Along the via Agrippa:

Arles (Arelate), Barbegal Mill, Carpentras (Carpentoracte), Orange (Arausio), Vaison La Romaine (Vasio), Vienne (Viennensium)

The three great roads of the Roman Province were the via Domitia, the via Agrippa and the via Julia Augusta. The latter became known as the via Aurelia in the 3rd century when Aurelian (Lucius Domitius Aurelianus Augustus) became Rome’s 44th Emperor.

The three great roads of the Roman Province were the via Domitia, the via Agrippa and the via Julia Augusta. The latter became known as the via Aurelia in the 3rd century when Aurelian (Lucius Domitius Aurelianus Augustus) became Rome’s 44th Emperor.

There were other smaller roads connecting into the main three. Some of them were named, others were spurs of the route with the same name.

Of the three main Roman roads of the Roman Province, the via Agrippa was the northern route. By 16 BC, the via Agrippa traveled north from Arelate (Arles), Avennio (Avignon), Arausio (Orange), Vasio (Vaison la Romaine),Viennensium (Vienne), Lugdunum (Lyons), up towards Lake Geneva and onto Augusta Teverorum (Trier, Germany).

To find out about Ambrussum, Nîmes, Pont du Gard, Mas de Tourelles, Saint Rémy de Provence and Glanum, Les Baux de Provence and Les Trémaïés and Apt and Pont Julien, CLICK HERE for Provence along the via Domitia.

To find out more about sites along the via Julia Augusta (via Aurelia) CLICK HERE

Arles (Arelate)

Arles might be the most famous, and possibly the most important Roman city of the Province. It is also the city most associated with Julius Caesar.

During the civil War of Rome in 49BC, Massilia (Marseille) threw its allegiance with Pompey Magnus. Arelate supported Caesar. When Caesar emerged victorious, Massilia was punished. Arelate was rewarded. Massilia deteriorated. Arelate prospered.

After the war, Caesar renamed the settlement Colonia Julia Peterna Arelatensium Sextanorum and gave it to the veterans of his 6th Legion.

The city’s place on the Rhone River was in a perfect location for trade between northern and southern Gaul. It prospered from the river trade as well as its position, a confluence of the three major Roman roads through the Province.

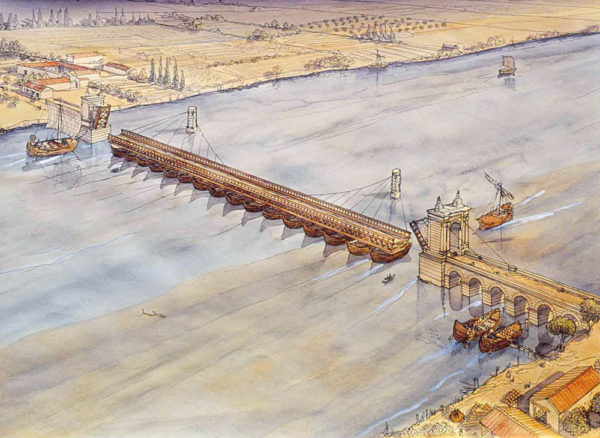

The (historically famous) pontoon bridge was built across the Rhone to connect to the via Domitia from Nimes to Marseille. The bridge hasn’t existed in many years. These days the way to Nimes is on the N113.

The (historically famous) pontoon bridge was built across the Rhone to connect to the via Domitia from Nimes to Marseille. The bridge hasn’t existed in many years. These days the way to Nimes is on the N113.

The route still goes across the Rhone, possibly in the same location as the pontoon bridge. It’s a 20 mile drive from Arles to Nîimes. It was a day’s march in the 1st century BC.

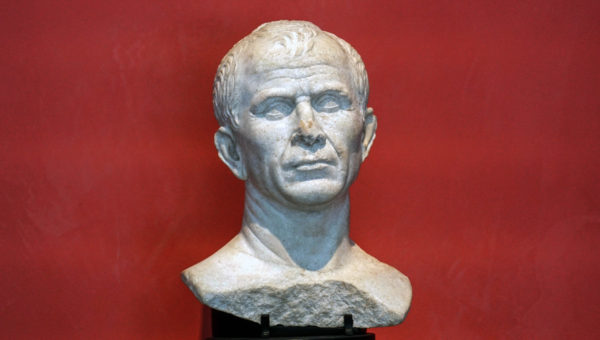

Although Caesar left Gaul in 50 BC, and died in 44 BC, he made another appearance in Arles in 2008.

Although Caesar left Gaul in 50 BC, and died in 44 BC, he made another appearance in Arles in 2008.

