Along the via Domitia:

Ambrussum – Nîmes – Pont du Gard – Mas de Tourelles – Saint Rémy de Provence and Glanum – Les Baux de Provence and Les Trémaïés – Apt and Pont Julien

La Provincia di Roma, as it was known during the Roman empire, actually extends past the current borders of Provence. Redistricting over the years has pushed Nîmes, Ambrussum and Pont Du Gard into the Languedoc, separated Vienne and Lyons to the Rhone Alps and pushed Fréjus, Nice and Antibes in the Côtes d’Azur. And so it goes. The geographical border of the Province might be different but when you come here to search for the Roman civilization from the 1st century BC to the 4th century AD, borders don’t really mean that much.

La Provincia di Roma, as it was known during the Roman empire, actually extends past the current borders of Provence. Redistricting over the years has pushed Nîmes, Ambrussum and Pont Du Gard into the Languedoc, separated Vienne and Lyons to the Rhone Alps and pushed Fréjus, Nice and Antibes in the Côtes d’Azur. And so it goes. The geographical border of the Province might be different but when you come here to search for the Roman civilization from the 1st century BC to the 4th century AD, borders don’t really mean that much.

This article focuses on Roman sites along the via Domitia.

To find out more about Arles, the Barbegal Mill, Carpentras, Orange, Vaison La Romaine and Vienne, CLICK HERE for Provence along the via Agrippa.

To find out more about sites along the via Julia Augusta (via Aurelia) CLICK HERE

In 125 BC France was known as La Provincia Gallia Transalpina (the Province of Gaul across the Alps). The Roman Empire traded with the Greek port of Massilia (Marseille) since before the Punic Wars with Carthage (264 BC-146 BC). By the year 146 BC, Carthage was no more and Rome reigned supreme across the Mediterranean.

The whole thing started in 125 BC when Massilia was attacked by a confederation of northern Celtic tribes known as the Saylens. Massilia was a wealthy trading port but they barely had a military defense against the invading Saylens. They called on Rome for help. Rome responded with troops and put down the invasion.

Calling Rome for help might have seemed like a good idea at the time but once you invite the Roman Empire into your house, they never leave. Instead of returning home, they colonized. From the original encampment of Aquae Sextius (Aix en Provence) they expanded and built their own port city, the Colonia Narbo Martius, modern day Narbonne.

The new colony was called Gallia Narbonensis. Their governor was Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, a man who would eventually become more famous for the via Domitia, the road he sponsored and named after himself.

The wealthy and powerful Ahenobarbus (red beard) family was a major player in the development of the 1st century Rome. They were on the wrong side of the war against Julius Caesar but on the right side when they allied with Augustus Caesar. Eventually they married into the Imperial family but it all ended with Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus who changed his name to Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, better known as the Emperor Nero.

Roman Roads of the Province

We are indebted to the Romans for so much.

We are indebted to the Romans for so much.

They gave us aqueducts, sewers, concrete, indoor plumbing, indoor heating, engineering, large scale entertainment, written history, the first bound (codex) books, legal systems still used today, the 3 course meal, social welfare, the census, pay toilets, the calendar, medical advancements (field surgery and Cesarean births to name a couple) and Christmas.

They also gave us roads, over 50,000 miles of them across the Empire.

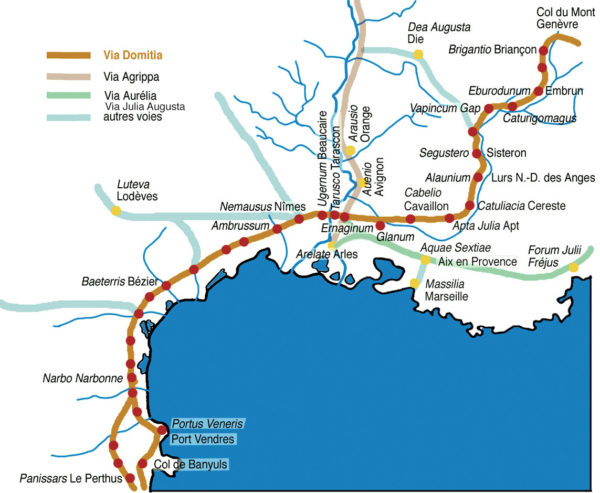

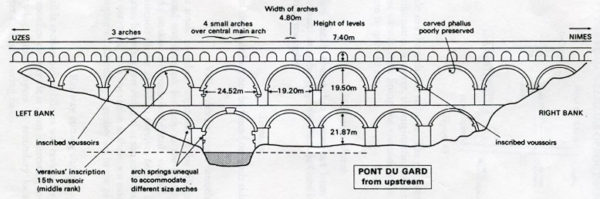

The three great roads of the Roman Province were the via Domitia, the via Agrippa and the via Julia Augusta. The latter was incorporated into the older via Aurelia in the 3rd century. The Emperor who changed the name, coincidently, was Emperor Aurelian.

The three great roads of the Roman Province were the via Domitia, the via Agrippa and the via Julia Augusta. The latter was incorporated into the older via Aurelia in the 3rd century. The Emperor who changed the name, coincidently, was Emperor Aurelian.

There were other smaller roads connecting into the main three. Some of them were named, others were spurs of the route with the same name.

They were built by the military for the military. They supported armies, wagon loads of military equipment and supplies.

