardeantina is just a small doorway in the wall, a slight jog off the wall just before you arrive to the massive thoroughfare known as the via Cristoforo Colombo. The gate has no towers and no defenses. It was most likely a secondary gate used for the military. Now it looks like a small doorway.

These days Porta Ardeantina is just a small doorway in the wall, a slight jog off the wall just before you arrive to the massive thoroughfare known as the via Cristoforo Colombo. The gate has no towers and no defenses. It was most likely a secondary gate used for the military. Now it looks like a small doorway.

Four large arches were taken out of the Aurelian Wall to create access for the via Cristoforo Colombo. If you take a taxi from the Fiumicino (Leonardo Da Vinci) airport you’ll most likely go through the arches without ever knowing you’re entering the city through the ancient wall.

Four large arches were taken out of the Aurelian Wall to create access for the via Cristoforo Colombo. If you take a taxi from the Fiumicino (Leonardo Da Vinci) airport you’ll most likely go through the arches without ever knowing you’re entering the city through the ancient wall.

Porta San Paolo

Across the via Cristoforo Colombo and down the viale Marco Polo and you’ll arrive to the Porta San Paolo.

Across the via Cristoforo Colombo and down the viale Marco Polo and you’ll arrive to the Porta San Paolo.

It was once known as the Porta Ostiensis that connected ancient Rome to the ancient seaport of Ostia by way of the via Ostiense. It still does.

The name of the Gate was changed to Porta San Paolo Gate in the Middle Ages as a tie in to the proximity to the Basilica San Paolo fuori le mura (St Paul outside the walls).

The gate towers were enlarged in the early 5th century by Emperor Honorius’ Magister Militum, Flavius Stilicho. The double entrance to the Gate was added by Emperor Justinian’s Magister Militum, Flavius Belisarius in the 6th century.

In the 1920s, the walls connecting the Gate were removed to allow for automobile traffic. In the 1930s Mussolini spruced up the gate as part of his plan to refresh the ancient monuments of the city. It was all part of his urban restoration to highlight the ancient monuments and link the glory of ancient Rome to the new glory Mussolini hoped to bring in the 20th century.

Mussolini intended to make Porta San Paolo part of the grand tour of his (Esposizione Universale Roma) expo that never happened. The San Paolo Gate would lead the visitors to the archeological site of ancient Ostia.

In 1924 he started construction on the Ostiense train station across the street from the San Paolo Gate. The train station was used for Hitler’s arrival to Rome in 1938 but the 1942 Expo never happened. By 1942, Mussolini was on the run.

In 1943, the allied raids on Rome bombed the sections of wall that once connected the gate to the Pyramid of Cestius. After the war, the rubble was cleaned up and now both the gate and the Pyramid are stand alone pieces.

In 1943, the allied raids on Rome bombed the sections of wall that once connected the gate to the Pyramid of Cestius. After the war, the rubble was cleaned up and now both the gate and the Pyramid are stand alone pieces.

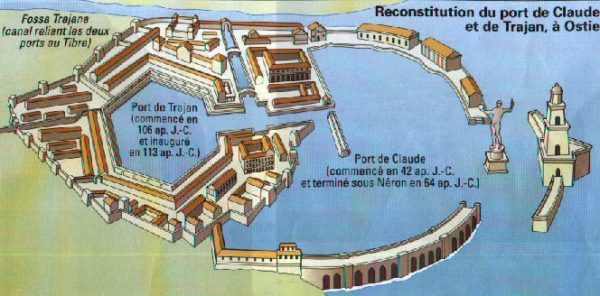

In 1954 the Via Ostiense Museum opened inside the Porta San Paolo. There are a few rooms filled with prints and models illustrating the commercial importance of the road between Ostia and Rome. There are a few models here of Ancient Ostia and the Ports of Claudius and Trajan. They were created by Italo Gismondi, who spent 36 years building a scale model of ancient Rome of the 4th century. The model is the highlight of the Museo della Civilta Romana in EUR.

The via Ostiense museum is open Tuesday – Sunday 9am-1pm. Even if you’re not interested in the exhibit, the admission is free and you get to climb around the ancient towers.

Adjacent to the Porta San Paolo is the Pyramid of Cestius, the 1st century Mausoleum of Gaius Cestius, the Imperial Banquet Manager/Party Planner to the Emperor Augustus. With his fortune he built himself a Pyramid Tomb, a tomb for one. He built it in 330 days.

Adjacent to the Porta San Paolo is the Pyramid of Cestius, the 1st century Mausoleum of Gaius Cestius, the Imperial Banquet Manager/Party Planner to the Emperor Augustus. With his fortune he built himself a Pyramid Tomb, a tomb for one. He built it in 330 days.