Archaeologists digging in a riverbed close to the city discovered this very realistic bust of Julius Caesar very possibly created during his lifetime. It is almost as if he sat for the portrait. Some speculation has it that the bust was tossed into the river after Caesar’s assassination because it would have been considered a politically sensitive possession, especially if Octavian, the future Emperor Augustus was defeated by Marc Antony.

The Caesar bust can be seen in the Musée Départemental de l’Arles Antique, an excellent museum that exhibits the history of the area dated from 2500 BC to the 6th century. The building opened in 1995. It’s one of the best Roman history museums in the world.

Aside from the bust of Julius Caesar, there are scale models of the Forum, the theater, amphitheater, pontoon bridge. circus and grain mills. There are statues, funerary objects and sarcophagi from the fabled Les Alyscamps. There are everyday agricultural tools, plumbing pipes, jewelry and household items. The ‘Piéce de Resistance’ of the collection is the Arles-Rhône 3, a 1st century Gallo-Roman barge.

The 102′ long flat bottom barge was discovered in 2004 and finally extracted from the bottom of the Rhone river in 2011. It was preserved in Switzerland and returned to the Arles museum in 2013. All moisture was removed from the 2000 year old wooden boards and replaced with polypropylene glycol. The result is amazing. The barge was discovered with its cargo of ingots and amphorae in tact. This photo is barely 1/2 of the barge.

The 102′ long flat bottom barge was discovered in 2004 and finally extracted from the bottom of the Rhone river in 2011. It was preserved in Switzerland and returned to the Arles museum in 2013. All moisture was removed from the 2000 year old wooden boards and replaced with polypropylene glycol. The result is amazing. The barge was discovered with its cargo of ingots and amphorae in tact. This photo is barely 1/2 of the barge.

Arles prospered till 235, the end of the Severan dynasty. In the 50 years between 235 and 285 there were 22 Emperors in Rome. By the time Diocletian took over in 284, the Empire was a mess. Constantine brought back some of the glory. It was from Arles in 312, where Constantine and his armies marched to Rome, defeated Maxentius and took over the empire.

In the year 308 Constantine built an Imperial Palace in Arles. Unfortunately all that’s left of the Palatial compound are what is now known as the Baths of Constantine.

In the year 308 Constantine built an Imperial Palace in Arles. Unfortunately all that’s left of the Palatial compound are what is now known as the Baths of Constantine.

Some say the Baths of Constantine were built to celebrate the birth of his son. Constantine II was born here in 317. It is a great example of the use of brick and stone popularized by the Romans. Stone for strength and brick to level the line for the next layer. This design was copied in many of the Moorish buildings that followed the Romans in the 8th century.

Inside the bath complex , the Apse of the semicircular dome is in great condition and really shows how this element became one the prototype of the Church. The apse of the bath and the apse of the church are pretty identical.

There are also good examples of hypocaust floor heating, the Roman system of heating a house or building by circulating hot air under the floor. The concrete and tile floor was raised on pilings of bricks. The hot air would circulate from the furnace through the room and out a flue in the roof.

There are also good examples of hypocaust floor heating, the Roman system of heating a house or building by circulating hot air under the floor. The concrete and tile floor was raised on pilings of bricks. The hot air would circulate from the furnace through the room and out a flue in the roof.

The Hotel d’Arlatan has a glass floor where you can see down 20 feet below to the ancient city of Augustus through to remains of Constantine’s Palace. Most of the Palace complex is still buried under a couple modern city blocks of Arles.

The Hotel d’Arlatan is closed right now (Oct 2016). The hotel is going through a renovation and any time you pull a permit in these historical buildings, the archeologists get a chance to unravel the past. It might not be good for hotel business but it’s great for history buffs. Hopefully Hotel d’Arlatan will reopen in a couple years with more access to the Constantine treasures.

The showpiece of Arles is the 446’ long x 358’ wide Flavian Amphitheater. It was built around 90 AD, 10 years after the completion of the Flavian Amphitheater (the Coliseum) in Rome. The Flavian Dynasty that ruled Rome between 69-96 AD built the amphitheaters in Rome, Arles, Nimes and Pula (Croatia). They have all survived.

The showpiece of Arles is the 446’ long x 358’ wide Flavian Amphitheater. It was built around 90 AD, 10 years after the completion of the Flavian Amphitheater (the Coliseum) in Rome. The Flavian Dynasty that ruled Rome between 69-96 AD built the amphitheaters in Rome, Arles, Nimes and Pula (Croatia). They have all survived.

The originally capacity of spectators was 21,000. The inscription of a 2nd century benefactor, C. Junius Priscus still appears on the podium wall separating the seats from the arena. Priscus also provided a gold statue of Neptune, four bronze statues and 2 days of games and banquets.

In the glory days of the Amphitheater there was a 2 meter (6’8”) clearance under the arena floor filled with trapdoor for surprise entrances of props and entertainers. Yes, Gladiators were entertainers. Although archeologists might be able to get down there, it is closed to the general public.