The roads were constructed with three layers of foundation, ample drainage and every 17 miles there was a rest stop with food, medical support, fresh horses and shelter.

Milestones, Roman road markers calculated the distance to major settlements along the road and, of course, how many miles back to Rome.

Milestones, Roman road markers calculated the distance to major settlements along the road and, of course, how many miles back to Rome.

By 10 BC, the Roman Province spread west across the Languedoc and Roussillon, north through the Rhone Alps to Lake Geneva and east to the Maritime Alps and the Côte d’Azur. In just 100 years, Rome built cities, aqueducts, bridges and over 3,000 miles of stone roads in the Province. Most of them have been destroyed or paved over. Some have been replaced by highways and rural roads.

Along the via Domitia

The via Domitia traveled north through Narbonne and Nimes and then turned northeast through Arles, Les Baux de Provence, Saint Rémy de Provence, Caviallon, Apt, Gap, Briançon, turning into the High Alps of France and onto Turin, Italy.

The via Domitia traveled north through Narbonne and Nimes and then turned northeast through Arles, Les Baux de Provence, Saint Rémy de Provence, Caviallon, Apt, Gap, Briançon, turning into the High Alps of France and onto Turin, Italy.

The via Domitia is the oldest road in France. Some parts of the road are much older than Domitius Ahenabarbus’ namesake.

It was the ancient path used by Hercules in his 10th labor, retrieving the cattle of Geryon from Erytheia (Cadiz, Spain) and bringing them back to Mycenaea (Peloponnese, Greece).

It was the ancient path used by Hercules in his 10th labor, retrieving the cattle of Geryon from Erytheia (Cadiz, Spain) and bringing them back to Mycenaea (Peloponnese, Greece).

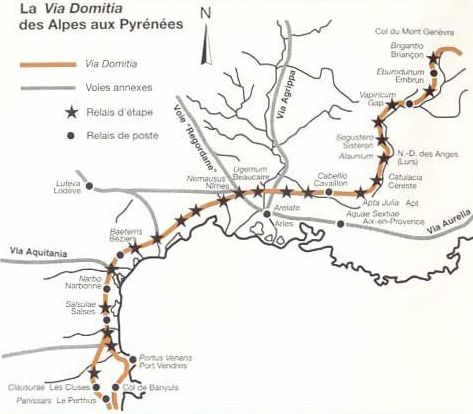

It was the road used by Hannibal and his army of 50,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry and 37 elephants when in 218 BC they marched up the coast of Spain and across the Pyrenees into Italy during the 2nd Punic War.

It was the road used by Hannibal and his army of 50,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry and 37 elephants when in 218 BC they marched up the coast of Spain and across the Pyrenees into Italy during the 2nd Punic War.

Although Narbo Martius (Narbonne) was the original Colonial capital of the Province, there is really nothing left of the ancient Roman city.

The only visible remnant of the road named for the city’s founder is a small exposed archeological excavation near the Hotel du Ville (Town Hall).

Ambrussum

About 34 kilometers southwest of Nimes, close to the modern town of Lunel, is the ancient farming community of Ambrussum, . This is a good place to dip your toes into the via Domitia for a relaxing 1.5 hr walk.

From the Museum and visitor center, the ancient road opens up to a 2.3km walk along the ancient stones. The centuries of wagon cartwheels have permanently embedded themselves in the stones.

Towards the beginning of the hike you’ll come to the remains of the 1st century Pont Ambroix, the bridge that once crossed the Vidourle River. Only one arch of the Pont Ambroix remains. It once had 11 arches with a 21.5′ carriageway, an ancient 2 lane bridge.

Two arches remained up to the 1940’s. Now there is only one. It’s hard to imagine this peaceful small river taking down this massive bridge, but it did.

The 19th century French realist painter, Gustave Courbet painted the bridge when it had two arches in 1857.

From there it’s an easy hike up to the ruins of the Oppidum (fortress) that once protected this small community.

From there it’s an easy hike up to the ruins of the Oppidum (fortress) that once protected this small community.

Nîmes (Nemausus)

In 27 BC, Octavian, the adopted son of Julius Caesar was proclaimed Rome’s first Emperor Augustus, the most revered. In honor of his new title, he decided to tour Gaul.

The Empire was a bit unstable after the recent Civil War between Octavian/Augustus and Mark Anthony. Augustus appointed his best friend, military genius, civic planner and son-in-law, Marcus Agrippa as Governor of the Roman Province. Agrippa was possibly the greatest civil builder of the 1st century. His hand stretches from Rome to Greece to Syria, Judea and Spain. The city of Nemausus (modern day Nîmes) was one of his greatest achievements in the Province of Gallia Narbonnensis.

At it’s height, the population of over 60,000 was protected by a 3.7 mile fortress wall with 14 towers. Only two gates of the original fortifications remain today.

The Porta Augusta, one of the 2 remaining gates, has 2 large arches for carriages and 2 smaller arches for foot traffic. The exterior of the gate is now below the street level but you can still see the grooves where the portcullis gate would have closed all access. The gate was the primary northern entrances along the via Domitia.

The Porta Augusta, one of the 2 remaining gates, has 2 large arches for carriages and 2 smaller arches for foot traffic. The exterior of the gate is now below the street level but you can still see the grooves where the portcullis gate would have closed all access. The gate was the primary northern entrances along the via Domitia.