The reason the Pyramid is still with us is because it was incorporated into the Aurelian wall around 270 AD. This one was saved. There used to be another Pyramid near Castel Sant’Angelo but it ended up in the lime kilns.

The 119’ tall Carrara marble Pyramid of Cestius was restored in 2014 by the Yagi Tsusho LTD, the Japanese clothing company that also owns Moncler, one of Italy’s most prized fashions.

The Pyramid is open to the public on the 1st and 3rd Saturday of every month at 10:30am. It’s an accompanied tour. Reservations can be made by calling 06 5743193 or making them at the museum in the Via Ostiense Museum of the Porta San Paolo.

Visitors lower their bodies through a long (and low) passageway and finally emerge inside the burial chamber. The frescos on the wall are still in good condition. You can also see the tunnels dug in by the grave robbers.

Visitors lower their bodies through a long (and low) passageway and finally emerge inside the burial chamber. The frescos on the wall are still in good condition. You can also see the tunnels dug in by the grave robbers.

Porta Portese

From the Porta San Paolo, turn right and travel down the via Marmorata through the Testaccio neighborhood, a great place to stop for lunch.

From the Porta San Paolo, turn right and travel down the via Marmorata through the Testaccio neighborhood, a great place to stop for lunch.

Travel across the Ponte Sublicio (bridge) over the Tiber river and you’ll come to the next gate in the wall, the Porta Portese. Marmorata is for the marble that was unloaded there in ancient times.

The original Porta Portuensis was replaced by the current Porta Portese in 1644 as part of the Janiculum Wall of defense added by Pope Urban VIII (Barberini) as protection against Odoardo I Farnese, the Duke of Parma and his support of Venice, Tuscany and France.

The original Porta Portuensis was close to the Tiber River. It was here were transports were delivered from the Ports of Claudius and Trajan, the 1st and 2nd century Roman ports about 26 km down the river the Tiber. The modern location, now known as the Area Archeologica del Porto di Traiano is just behind the Fiumicino airport.

The original Porta Portuensis was close to the Tiber River. It was here were transports were delivered from the Ports of Claudius and Trajan, the 1st and 2nd century Roman ports about 26 km down the river the Tiber. The modern location, now known as the Area Archeologica del Porto di Traiano is just behind the Fiumicino airport.

In later years, Porta Portese led to the Porto di Ripa Grande, a warehouse port on the Tiber river near the Tiburtina island. Ripa Grande also included a large Arsenal for building military ships in the 16th century during the wars with the Ottoman Turks. The ramps going to Ripa Grande still exist just south of the Porta Portese and the Ponte Sublicio.

In 1798, the Arsenal was used by Napoleon to store stolen works of art. The Arsenal building still exists near the Porta Portese.

These days Porta Portese serves as the entrance to what many have called the largest open air flea market in Europe, possible the world. The first mile or so is filled with an endless canopy housewares and knockoff clothing. A couple of hours into the madness, the road takes a split and diverts to the actual flea market, filled with antiques (real and fake), memorabilia, jewelry, old records and tons of things you just have to buy even though you know they’ll end up in a junk drawer when you get home.

These days Porta Portese serves as the entrance to what many have called the largest open air flea market in Europe, possible the world. The first mile or so is filled with an endless canopy housewares and knockoff clothing. A couple of hours into the madness, the road takes a split and diverts to the actual flea market, filled with antiques (real and fake), memorabilia, jewelry, old records and tons of things you just have to buy even though you know they’ll end up in a junk drawer when you get home.

From Porta Portese we’ll head up towards the Gianicolo (Janiculum) Hill to the Porta San Pancrazio.

Porta San Pancrazio

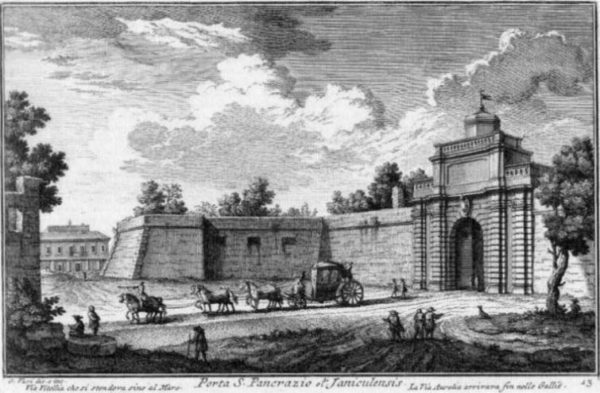

Porta San Pancrazio replace the Porta Aurelia built along the ancient via Aurelia that traveled from Rome towards Genoa and over to France. The original Porta Aurelia gate is long gone, so is the original location.