The reason this amazing amphitheater has survived is because it was transformed into a fortress city in the 5th century. Three of the original 4 towers of the fortress still remain. This wasn’t just a fortress, it was a mini city filled with hundreds of small houses and shops that weren’t cleared out till 1825.

Today it’s used mostly for bullfights during the Feria d’Arles in March and concerts during the summer months. The first Bullfight was held in 1830 to celebrate the victory and capture of Algiers, a victory the French would later regret.

Arles promotes both types of Bullfights, those in which the bull is killed and those where it is just taunted. And if you’re interested, there is a running of the bulls through the town before each Corridas.

The stairs going up to the top level are still intact and you can climb to the top of one of the remaining towers. The view from the top seating is the same view over the city as it was in the 1st century. Only the houses and streets have changed.

The stairs going up to the top level are still intact and you can climb to the top of one of the remaining towers. The view from the top seating is the same view over the city as it was in the 1st century. Only the houses and streets have changed.

The location of the Amphitheater is very close to The Hotel du Ville (Town Hall) and the Place du République, the center of modern Arles, also the center of the Ancient Arelate Forum.

Although very little of the Forum itself remains, the cellars and crypts that once stored merchandise for the shops in the Forum are still here. These porticoed crypts are known as the Cryptoporticus.

The Cryptoporticus is open to visitors. It’s a long U shaped cellar. The long arms of the U are close to 295’ long and the short arch of the U is 195’. It is sometimes used for temporary exhibitions but not during the rainy months. It’s gets wet down there.

The Cryptoporticus is open to visitors. It’s a long U shaped cellar. The long arms of the U are close to 295’ long and the short arch of the U is 195’. It is sometimes used for temporary exhibitions but not during the rainy months. It’s gets wet down there.

The Area around Place du République includes a few interesting museums; Museum of Pagan Art, Museum of Christian Art and the Arlatan Museum of everyday life in Arles through the centuries. The courtyard of the Arelate Museum is built around the apse of a Temple once connected to the Forum. However, the Arlatan Museum is closed till 2018.

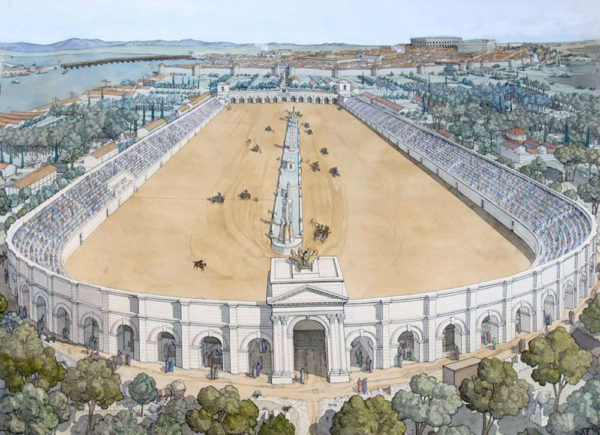

In front of the Hotel du Ville (in the Place de la République) sits the Obelisk of Arles. It once served as the center point of the spina to the Arles Circus. It was erected during the time of Constantine II in the 4th century. Recent examination have placed the granite obelisk origin from near Troy in Turkey. The Obelisk was moved to it’s current location in 1675 to celebrate King Louis XIV, the Sun King. The pedestal (not Roman) and fountain were added in the 19th century.

In front of the Hotel du Ville (in the Place de la République) sits the Obelisk of Arles. It once served as the center point of the spina to the Arles Circus. It was erected during the time of Constantine II in the 4th century. Recent examination have placed the granite obelisk origin from near Troy in Turkey. The Obelisk was moved to it’s current location in 1675 to celebrate King Louis XIV, the Sun King. The pedestal (not Roman) and fountain were added in the 19th century.

The Roman Theater was built on the Decumanus (now rue de la Calade) closer to the river. The Decumanus is one of the 2 main arteries of a Roman city. The Cardo mostly traveled north/south. The Decumanus went east/west.

The Roman Theater was built on the Decumanus (now rue de la Calade) closer to the river. The Decumanus is one of the 2 main arteries of a Roman city. The Cardo mostly traveled north/south. The Decumanus went east/west.

Usually the Decumanus traveled across a river or outside the city limits where the military fort was established. The current site of the Cardo is on rue Jean Jaurés, the street that passes through the Place de la Republique.

This is one of the few free standing ancient theaters in the world. Most of them were built along the slope of a hillside. The size is similar to the theater in Orange. Arles held 10,000, Orange held 9,000.

The theater was pillaged in the middle ages and mostly disappeared until the early 1900s when archeologist Jules Formigé rescued it from obscurity.