The city placed a statue of Augustus inside the gate. It is a copy of the famous Prima Porta statue in the Vatican of Rome.

The single arch Porte de France opened to the southwest access of the via Domitia, back towards Narbonne. It is much smaller than the grand Augustan Gate but it is possible this arch is all that remains from a larger gate. It is also possible this was just a smaller arch used for merchants.

The single arch Porte de France opened to the southwest access of the via Domitia, back towards Narbonne. It is much smaller than the grand Augustan Gate but it is possible this arch is all that remains from a larger gate. It is also possible this was just a smaller arch used for merchants.

Most of the fortified walls around the city are gone. The few remaining pieces are barely 6’ tall. However, one of the towers still remains.

The Tour Magne has been restored (or rebuilt) at least a few times, the last one was very recent. It’s big, over 100’ tall. It could have been a lookout tower or a beacon for travelers coming to the city.

The Tour Magne has been restored (or rebuilt) at least a few times, the last one was very recent. It’s big, over 100’ tall. It could have been a lookout tower or a beacon for travelers coming to the city.

Since the tower was built during the Pax Romana, a 200 year period of peace in the Empire, it’s most likely the tower was a monument of civic pride, showing off the location of the city to travelers in the distance.

In the 17th century Nostradomus predicted there was a vast treasure buried inside. His prediction turned out wrong. Unfortunately, it almost destroyed the tower. The Tour Magne is actually a tower inside a tower. The original one is about half the height of the exterior tower. These days a staircase is built in the center of the tower and it’s open from 9:30am till 7:30pm during the tourist season. The hours are shorter the rest of the year.

It’s a good climb and the views are spectacular but it’s not for the faint of heart who suffer from vertigo.

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa built what is now known as the Maison Carrée in 19 BC as a temple to the cult of Augustus. Augustus had adopted the children of Agrippa and Julia the Elder (his daughter) with hopes that they would inherit the rule of the empire. Unfortunately, they died 10 years before the death of Augustus.

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa built what is now known as the Maison Carrée in 19 BC as a temple to the cult of Augustus. Augustus had adopted the children of Agrippa and Julia the Elder (his daughter) with hopes that they would inherit the rule of the empire. Unfortunately, they died 10 years before the death of Augustus.

Lucius died in Massilia (Marseilles) in 2 AD at age 17. Gaius died in Armenia in 4 AD at age 24. Around this time, the Temple was rededicated to the two princes.

The inscription on the Temple read: C CAESARI AUGUSTI FI COS L CAESARI AUGUSTI F COS DESIGNATO PRINCIPIBUS JUVENTUTIS

Caius Caesar son of Augustus, Lucius Caesar son of Augustus, designated Princes of the youth.

Maison Carrée is the most perfect Greek/Roman temple in existence. Although the Church destroyed many Roman temples for building materials, this one was saved and converted into a church. It was turned into a museum in 1821. It was just restored again in 2013.

The temple sat in the Forum of Nîmes, actually it sat above the Forum. The 15 steps leading from the Forum to the temple floor were specially designed so that the visitor would start and stop on the same foot.

Another interesting feature is that the length of the temple has a slight convex curve in the bottom of the columns created to correct the optical illusion of straightness. Normally a straight run of columns would have the optical illusion of bulging outward. By adding the bulge in the column it fixes the optical illusion, or creates another one that is more appealing. It’s an architectural idea known as entasis that goes back to the ancient Greeks and Egyptians. The architectural style is very prominent in the columns of the Parthenon in Athens.

Although the French refer to the temple as the Maison Carée (The Square House), it’s actually a rectangle. It’s comprised of a rebuilt open porch supported by Corinthian columns and a cella (inner sanctum) reserved for the deity. The statue of Augustus that once filled the inner sanctum is long gone, it was replaced with the headless statue of Venus discovered in 1873 known as the Venus of Nîmes. She was discovered in 300 pieces, reassembled and then moved to the Archeological museum which is now closed. The new one, built across the square from the Nimes Arena, won’t be open until 2018.

The cella is now a film theater where a film is shown on the founding of Nimes. It’s a very French/Nimes version of local history but it has good production value and even if the facts might be mangled a bit, it’s still fun to watch.

One more thing to note here. Next door to the Maison Carrée is the 1993 modern glass museum by the British Architect, Norman Foster. It’s called the Carrée d’Art. The relationship of the 1st century and 20th century architectural styles is probably something Agrippa would have appreciated.

One more thing to note here. Next door to the Maison Carrée is the 1993 modern glass museum by the British Architect, Norman Foster. It’s called the Carrée d’Art. The relationship of the 1st century and 20th century architectural styles is probably something Agrippa would have appreciated.

The Romans (and the Volcae Arecomici who predated them here) believed a natural spring to be the home of sacred water gods and whenever they built a colony near one of these springs, they were obliged to build an altar of worship.

The Nymphaeum of Nemausus (Nimes) was most likely built by Marcus Agrippa and consequently dedicated to the cult of Augustus. The name of the Celtic water god was Nemausus, which became the Roman name for the Colony.

Nymphaea were places of worship, public celebration and weddings. Celts and Romans would toss coins, jewelry or other gifts into the sacred pools of 1st century Nymphaeum as tokens of good fortune. People are still doing it. Fountains all over the world are forever filled with wishing coins.