Porta San Pancrazio replace the Porta Aurelia built along the ancient via Aurelia that traveled from Rome towards Genoa and over to France. The original Porta Aurelia gate is long gone, so is the original location.

Vitiges and the Ostrogoths broke through the Porta Aurelia in 537 during the Gothic Wars of 535-554 but they were driven back out of the city walls by Belisarius and the Byzantine Army.

During the Middle Ages Porta Aurelia was renamed San Pancrazio when the catacomb of the Christian martyr, Saint Pancras was discovered nearby.

In the 17th, Pope Urban VIII had a new gate built. Since this was a total rebuild, he removed the Porta Aurelia and rebuilt the new Porta San Pancrazio somewhere nearby. This version of the Gate was blown up by the French while they were fighting off the Roman Republic forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi

In the 17th, Pope Urban VIII had a new gate built. Since this was a total rebuild, he removed the Porta Aurelia and rebuilt the new Porta San Pancrazio somewhere nearby. This version of the Gate was blown up by the French while they were fighting off the Roman Republic forces of Giuseppe Garibaldi

The new version, the one we see today, was built in 1854.

In 1870 the Roman Republic walked through the gate as part of the Italian Unification. This time they were led by General Nino Bixio, known to the Sicilians as the Butcher of Bronte from the brutal way he dealt with the bandit of Sicily near in Bronte, a town near Catania.

Porta Settimana

From here we’ll head back down the hill to the center of the Trastevere and to one of the more unusual Gates of the Aurelian Wall, the Porta Settimana.

From here we’ll head back down the hill to the center of the Trastevere and to one of the more unusual Gates of the Aurelian Wall, the Porta Settimana.

This version of Porta Settimana was built in 1498. It replaced one of the ancient Gates that led to the Tiber and onto the Ports of Claudius and Trajan.

Many think the name came from a monument to Septiminus Severus. The monument is long gone but some theories say it was at the entrance to the gardens owned by his son, Septiminus Geta, Emperor of Rome for a few months until he was killed by his brother Caracalla.

The 1498 gate was built by Pope Alexander VI (Borgia). What’s odd here is that the architectural merlons of the gate are in the swallowtail style of the Ghibbeline followers of the Holy Roman Emperor . The Papal Guelph merlons were squared off.

Rodrigo Borgia (Pope Alexander VI) was one of the most notoriously bad Popes, the subject of countless books, films and TV sagas. His design choice might have coincided with his alliance with the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximillian I in 1495 to keep France out of Italy.

The exterior side of the Porta Settimana marks the beginning of the via Lungara that leads to the Regina Coeli Prison of Rome.

Directly on the city side of the Gate, next to the gate is the house of Margherita Lutti, the Fornarina, the baker’s daughter and the love of the famous painter, Raphael Sanzio.

This is Raphael’s painting of ‘La Forniarina’. It is in the Palazzo Barberini, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome.

On her left arm is the band that reads Raphael Urbinas (Raphael was from the town of Urbino). It almost appears as an ‘I belong to Raphael’ armband.

From the Porta Settimana, follow the Tiber river north towards the Vatican. Continue north and cross over the Ponte Regina Margherita, the wife of King Umberto I, the 2nd King of Unified Italy and the namesake of the most famous pizza in the world, the Pizza Margherita.

Porta del Popolo

The Ponte Regina Margherita will lead you to Piazza del Popolo and the next gate in the wall, the Porta del Popolo, the gate opening into the grand Piazza del Popolo named for the 11th century church of Santa Maria del Popolo that sits up near the gate.

The older Porta Flaminia, named for the via Flaminia that traveled from Rome to Rimini on the Adriatic coast, was actually about 430 feet from current gate. By the 15th century, the old Porta Flaminia was in bad shape and mostly buried in centuries of river silt.

In the 10th century the old gate was renamed Porta San Valentino due to the close proximity to the Catacombs of Saint Valentine about 20 minutes north on the via Flaminia. During the Middle Ages, most of the gates were renamed for Saints. Some of the ancient one like San Sebastiano and San Paolo kept their saintly names. Others did not.

As the legend goes, The Emperor Nero was entombed near a grove of Poplar trees close to the current Piazza del Popolo. Adjacent to what is now the Porta del Popolo, there was once a nut tree filled with black crows where Nero’s ghost would feast alongside demons and witches.

In 1099, after many complaints of frightened Romans, Pope Paschal II ordered the tree to be burnt down and a chapel built in it’s place. Nero’s tomb was dug up and thrown into the Tiber River.