Many of the carved ornamentation is on display in the Musée Départemental de l’Arles Antique but he most famous piece, the Venus d’Arles was shipped off to the Louvre in Paris.

There was once a high scenic wall behind the stage but only 2 columns of the original wall remain. They’re referred to as the two widows. They were rebuilt during the excavation of Jules Formigé. There was a superstition during the Medieval times that this was a place of pagan sacrifices.

If the modern stage isn’t in place (it is set during the summer months for concerts and performances), look closely near the columns and you’ll see a ditch that once held the counterweights used to move the stage scenery. You’ll see some grooves in the stone where the tracks for the cable lines were set.

The entrance arches to the theater are still here. They provided the fortifications when the theater was transformed into a fortress in the middle ages. The tower over the entrance was added in the middle ages as part of the defense against the 8th century Saracen invasions.

The entrance arches to the theater are still here. They provided the fortifications when the theater was transformed into a fortress in the middle ages. The tower over the entrance was added in the middle ages as part of the defense against the 8th century Saracen invasions.

The tower is known as the Tower of Roland, named for the 8th century Knight who fought the Saracens under Charlemagne. Although the tower looks out of place, it was probably the only thing that saved the exterior wall from pillaging.

The Fortified walls that once protected the city are long gone. So are all the gates.

One of the original entrance gates near the Arena and along the Decumanus of the city is now known as the Gate of Augustus or the Redoute Gate (Fortress gate from Medieval times). All that remains of the original gate are the two round towers.

The Musée Départemental de l’Arles Antique is across the Canal d’Arles a Bouc. So are the remains of the Ancient Circus, the racetrack of Arelate. Its position along the Rhone must have been majestic in the 1st century. To support the massive structure some 25,000-30,000 tree log pilings were pounded into the ground for the substructure.

The Musée Départemental de l’Arles Antique is across the Canal d’Arles a Bouc. So are the remains of the Ancient Circus, the racetrack of Arelate. Its position along the Rhone must have been majestic in the 1st century. To support the massive structure some 25,000-30,000 tree log pilings were pounded into the ground for the substructure.

The site has been transformed into a garden with a design to show you the size of the Circus where 20,000 people cheered their favorite chariot teams.

Nearby the Circus, archeologists discovered a mausoleum they attribute to Constantine III (Flavius Claudius Constantinus), the Roman General in Britain who declared himself Emperor of Rome in 407 in an attempt to overthrow the Emperor Honorius. The coup failed. In 411 he was defeated and beheaded in Arles.

The Emperor Honorius made Arles the Imperial Administration of the Empire but in 471, but like many other Roman outposts, the city fell to the Visigoths.

As in all Roman cities, the dead were not allowed to be buried inside the city limits. The two main reasons were that you didn’t want the spirits of the dead haunting you and you definitely didn’t want decomposing remains infecting your gardens and drinking water.

Les Alyscamps is the Roman necropolis a short distance outside of Arles, actually it’s only a 15 minute walk from the Amphitheater.

Les Alyscamps is the Roman necropolis a short distance outside of Arles, actually it’s only a 15 minute walk from the Amphitheater.

The name is an Occitan derivative of the Latin Elisii Campi (Elysian Fields). Similar to the Appian Way in Rome, the road was adorned with monuments of the dead. Ancient Arelate produced the largest output of marble sarcophagi outside of Rome.

Even after the advent of Christianity, the necropolis remained a sacred place. It was the site of a Christian victory over the Saracens in the 8th century and the burial location of the most famous Christian of Arles, the 3rd century Saint Trophimus.

The Church of St Trophime, built between the 12th and 15th centuries, is one of the most famous churches in all of France. It was where the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa was crowned in 1178 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV in 1365. The main portal is one of the finest examples of Romanesque architecture.

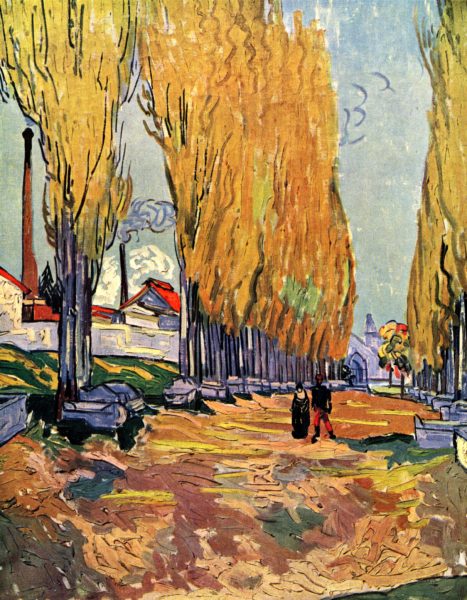

The monuments of Les Alyscamps were looted over the years and fallen into a romantic ruin, painted by Van Gogh and Gauguin in the late 19th century. There have been efforts to make some sort of historical order and these days there are rows of unused sarcophagi lining side of the road.