Nymphaea were places of worship, public celebration and weddings. Celts and Romans would toss coins, jewelry or other gifts into the sacred pools of 1st century Nymphaeum as tokens of good fortune. People are still doing it. Fountains all over the world are forever filled with wishing coins.

This particular Nymphaeum was known for it’s healing waters. The fountain sanctuary was set up as a hospital, similar to a Greek Aesclepion, where patients would go to sleep and their dreams would provide the information to the doctors for their cures. By the way, many of these cures were highly successful.

The Jardins de la Fontaine now covers the site of the ancient spring of the Nymphaeum. It has since 1745. It’s a beautiful park filled with statues and balustrade evocative of the ancient Romans. The water from the ancient spring is still here.

The Temple of Diana in the Jardins de la Fontaine is another in the series of Temples renamed to honor the Moon goddess, even though there is no evidence relating the structure to Diana, nor is there any evidence that it was a temple.

The Temple of Diana in the Jardins de la Fontaine is another in the series of Temples renamed to honor the Moon goddess, even though there is no evidence relating the structure to Diana, nor is there any evidence that it was a temple.

The (so called) Temple of Diana was probably constructed at the time of Augustus and Marcus Agrippa and then renovated in the early 2nd century by Hadrian as part of a bath complex or library.

Many historians think it was a library based on the design of the Celsus library at Ephesus in Turkey.

In the 10th century it was transformed into a convent for the Nuns of San Salvador but during the wars of Catholics vs Protestants, the structure was badly damaged by the Catholics when they destroyed it in order to keep it out of the hands of the Protestants.

These days it’s just part of the landscape of the park and a hangout for the Nîmes youth. In any other part of the world, there would be an entrance gate and paid admission to enter.

The Nimes Amphitheater, like most ancient Roman Arenas, is the most impressive structure of the 1st century city. It might be the best preserved Roman amphitheater in the world.

The Nimes Amphitheater, like most ancient Roman Arenas, is the most impressive structure of the 1st century city. It might be the best preserved Roman amphitheater in the world.

Built around 90 AD, the same time as the Coliseum in Rome, it once held an audience of 20,000 people. It has 66 arcades on the ground floor and 60 arcades on the second storey. The main entrance is still the main entrance used today.

The arena was shaded from the sun by a large velarium (awning). Many of the corbels that once held the awning masts are still in place on the upper levels.

The relief of Romulus and Remus suckling the she-wolf is still fairly visible on the first level above the keystone across from the Palais de Justice.

The relief of Romulus and Remus suckling the she-wolf is still fairly visible on the first level above the keystone across from the Palais de Justice.

Inside the arena a 10’ tall barrier wall kept the spectators safe from the action. it still does.

Inside the arena a 10’ tall barrier wall kept the spectators safe from the action. it still does.

There was an underground network of passages, traps and lifts in the floor for raising scenery and animals. An underground inscription stated that T. Crispus Reburrus built it but no-one is sure if he just built the underground system of the entire amphitheater.

By 472, the amphitheater was turned into a fortress. By the 8th century, Saracens from North Africa invaded Nîmes and used the arena as their stronghold. Legend holds that the black patina on the stones is supposedly from the fires when Charles Martel tried to burn the invading Arab Saracens out of the arena in 736.

These days the Nîmes Amphitheater is the home of the Fiera de Nîmes, an annual Spring bullfight around the Pentecost. The entire city is filled with parades, concerts and yes, bullfights. These brutal contests, normally excluded to Spain, are very popular in both Nîmes and Arles.

As distasteful as the Bullfights might be to many people, this blood sport has provided more than enough funds to restore much of the Arena.

A section of the outer wall has been replaced with the same stone of the original arena, a labor of local stone masons that has got to be one of the best paying jobs in the world.

Aside from the annual spring Bullfight season, every July, the amphitheater hosts the Festival de Nimes featuring local and world class music acts.

The Musée de la Romanité is currently under construction across from the Nîmes Arena. The design by French Brazilian architect Elizabeth de Portzamparc is set to open in 2018. It will incorporate the Roman collections of the Musée Archéologique and a living roof garden. There is a good collection of Roman antiquities currently under wraps in the Nîmes Archeological Museum but most likely the new museum will incorporate collections from Roman Museums throughout France.

The Musée de la Romanité is currently under construction across from the Nîmes Arena. The design by French Brazilian architect Elizabeth de Portzamparc is set to open in 2018. It will incorporate the Roman collections of the Musée Archéologique and a living roof garden. There is a good collection of Roman antiquities currently under wraps in the Nîmes Archeological Museum but most likely the new museum will incorporate collections from Roman Museums throughout France.

Water was the source of life to ancient Rome. If the water wasn’t there, they’d go an get it.

Water was the source of life to ancient Rome. If the water wasn’t there, they’d go an get it.

In Nîmes we can still see one of the water distribtion tanks known as the Castellum Divisorium.

This late 3rd century water distribution is around 20’ in diameter and about 4.5’ deep. A walkway across the tank enabled workers to keep it clean.

As the water filled into the tank it was dispersed through 10 lead pipes to various fountains, baths and homes. The tank was also equipped with paths for the fresh water to flow through the sewer system. Clean water in, clean water out. It’s been estimated that somewhere between 5 and 10 million gallons of water per day came through this tank.

