On January 14, 1506, a farmer named Felice da Fredis was digging up his vineyards in the Esquiline Hill and discovered a concealed chamber. Inside was one of the most fabled statues of all time.

In the 1st century AD, Pliny the Elder claimed it was the most amazing statue ever seen in ancient Rome, carved from a single block of stone by the three greatest sculptors of Rhodes; Hegesander, Polydorus and Athenodorus.

When Pope Julius II heard about the find he sent Michelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo to the excavation.

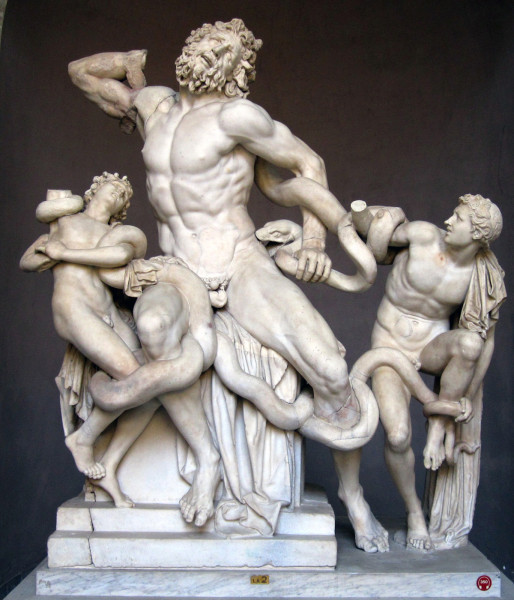

They returned to the Vatican and confirmed it was indeed the fabled statue of Laocoön and his sons.

Laocoön was the Trojan Priest who warned his people not to accept the Greek Trojan Horse, encouraging them to set it on fire to the false gift. The goddess Athena stopped him by sending serpents to devour Laocoön and his sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus.

The bronze statue above is a 1543 copy by Francesco Primaticcio. This is how the Laocoön appeared as it was found by Felice da Fredis. This bronze copy was on display in the Musee National du Chateau Fontainebleau, but in 1968 it was moved to the storage halls of the Louvre in Paris.

The statue was auctioned off and, of course, the winner was Pope Julius II who made it the centerpiece of his collection of ancient Roman art. In June of 1506, he placed the Laocoön off of the Belvedere Courtyard in a room currently known as the Octagonal Court of the Pio-Clementino Museum.

In August 1506, the collection in the Octagonal Court was opened to visiting guests to the Vatican. It was the birth of the Vatican Museums.

With the exception of 18 years when Napoleon took the great art of Rome to the Louvre in Paris, the Laocoön has been in the Octagonal Court for over 500 years,

When Napoleon was defeated in 1815, the repatriation of Italian art was underway. The Laocoön returned to the Vatican Museums in 1817.

When Felice da Fredis found the statue, it was in good condition, missing only a few segments of a serpent, the right arm of Laocoön, the right hand of one of the sons and the right arm of the other.

Around 1510, Pope Julius II decided to restore the missing pieces and gave the project to the Vatican architect, Donato Bramante.

Bramante held a contest to see who would come up with the best version of the arm restoration.

Michelangelo suggested that Laocoön’s missing arm should be bent back as if the Trojan priest was trying to rip the serpent off his back. He even sculpted a rough version of the arm to show Julius how it would look.

Raphael, who was the judge of the contest, favored the right arm extending out in a diagonal upward heroic pose, as if the Priest was telling the gods to stop their attack on him and his children.

The winner of the contest, Baccio Bandinelli, created a completely restored copy of the sculpture that was originally created as a gift for King Francois I of France.

However, Pope Clement VII like it too much to let it leave the country. He sent some odds and ends antiquities to Francois I and sent the Bandinelli Laocoön to Florence.

Pope Clement VII was originally Giulio dei Medici. The sculpture ended up going to the Palazzo Medici in Florence. It’s still in the Florence today, in the Uffizi Gallery.

Bandinelli’s arm of the Priest is not completely straight and does show some of the muscular tension of the Priest trying to pull the serpent from his body, but not as much as Michelangelo would have wanted.

In 1520, Bandinelli created a new arm for the Vatican Laocoön but either the arm was never quite right or it was damaged. It was never attached.

In 1532, Pope Clement VII asked Michelangelo to create a new (straight) arm for the statue, one that would look like Bandinelli’s copy.

Michelangelo refused. He neither wanted to copy Bandinelli (a man he hated) or create something wrong for the Laocoön. He still believed the arm should be bent.

The project was instead given to Michelangelo’s apprentice, Giovanni Montorsoli.

Clement VII was anticipating an arm that would resemble the Bandinelli restoration but the Montorsoli argued the arm should be stretched out in defiance.

It ended up looking more like John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever.

The image to the left is a copy of the Montorsoli arm made by Stefano Moderno in 1630.

Some say the Montorsoli arm was replaced by another in 1540. The new one, according to legend, was sculpted by Michelangelo.

The missing right hand and right arm of the two sons were created in the 18th century but they were removed in the early 1980’s.

In 1906 an archaeologist named Ludwig Pollak discovered a bent marble arm a short distance from where Felice da Fredis discovered the Laocoön in 1506.

Convinced it was the missing arm to the Laocoön, he presented it to the Vatican. They thanked him and put it into storage where it remained for 51 years.

In 1957, a Vatican curator decided Pollak’s arm was indeed the right piece and that Michelangelo was correct. The Montorsoli arm was removed and the Pollak arm was attached by art restorer, Filippo Magi.

Some say the straight arm is concealed behind the statue of the Laocoön. Others say it was sent to the storage rooms. I’ve also heard that the arm behind the statue is the roughly sculpted arm that Michelangelo created to prove his point to Bramante and Pope Julius in 1510.

I’ve tried to look behind the Laocoön many times. There is a well guarded museum rope closing off access to the back of the statue. The only thing I’ve seen so far is information about the legend.

This might have been the end of the story except that the new arm didn’t quite fit. A marble wedge was required to fill a gap. The new arm also seems to be a different color, more of a pinkish hue.

What archeologist/historians have surmised is that there were other versions of the statue which could have been copies of a 2nd century BC bronze.

The Laocoön in the Vatican Museum is an antiquity but it is not carved, as Pliny wrote, from one piece of stone.

Maybe the pinkish bent arm is from the Laocoön mentioned by Pliny the elder?

When Ludwig Pollak discovered the bent arm, he knew it was from the Loacoön but he also thought it might have been from a smaller version than the one in the Vatican.

What is ultimately wonderful is that you can see the story through the statue reproduction from 1510 till 1957. The pre 1957 straight arm or the post 1957 bent arm. There are copies in museums in Paris, London, Moscow and Italy and probably quite a few private collections.

A straight arm statue still welcomes you to the Vatican Museums on the ground floor as you approach the grand stairway.

You must be logged in to post a comment.