Barbegal Mill

On the outskirts of Arles, about 20 minutes by car, are the remains of the Aqueduct that fed Arles and the 3rd century Barbegal Mill.

On the outskirts of Arles, about 20 minutes by car, are the remains of the Aqueduct that fed Arles and the 3rd century Barbegal Mill.

The mill is one of the greatest achievements of the Roman engineering, probably built in the 2nd century during the time of the Emperor Trajan.

The excavation and rediscovery of the Barbegal Mill was carried out in 1936-38.

Water from an aqueduct powered water wheels that ground up to 4.5 tons of flour per day, enough to feed over 10,000 people.

That would have meant that everyone in Arelate would get (free) flour every 3 days.

This model of the mill is in the Musée Départemental Arles Antique.

The lower chambers of the mill have survived better than the ones up the hill because they were cut into the rock of the hill and they were harder to dismantle by foragers of building materials. The river that once flowed at the bottom of the mill is long gone. It’s now farmland.

You can still see how the aqueduct fed the mill through the cutaway in the rock leading to the hillside. These days it would be a simple explosion to blow a cavity into the stone. In the 1st century, the Romans drilled holes into the stone and drove metal wedges into the rock until it split. It could have taken weeks to carve this aqueduct passage.

You can still see how the aqueduct fed the mill through the cutaway in the rock leading to the hillside. These days it would be a simple explosion to blow a cavity into the stone. In the 1st century, the Romans drilled holes into the stone and drove metal wedges into the rock until it split. It could have taken weeks to carve this aqueduct passage.

Arles is very much associated with Vincent Van Gogh and most people come to this city more for Van Gogh than the Romans even though Van Gogh was here for just one year while the Romans were here for over 400 years.

In the one year Vincent Van Gogh lived here he made over 300 painting and drawings. The Foundation Vincent Van Gogh Arles was opened in 2014 after a major renovation of a 15th century home. It’s over 11,000 square feet over 2 floors.

Carpentras (Forum Neronis/Carpentoracte)

About 65 kilometers northwest of Arles is the small farming town of Carpentras (Forum Neronis/Carpentoracte).

Carpentras is a market town most famous for late winter Black truffles and Spring strawberries. During the first century it was a small farming community off a spur road of the via Agrippa.

Julius Caesar kept the Gallic name, Carpentoracte, when he built a small community here. The Emperor Tiberius (Tiberius Claudius Nero) changed the name to Forum Neronis around 16 AD.

Although most of the Roman city was destroyed in the 5th century, one piece of Roman antiquity remains, the 1st century AD Triumphal Arch.

The arch sits in the courtyard of the Palais de Justice on the Place d’Inguimbert. The Hall of Justice was once the Bishop’s Palace and the Bishop at the time thought it would be charming to have the arch in his courtyard. And so it was dismantled and erected here.

The arch sits in the courtyard of the Palais de Justice on the Place d’Inguimbert. The Hall of Justice was once the Bishop’s Palace and the Bishop at the time thought it would be charming to have the arch in his courtyard. And so it was dismantled and erected here.

Most of the arch is missing but what remains, the carved reliefs of German and Parthian prisoners on side panels, is worth the visit. The prisoners are immortalized in their defeat, weather worn and etched in time. The German is wearing a woolen coat. The Parthian prisoner wears the Phygian cap and tunic of Asia Minor.

There are a couple different theories about the origin of the arch. Some claim it was built during the time of Augustus to commemorate the Emperor’s victories in Germania (Germany) and Pontus (Turkey). Others claim is was built later during the time of Tiberius around 18 AD. Regardless of the origin date, it is the best example of Triumphal prisoners on a roman arch in all of Provence.

Orange (Arausio)

Orange sits about 40 miles north of Arles on the via Appia.

On October 6th 105 BC, this was the site of the worst Roman defeat in the history of the Empire. There were 80,000 Roman troops against 200,000 Teutones and Cimbri. According to early historians, the loss exceeded 80,000 Roman troops and 40,000 allies. Of course, ancient historians tended to exaggerate the casualties of war. It seems like every great Roman defeat or victory included a loss of at least 80,000.

According to Plutarch’s ‘Life of Marius’, the soil where the battle was fought became so fertile from the human remains it produced an overabundance of crops for many years.

Quintus Servilius Caepio, an elite Roman statesman and Consul returned home and was found guilty for the loss of his army. He was stripped of his citizenship and and exiled from Rome, not to live within 800 miles of the city. He was also fined 15,000 talents (about 825,000 pounds of gold) which he never paid. Quintus Servilius was the great grandfather of Marcus Junius Brutus, the most famous assassin of Julius Caesar.