The Castellum is in pretty good condition. The exterior structure once built to protect the tank is gone. It was rediscovered in 1844 but no-one really knew what it was till 1875. Now it site protected in a small residential area northeast of the Jardins de la Fontaine.

The source of the water arriving the Castellum was 50km away from the Fountain d’Eure, a large spring near the town of Uzès. Water from the spring still serves Uzes with a steady flow of about 12 gallons per second, or over 1 million gallons per day. The water flowed through the granite mountains and over the Pont du Gard, the greatest Roman Aqueduct Bridge still in existence.

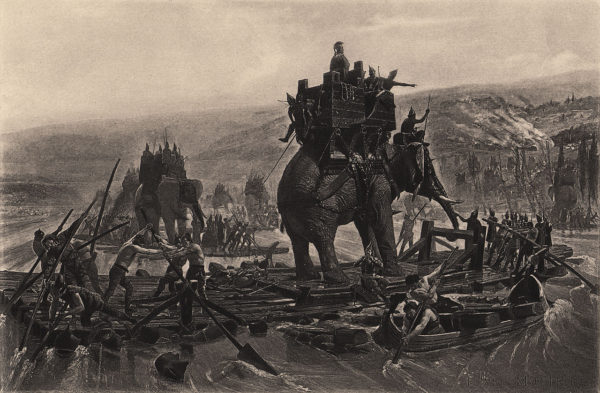

Pont du Gard

Although the Pont du Gard is actually a bit north of the via Domitia, without it, there would be no Nîmes. As the crow flies, the distance from the Uzès water source to Nîmes is only about 12 miles. By land, it’s a lot longer. It bends, turns, straddles rivers, goes through solid granite and traverses the Pont du Gard Bridge across the Gardone gorge. This is the longest aqueduct bridge in the world, close to 1,000’ long.

Although the Pont du Gard is actually a bit north of the via Domitia, without it, there would be no Nîmes. As the crow flies, the distance from the Uzès water source to Nîmes is only about 12 miles. By land, it’s a lot longer. It bends, turns, straddles rivers, goes through solid granite and traverses the Pont du Gard Bridge across the Gardone gorge. This is the longest aqueduct bridge in the world, close to 1,000’ long.

Pont du Gard is actually three bridges built on top of each other, all without mortar. The stones, weighing up to 6 tons, are held together with metal clamps. This youtube video will give you a very good idea of this amazing achievement.

The altitude difference from the source to the city was 56 feet. The engineers needed to make the water fall no more than 17 inches per mile to keep a steady flow. Each stone needed to be measured and placed exactly in the right location regardless of whether the path was high over the Gardon River gorge or through the mountains.

The altitude difference from the source to the city was 56 feet. The engineers needed to make the water fall no more than 17 inches per mile to keep a steady flow. Each stone needed to be measured and placed exactly in the right location regardless of whether the path was high over the Gardon River gorge or through the mountains.

This incredibly designed aqueduct delivered over 9.2 million gallons of water each day to Nîmes for over 200 years. Over the years, wealthy landowners bored holes into the aqueducts, siphoning the water for their own personal use. Eventually channels would block up with calcium deposits and tree roots. Maintenance was costly and not kept up very well and by the 3rd century the volume was reduced to around 2.6 million.

Because of the height of Pont du Gard (over 165’), it required 3 levels of arches to hold the weight of this massive aqueduct. You can still see the brick supports for the scaffold structures used to lay the upper levels.

Although no one is certain who is responsible for the construction. We like to think it was Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa around 19 BC, around the same time he was the magistrate of Public Works (Aedile) in Rome, where he took a special interest in building new Aqueducts for the city.

It is often said that the Emperor Augustus claimed to have “found Rome in brick and left it in marble”, but it was actually Agrippa who rebuilt the 1st century city, paying for much of it from his own pocket. In Rome Agrippa rebuilt the sewer system, built a Bath complex (next to the Piazza Rotunda), built the (original) Pantheon, the Portus Julius Naval Base south of Rome at Cumae and two new Aqueducts: the Aqua Virgo and the Aqua Julia. It is very probable he had his hand in the construction of the Pont du Gard.

Pont du Gard took 5 years to complete. The entire run of the aqueduct from Uzès to Nîmes took another 15 years. The bridge has survived pillaging, floods, earthquakes and the 1622 destruction when Henri II, the Duke of Rohan cut away 1/3 of the thickness of the entire second tier of arches to create a path to transport his cannons across the river during the war against the Huguenots. The damage was repaired in 1703.

In 1745 the second bridge was attached to the aqueduct. Cars crossed the bridge road till the late 1990s. Now it’s a pedestrian only crossing.

In 1745 the second bridge was attached to the aqueduct. Cars crossed the bridge road till the late 1990s. Now it’s a pedestrian only crossing.

In 1855, Napoleon III sponsored a major restoration. During this time the stairs were built at one end to allow access to the top channel, although this access is no longer available to the public.

In 1855, Napoleon III sponsored a major restoration. During this time the stairs were built at one end to allow access to the top channel, although this access is no longer available to the public.

When the channel was first constructed it was covered with a waterproof layer of layer of quartz and terracotta to keep the water from contamination. it worked for a while. every so often aqueduct repairmen needed to get inside the channel and clean it but the maintenance was never kept up. A combination of corruption and calcium eventually defeated the aqueduct. Still, water flowed through the channel for close to 400 years.