In 1475, a Jubilee year,Pope Sixtus IV (Della Rovere) enlarged the Chapel into the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo. He also had the new Porta del Popolo constructed about 430 ft from the old Porta Flaminia.

By the 16th century the Porta del Popolo became a major entry point for travelers from the north, so much so that less than 100 years after the Sixtus IV gate was built, Pope Pius IV (Medici) had it redone and enlarged to handle the traffic.

By the 16th century the Porta del Popolo became a major entry point for travelers from the north, so much so that less than 100 years after the Sixtus IV gate was built, Pope Pius IV (Medici) had it redone and enlarged to handle the traffic.

In 1562, Pius IV gave the commission to Michelangelo, but he was already working on the Porta Pia. He was also 87 years old. After Michelangelo’s refusal, Pius IV gave it to the Michelangelo copyist, Nanni di Baccio Bigio. He was a good copyist but a man Michelangelo never liked. Actually, Michelangelo never liked anyone.

The inner façade was designed by Gianlorenzo Bernini for Pope Alexander VII (Chigi) for the arrival of Queen Christina of Sweden in 1655. This was a big Catholic success story. Christina was a Protestant who converted to Catholicism and moved to Rome. That was the good story. Once she arrived, she became the source a scandals and wild parties.

The inner façade was designed by Gianlorenzo Bernini for Pope Alexander VII (Chigi) for the arrival of Queen Christina of Sweden in 1655. This was a big Catholic success story. Christina was a Protestant who converted to Catholicism and moved to Rome. That was the good story. Once she arrived, she became the source a scandals and wild parties.

A point of interest. On each side of the gate you can see the Papal shields of the two Popes who commissioned the work. On the exterior is the Papal Crest of the Medici, the 6 balls. The name Medici is associated with medicine and the balls might represent pills or cupping glasses. However, the Medici were not Doctors or Pharmacists. The number of balls changed over the years. In Florence, the major Medici city, you’ll see 5 balls on many of the shields. The 6 mountains under a star is the crest of the Chigi family and the Papal shield of Pope Alexander VII. The explanation might come from the hills surrounding Siena, the birthplace of the family wealth. As you walk through Rome you’ll many Papal shields. It’s fun to see which urban renewals were sponsored by which Popes.

In the 18th and 19th centuries the Porta del Popolo was the main entrance point for northern Europeans coming during the Age of Romanticism. Thousands of art lovers, writers, poets and painters came through this gate and rented rooms in the Piazza del Popolo or the nearby Piazza di Spagna. As traffic increased in the 19th century, the two side arches were added.

From here, we’ll take a short 20 minute stroll through the gardens of Rome’s Villa Borghese Park and end up at our last gate of the tour, the Porta Pinciana. If you walk along the via del Muro Torto you’ll see the retaining wall for an ancient garden (Horti Aciliorum) that predates the Aurelian Wall. Like many other pre-existing elements, it was incorporated into the wall in the Aurelian Wall of the 3rd century.

Porta Pinciana

The original Porta Pinciana from the 3rd century was just a ‘Posterula’, a postern or narrow gate for military access. It was enlarged to a proper fortified gate in the 5th century under the Emperor Honorius and defended by Belisarius against the Ostrogoths in 537.

There is another legend about the Porta Pinciana and Flavius Belisarius that circulated during the Middle Ages.

Emperor Justinian was always jealous of the Belisarius fame and according to the story, Justinian had Belisarius blinded and sent him to the Pincian Gate as a beggar for the remaining years of his life. The story is highly unbelievable. Belisarius and Justinian died within a week of each other and both were given fitting funerals. However, for a while during the Middle ages, the gate was known as the Porta Belisaria from the inscription (now lost) that read, ‘Date obolum Belisario’, give alms to Belisarius.

In the 9th century the Gate was closed and became known as the Porta Turata (Plugged gate) but it reopened during the reign of Pope Paul V (Borghese).

The Pope’s nephew, Scipione Borghese stored his art collection in the Villa Borghese, now one of the most popular museums in Rome. The Gate served as his personal entrance to the Villa.

The gate was closed off again when Napoleon advanced towards the Vatican in 1808 but by 187, it was repaired and reopened to the new communities springing up near the Borghese Park.

One last interesting anecdote about the Porta Pinciana. In 1974, Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped 820′ of the Aurelian Wall along the via Veneto up to the Porta Pinciana. The polypropylene fabric and dacron rope installation lasted 40 days. The reaction of Romans was mixed.

One last interesting anecdote about the Porta Pinciana. In 1974, Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapped 820′ of the Aurelian Wall along the via Veneto up to the Porta Pinciana. The polypropylene fabric and dacron rope installation lasted 40 days. The reaction of Romans was mixed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.