The Roman Colony of Julia Firma Secundanorum Arausio was actually established during the time of Augustus between 36 BC and 19 AD. Some believe the local Gallic pronunciation of the name eventually morphed into something that sounded like the citrus fruit. By the 4th century the city was known as Orange. In 1713, Treaty of Utrecht gave the land to the Dutch House of Orange. It must have been convenient.

Arausio was another of the Celtic spring gods. The Celts built a settlement wherever they found a spring and named the location after one of their spring gods. The Romans in many cases, kept the names. It’s kind of like the Europeans wiping out the indigenous Americans and then naming towns and streets with the indigenous names.

Augustus awarded the Colony of Arausio to the veterans of the Legion II Gallica. Land was a common reward for service in the military. The 6th Legion was given land in Arles, the 10th Legion in Narbo, the 8th in Frejus and the 7th in Béziers.

Arausio was a sizeable Colony protected a 3.5 kilometer fortress wall. The Avenue de L’arc and the Rue Victor Hugo follow the ancient Cardo, the north-south avenue, and the Rue de la République in the east-west Decumanus.

Arausio became one of the most successful trading ports on the Rhone River, mostly built in the 1st century BC. Most likely, all the Augustan architecture was built by Marcus Agrippa.

The main entrance to the Colony was from the north on the via Agrippa. This 72’ high and 69’ wide Triumphal Arch is the largest in the Province, a great arch carved with victory illustrations of the 2nd legion.

The main entrance to the Colony was from the north on the via Agrippa. This 72’ high and 69’ wide Triumphal Arch is the largest in the Province, a great arch carved with victory illustrations of the 2nd legion.

The origin of the arch has confused historians for years with origin dates ranging from 16BC to 35 AD.

We know it is a triumph to the glory of the 2nd Legion, one of the Legions of Augustus. It is very possible the arch was first built in 16AD and then rebuilt many times and consequently rededicated to successive emperors.

The arch is in such good condition because it was incorporated into the fortress guarding the northern approach of the city. Four levels of the monument have survived. It was once capped with statues. Many historians believe it was once painted in vivid colors.

The panels of the arch are decorated with the images of the spoils of war, armor, swords, battle shields and even prisoners sold into slavery. If you look at the center top, the second attic over the pediment, you’ll be able to make out a soldier carrying a shield with a carved image of a Capricorn. This was the symbol of the 2nd Legion.

You can also tell who is who in the prisoner count. The pants wearing Gauls are bare chested. The Germans wear leather caps.

You can also tell who is who in the prisoner count. The pants wearing Gauls are bare chested. The Germans wear leather caps.

The Theater of Orange, the best example of a Roman theater in all of Europe, once had a capacity of 9,000 people. These days it hold barely 900 for summer performances.

There are some great Roman Theaters in the world; Basra and Palmyra in Syria, Aspendos in Turkey, Sabratha in Libya, but Orange is the best example in the western world. Most likely it was built during the time of Augustus at the same time as the Theater in Arles. They are both roughly the same size.

There are some great Roman Theaters in the world; Basra and Palmyra in Syria, Aspendos in Turkey, Sabratha in Libya, but Orange is the best example in the western world. Most likely it was built during the time of Augustus at the same time as the Theater in Arles. They are both roughly the same size.

The niches in the wall once held statues of gods and famous Romans. Now there is only one statue, the large (twice human scale) statue of Augustus. He was recreated from bits and pieces strewn across the excavation in the 1930s. After he was put back together, his hand was raised to welcome the crowd.

As with most Roman theaters, the cavea (seating tiers) is carved into a hillside. The cavea was built with three tiers. The lower tiers were entered from side entrances at the bottom. The top tiers had access up exterior stairs through entrances into the cavea. Many of these barrel vaulted entrances still exist and are still in use.

In the theater of Orange, the height of the cavea was equal to the height of the stage wall. The entire structure was once surrounded with columns that supported a roof to shade the guests.

The stage was raised for better viewing with the orchestra just in front of the stage for high ranking officials. In Greek times, the orchestra was reserved for the Greek chorus.

From the street outside the theater, the 120′ tall wall looks almost the same as it did over 2000 years ago. It was protected over the years because, like many of the larger Roman buildings throughout Provence, the theater was made into a fortress. Some of the houses built inside of the theater weren’t cleared out till the mid 19th century.

From the street outside the theater, the 120′ tall wall looks almost the same as it did over 2000 years ago. It was protected over the years because, like many of the larger Roman buildings throughout Provence, the theater was made into a fortress. Some of the houses built inside of the theater weren’t cleared out till the mid 19th century.