Pont du Gard is easy to find. The €18 price includes parking, the bridge, a movie about the history of the Pont du Gard and one of the most amazing museums ever created for a Roman monument. It is an actual recreation of the site and construction. You could easily spend a half a day there, or more.

One more note. It has been determined that the aqueduct is tilting a few millimeters each year. Eventually it will need further support. I am always aware of how lucky we are that we can still see these magnificent ancient wonders.

Mas des Tourelles

Before we head over to St Remy de Provence and Glanum, I’d like to add a visit to the Mas des Tourelles. The farm is located about 12.5 miles (25 minutes) west of Saint Remy de Provence.

Although Mas de Tourelles is not really an ancient site, it is a worthwhile stop. The Mas produces wine in the ancient Roman way.

The grapes are foot stomped and then put through an ancient style Roman wine press and then stored in replicas of ancient dolia earthenware vessels.

The grapes are foot stomped and then put through an ancient style Roman wine press and then stored in replicas of ancient dolia earthenware vessels.

The Mas specializes in the ancient offerings. They are all based on ancient roman recipes and all very unique and they are not expensive.

Mulsum, a wine mentioned by Pliny the Elder, is a blend of grapes, honey, cinnamon, pepper, thyme and other spices.

Turriculae, made according to the recipe of the 1st century agriculturist, Lucius Columella, is a mixture of boiled grape juice, fenugreek and a bit of seawater.

Carenum, as described by 4th century agriculturist, Palladius, is a sweet amber colored wine mixed with quince juice.

The harvest and vinification occurs every year around the second week of September. We arrived a week later. We missed the foot stomping and pressing but we did get to see the vats of fermenting juice in large clay dolia half buried in the ground to keep the temperature cool.

Saint Rémy de Provence and Glanum

Saint Rémy de Provence is a beautiful small town in the shadow of the Alpille Mountains. It was the birthplace of Nostradomus, the 16th century mystic who is still predicting historic events. It’s where Vincent Van Gogh received psychiatric care after he cut off his ear. The town was once owned by the Grimaldi family of Monaco; Prince Rainer, Grace Kelley, Caroline, Stephanie and Albert II, but these days the Grimaldi villa has been transformed into the Van Gogh museum.

Saint Rémy de Provence is a beautiful small town in the shadow of the Alpille Mountains. It was the birthplace of Nostradomus, the 16th century mystic who is still predicting historic events. It’s where Vincent Van Gogh received psychiatric care after he cut off his ear. The town was once owned by the Grimaldi family of Monaco; Prince Rainer, Grace Kelley, Caroline, Stephanie and Albert II, but these days the Grimaldi villa has been transformed into the Van Gogh museum.

The ancient settlement of Glanum is 1.6 kilometers from the center of Saint Rémy, a leisurely 20 minute walk.

Glanum was named for the Celtic god, Glanis, a healing god associated with the springs that once fed the settlement. Romans and Celtic Gauls alike considered gushing springs places where deities reigned supreme. Many of the settlements in the Provincia were named for the water gods who dwelled there before the Romans came in 58 BC.

Glanum was taken by the Greeks of Massilia (Marseille) and given to the Romans in 101 BC, but making it into a proper Roman town didn’t really happen until Julius Caesar came in 59 BC.

Caesar was appointed Governor of Gallis Narbonnensis in 59 BC. He was broke when he arrived and saw the riches of Gaul as a way to pay off the debt he incurred in his election as Consul. He took 4 legions with him; Legio VII, Legio VIII, Legio IX Hispana and Legio X. Each legion had between 5,000-6,000 troops. By the end of the 8 year campaign, over a million Celtic Gauls were killed.

After the Roman civil war of 49 BC, Caesar took control of the Provincia, destroying towns that were loyal to his enemy, Pompey Magnus, and rewarding towns loyal to Caesar. Glanum fell into the later category.

Although Caesar started the Romanizing of Glanum, it was his adopted son, Augustus, who created most of what we see today.

Roman Glanum was destroyed and looted in 260 AD by the Alemanni, a German tribe from the upper Rhine. In the middle ages, it was pillaged for materials and then all but forgotten until the 1920’s when Archaeologists Jules Formigé and Henri Rolland rediscovered the ruins. Formigé was instrumental is the preservation of many of the Roman sites throughout Provence.

Roman Glanum was destroyed and looted in 260 AD by the Alemanni, a German tribe from the upper Rhine. In the middle ages, it was pillaged for materials and then all but forgotten until the 1920’s when Archaeologists Jules Formigé and Henri Rolland rediscovered the ruins. Formigé was instrumental is the preservation of many of the Roman sites throughout Provence.

The site is well described in many websites and books It requires some imagination to see how great the city was in the 1st century.

There are some wonderful pieces propped up around the ruins, the Bouleuterion arena, the Sacred Well and Sacred Spring of the water gods, the Bath Houses, the remains of ancient Greek fountains and three columns of the Temple of Valetudo (goddess of health) built by Marcus Agrippa around 20 BC.

There are some wonderful pieces propped up around the ruins, the Bouleuterion arena, the Sacred Well and Sacred Spring of the water gods, the Bath Houses, the remains of ancient Greek fountains and three columns of the Temple of Valetudo (goddess of health) built by Marcus Agrippa around 20 BC.