Every summer from July to August, the Theater hosts a variety of jazz, classical music and Opera performances. http://www.choregies.fr/

The price of admission includes the museum which does have a few very good masks from the excavation.

Vaison la Romaine (Vasio)

Vasio (Vaison la Romaine) is basically a recreation of a Roman town. It was excavated between 1907-1955, a personal passion of the Catholic Priest and Archaeologist, Joseph Sautel. He died in 1955 while still digging the site. It is the largest area of Roman remains in all of France, a size that has given the site the dubious title of the Pompeii of Provence.

To get an idea of what the town once looked like, this site by Archaeologist and Illustrator Jean-Claude Golvin will explain much more than I can.

In the two excavated areas you can see a once beautiful town with paved streets, buildings and shops, toilets and sewers. This was a wealthy town. One of the houses (the House of the Silver Bust) spreads across an area of 55,000 square feet. The name comes from a metal bust of the (presumed) owner that was found here during the excavation. It’s now displayed in the Vaison la Romaine Museum.

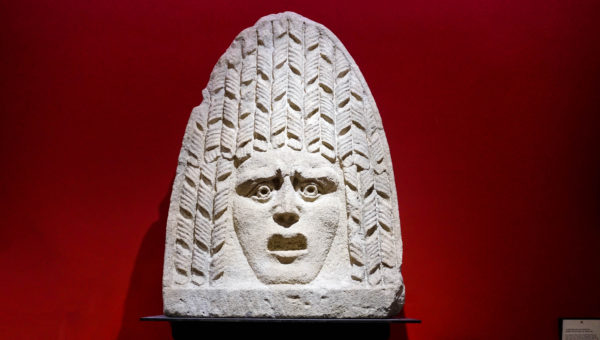

Most of the impressive pieces were removed from the ruins and placed into the museum, including a mosaic floor from the House of the Peacock, theater masks excavated near the hillside theater, plumbing pipes and water heaters and statues of Emperors; Claudius with draped toga over bare upper figure, Domitian with his commander in chief breastplate and Hadrian in a heroic pose wearing a beard.

Hadrian was the first Emperor to wear a beard in the Greek style. He set a style precedent that lasted for close to 100 years before a clean shaven teenage emperor Elagabalus came in 218 AD.

Hadrian is placed near a statue of his wife, Vibia Sabina, the niece of the Emperor Trajan who was also the adopted father of Hadrian. Roman blood lines can be confusing. It was a childless and basically unhappy marriage. He was 24 and she was 20 when they married 17 years before he became Emperor. Hadrian preferred travel,architecture and young men to her company. After she complained, he distanced himself even further from her, even removing her friends from the royal court. Rumor has it that she went on to have an affair with the Roman historian, Suetonius, the author of the wonderful book ‘The Twelve Caesars‘.

The Vasio theater once held 6,000 people on 32 tiers along the slopes of Mount Ventoux. Although the theater was built during the time of Augustus, it was renovated during the time of Hadrian around 120 AD and then again in 1911 by Joseph Sautel. In honor of his participation in the 120 AD renovation, a naked statue of the Emperor Hadrian (now in the Vaison museum) was placed in the theater. Although most of the theater has been rebuilt, the columns that decorate the top of the cavea seating are original. At one point the entire top of the cavea was a beautiful colonnade.

The Vasio theater once held 6,000 people on 32 tiers along the slopes of Mount Ventoux. Although the theater was built during the time of Augustus, it was renovated during the time of Hadrian around 120 AD and then again in 1911 by Joseph Sautel. In honor of his participation in the 120 AD renovation, a naked statue of the Emperor Hadrian (now in the Vaison museum) was placed in the theater. Although most of the theater has been rebuilt, the columns that decorate the top of the cavea seating are original. At one point the entire top of the cavea was a beautiful colonnade.

These days the audience looks down to the stage but in place of the theater back wall they now look at the traffic roar by on a very busy avenue. If it’s a good performance you might not notice the distraction.

There is an annual dance festival at the Theater every July. The Festival began in 1996 and since then it has attracted many important choreographers and dance companies.

Vaison La Romaine has two cities, the ancient Roman city below and the medieval city above the Ouvèze river. They are connected by a 1st century Roman bridge.

Vaison La Romaine has two cities, the ancient Roman city below and the medieval city above the Ouvèze river. They are connected by a 1st century Roman bridge.

This 56’ long bridge has withstood the centuries. It still handles the car traffic across the river.

The bronze clamps holding the stones together have withstood 2000 years. There was some damage during World War II but not enough the bring the bridge down.

In 1992, when the Ouvéze River flooded the town of Vaison La Romaine, the only bridge the remained upright was the Roman bridge. All other river crossing were torn down in the flood.

(Colonia Julia Florentia Viennensium) Vienne

Most of this tour of Roman Provence stays in the south of France. The Via Agrippa travels north to Lyons and further.

One of the major Roman settlements in the northern part of the road is the city of Vienne, just south of Lyon was settled during the time of Julius Caesar in Gaul. It is not in Provence but it’s only a 2hr drive north of Avignon in the Rhone Alps.

Settled at a key bend in the Rhone river, Vienne was the most prosperous city in the Roman Province in the in the 1st and 2nd centuries. It was the natural crossing point of the river if you wanted to avoid the marshes both north and south. The bridge that once made the crossing is gone.

Vienne became Roman property in 120 BC in the first wave of Roman colonization when the General Fabius Maximus conquered the Allobroges tribe and created the first settlement. When the Allobroges took the town back in a revolt of 61 BC, the Romans fled north and founded the town of Lugdunum (Lyons). Julius Caesar eventually took back the town and rebuilt it. Augustus granted all the citizens Roman citizenship.

Both Vienne (Viennensium) and Lyons (Lugdunum) prospered and by 69 AD the rivalry was so bitter, the people of Lugdunum petitioned the Emperor Vitellius in Rome to destroy Vienne. Since Vitellius was Emperor for barely 8 months, he never had time to respond to the request.

The Temple of Augustus and Livia was erected during Augustus’ first visit to the Province, around the same time as the temple in Nîmes. Consequent reconstructions were made during the time of Emperor Tiberius or possibly Emperor Claudius in the 1st century AD.

The Temple of Augustus and Livia was erected during Augustus’ first visit to the Province, around the same time as the temple in Nîmes. Consequent reconstructions were made during the time of Emperor Tiberius or possibly Emperor Claudius in the 1st century AD.

The condition of the Temple is once again thanks to its transformation to a Church. After the French Revolution it was turned into a Jacobin Reign of Terror club that followed the Revolution.

Thanks to the 19th century archeologist, Prosper Mérimée, it was restored to it’s historical temple appearance in the mid 19th century. It is not in as good condition as the Maison Carée of Nimes but it’s a very good example of 1st century Roman architecture.

The 2nd century small pyramid sitting on top of a mini triumphal arch is known as the Plan de L’Aiguille. It stood at the center of the spina of the Circus, a long series of fountains and turning posts to keep score of the turns around the racetrack.

The 2nd century small pyramid sitting on top of a mini triumphal arch is known as the Plan de L’Aiguille. It stood at the center of the spina of the Circus, a long series of fountains and turning posts to keep score of the turns around the racetrack.

It’s still pretty impressive, rising up 51’ over the arch. A bizarre legend has that it was built by Pontius Pilate as his tomb.

The Garden of Cybele park was built from the ancient Roman Forum. The site was excavated by French Architect, Jules Formigé and others between 1945-1968 and labeled as a center for the cult of Cybele , the earth goddess and mother of all gods.

The 40 AD Roman theater , also excavated by Jules Formigé is the second largest theater in France, 46 tiers accommodating 13,500 people. It sits on the slope of Mont Pipet. Although not much is preserved of the grand entrances or the stage wall, the restored cavea (tiers of seats) still accommodate the annual theater and the Vienne Jazz festival that since it’s inception in 1981 has brought in names like Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Ella Fitzgerald, Chuck Berry and Ike Turner. http://jazzfestival2016.com/events/jazz-festivals-in-europe/jazz-a-vienne/

Vienne was actually a twin city built on both sides of the Rhone river. One side was Vienne and the other is now called Saint Roman-en-Gal, an archeological dig uncovered in 1967 when a high school was being built. The site is still under excavation. The archeological site includes a large villa, baths, merchant stalls, gardens, an ancient vineyard. Inside the museum is a full scale model of a cargo ship that once sailed up the Rhone from Arles to Vienne and Lyon.

Other interesting sites along the via Agrippa include the archeological site of Alba La Romaine and the bas relief carving of a Mithraic bull in Bourg-Saint-Andeol.

If you wish to find more information on the Roman Province I highly recommend the book ‘The Roman Remains of Southern France’ by James Bromwich. The book is out of print but there are still copies available. Another great resource is The Roman Provence Guide by Edwin Mullins. Much of the information used in this article was provided in these two books.

The Provincia of Rome was looted, destroyed, repurposed and thankfully put back together thanks to Prosper Mérimée when he was the Chief Inspector of Historic Monuments in the mid 19th century.

Mérimée is most noted as the author of the novella Carmen that became the Bizet’s Opera of the same name, however, he did a lot more than giving the world the story of the gypsy Carmen. Mérimée saved the UNESCO city of Carcassonne from destruction and saved so many of the Roman antiquities in France. We owe him our deepest thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.