Most people gravitate to the big hits known as Les Antiques de Glanum. They are two large remains that once stood at the entrance and just outside the entrance. They still sit outside of the ancient city.

The 60’ tall Mausoleum of the Julii is mostly thought to be the mausoleum of the Julii Family (mother, father and three Julii brothers), although it might have also been a Cenotaph, an empty tomb erected in honor of the family.

The 60’ tall Mausoleum of the Julii is mostly thought to be the mausoleum of the Julii Family (mother, father and three Julii brothers), although it might have also been a Cenotaph, an empty tomb erected in honor of the family.

Julius Caesar was of the Julii family. So was Augustus and every Emperor through Nero. The mausoleum is dated to around 20 BC, during the time of Augustus. Most likely this was one of the wealthier families of the settlement.

The monument is in excellent condition, although much of it is reconstructed. The top conical structure surrounded with Corinthian columns is the temple dedicated to the line of Julii men. Most likely the father and grandfather might be the statues in the lantern of the monument. The fish scale ornamentation is typical of Roman mausoleums of the period.

The frieze below the conical temple has the inscription from Sextus, Lucius, Marcus, sons of Caius, of the Julian Family to their parents.

The frieze below the conical temple has the inscription from Sextus, Lucius, Marcus, sons of Caius, of the Julian Family to their parents.

The lower frieze is decorated with mythological scenes, the Trojan War and tales of heroic victory in Gaul.

It’s not known if the Julii were soldiers but nonetheless, their glory has lived on for over 2000 years.

The Triumphal Arch (the oldest Triumphal Arch in France) was the grand entrance to the city along the via Domitia.

The Triumphal Arch (the oldest Triumphal Arch in France) was the grand entrance to the city along the via Domitia.

Some say it was dedicated to Caesar’s victory in 50 BC, some say it was Augustus’ victory in 27BC .

It was once over 36’ tall but most of it has been carted away from other building projects. Even though most of the grandeur has been stripped away over the years, it is still an impressive piece.

The sides of the Arch are adorned with images of defeated Gallic prisoners. Casting the vanquished on Triumphal Monuments was a common theme in ancient Rome. It glorified the victors and left a warning for anyone who might rise up against the empire.

The sides of the Arch are adorned with images of defeated Gallic prisoners. Casting the vanquished on Triumphal Monuments was a common theme in ancient Rome. It glorified the victors and left a warning for anyone who might rise up against the empire.

This detail showing a couple in chains is still a sad testament to the horrors of war. These prisoners were undoubtedly separated, never to see each other again.

By the way, as I already mentioned, the Mausoleum of the Julii and the Triumphal Arch are still outside the town. Although there is a €9.50 entrance fee to see the Glanum site (highly recommended), these two grand pieces sit along the Route des Baux-de-Provence (Route D5). You can visit them day or night for free.

Les Baux de Provence and Les Trémaïés

In 109 BC the northern Celtic Cimbri and Teutones tribes moved south, a flood of humanity, taking whatever they needed as they passed. By some accounts, there were over 300,000 of them.

In 109 BC the northern Celtic Cimbri and Teutones tribes moved south, a flood of humanity, taking whatever they needed as they passed. By some accounts, there were over 300,000 of them.

The Roman troops in the Province were no match for them. In 105 BC, Rome suffered its worst defeat to date when the Cimbri and Teutones wiped out 80,000 Roman troops and 40,000 Roman allies near Orange. The Cimbri and Teutones were flushed with confidence and many in the Roman Senate thought they had shifted their course and appeared to be heading towards Rome.

Even though the Sack of Rome by the Gauls was 280 years earlier, the legend of horror still remained in the collected memories of Roman citizens. For years after the 390 BC sack of the city, Rome would perform human sacrifices, burying Gallic men alive in order to avert another attack. Now they needed to stop the Gallic invasion before it ever got close to the city walls.

They called on General, Gaius Marius, the hero of north Africa who had just defeated Roman public enemy #1, Jugurtha, the King of Numidia.

Marius watched the Celtic horde for three years, refusing to engage in combat until he had all the elements in his favor. Then, in 102 BC, in a clearing near Aix-en-Provence, he attacked.

When the battle was over, over 90,000 Teutones and Ambrones were dead and over 40,000 sold off into slavery.

A year later, Marius caught the remaining Cimbri in at the Battle of Vercellae (near modern day Parma in Emilia Romagna). According to historical accounts, over 140,000 Cimbri were killed and 60,000 sold into slavery. Although all these numbers of dead and enslaved are written down by Roman historians, it is very likely they were inflated a bit to throw more glory on the victory.

Marius became a legendary hero. Marius (or Maïus) is still one of the most popular names in Provence.

The story of Marius plays into the small town of Les Baux de Provence, about 15 minutes south of Saint Rémy de Provence in the shadow of the granite peaks of the Alpilles Mountains.

The main attraction here is the 10th century mountain fortress known as the Chateau des Baux, home of the Lord of les Baux who claimed to be descendants of Balthazar, one of the Three Magi who visited the Christ child.

In 1821, a geologist named Pierre Bethier discovered the stone of the mountain to have a high concentration of aluminium. The stone was named Bauxite (after the town). It is still the main source of aluminium in the world.

These days Chateau des Baux is one of the largest attractions in Provence. It’s a cute fortress town with lots of shops and restaurants. The Chateau also showcases some of the best ancient siege engines replicas, including the largest trebuchet in Europe.

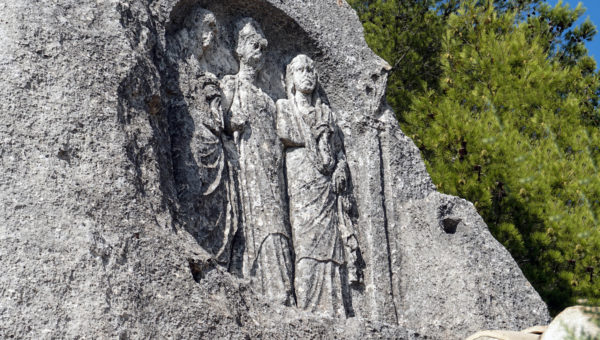

The Roman interest here is the 1st century bas relief carved into the granite and bauxite mountain stone known as “Les Trémaïés”, the Three Marys.

The Roman interest here is the 1st century bas relief carved into the granite and bauxite mountain stone known as “Les Trémaïés”, the Three Marys.

According to Medieval Catholic historians, the 1st century carving was a commemoration to Mary Magdalene, Mary Salome (mother of Saint James and St John) and Mary of Jacob, the three Mary’s who witnessed the crucifixion of Christ and fled to Roman Gaul.

Mary Magdalene is believed to be buried in the crypt of the Basilica Saint Mary Magdalene in the Vézelay Abbey at Saint Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, about 25 miles east of Aix-en-Provence.

Another version removed Mary of Jacob and replaced her with Mary of Clopas. When someone pointed out that one of the three figures was actually a man, the engraving became Mary Magdalene with her sister Martha and her brother Lazarus. The explanation changed but the name, The Three Marys, remained. Lazarus might be the first man ever to be called a Mary.

The rock is poised above to the Chapel of Trémaïés which has held it up on the mountain for centuries. The Chapel has most likely saved the stone from falling down the precipice.

However, there is another (much more plausible) explanation for Les Trémaïés. In 1870, Isidore Gilles, an aristocratic amateur archaeologist from Saint Remy de Provence claimed the figures to be representations of Gaius Marius, his wife Julia and the Syrian Priestess Martha, the psychic adviser who always traveled with him. The figure wearing an Eastern headdress is Martha. The figure dressed in a toga, the vestments worn by a Consul of Rome, is Marius. The remaining figure is Julia, the wife of Gaius Marius and the aunt of Julius Caesar.

Apt and the Pont Julien

The best preserved Roman stone arch bridge along the via Domitia is the 264’ long 3 arched Pont Julien. It crosses the Calavon River about 12 minutes west of the beautiful town of Apta Julia (modern day Apt).

The best preserved Roman stone arch bridge along the via Domitia is the 264’ long 3 arched Pont Julien. It crosses the Calavon River about 12 minutes west of the beautiful town of Apta Julia (modern day Apt).

The bridge was built in 3 BC, around 115 years after the first part of the via Domitia was laid. This is a remarkable piece of ancient engineering, built to withstand the floods of the Spring rains and the snow melt in the mountains. The arched vents built into the supporting piers were designed to alleviate the pressure of the flooding river and let the water flow thrown the bridge instead of knocking it over.

The Pont Julien carried everything from ancient carts to large automobiles until 2005 when in consideration for its preservation it was turned into a pedestrian or bicycle traffic only.

There is nothing Roman in the nearby town of Apt, however, this is the place where in 121 AD, the Emperor Hadrian erected a monumental tomb for his favorite horse Borysthenes Alanus. The tomb is no longer there, nor is the inscription. All we have is the tribute Hadrian wrote to his faithful companion:

Borysthenes Alanus, the swift horse of Caesar, who was accustomed to fly through the sea and the marshes and the Etruscan mounds while pursuing Pannonian boars.

Not one boar dared him to harm with his white tooth.

The saliva from his mouth scattered even the meanest tail, as it is custom to happen.

But killed on a day in his youth, his healthy, invulnerable body has been buried here in the field.

The are many other places in Provence, Languedoc and Côte d’Azure to find remains of the Roman period. There is a nautical museum in Marseille, ruins and arches in Cavaillon (Cabelio), Sisteron (Segustero) and Gap (Vapincum) along the via Domitia. There are also sections of the ancient roads set aside for day hikes.

If you wish to find more information on the Roman Province I highly recommend the book ‘The Roman Remains of Southern France’ by James Bromwich. The book is out of print but there are still copies available. Another great resource is The Roman Provence Guide by Edwin Mullins. Much of the information used in this article was provided in these two books.

The Provincia of Rome was looted, destroyed, repurposed and thankfully put back together thanks to Prosper Mérimée when he was the Chief Inspector of Historic Monuments in the mid 19th century.

Mérimée is most noted as the author of the novella Carmen that became the Bizet’s Opera of the same name, however, he did a lot more than giving the world the story of the gypsy Carmen. Mérimée saved the UNESCO city of Carcassonne from destruction and saved so many of the Roman antiquities in France. We owe him our deepest thanks.

You must be logged in to post a comment.