The statue of Athena upon the Acropolis suddenly turned to the west and spit blood. – Cassius Dio (AD155-235)

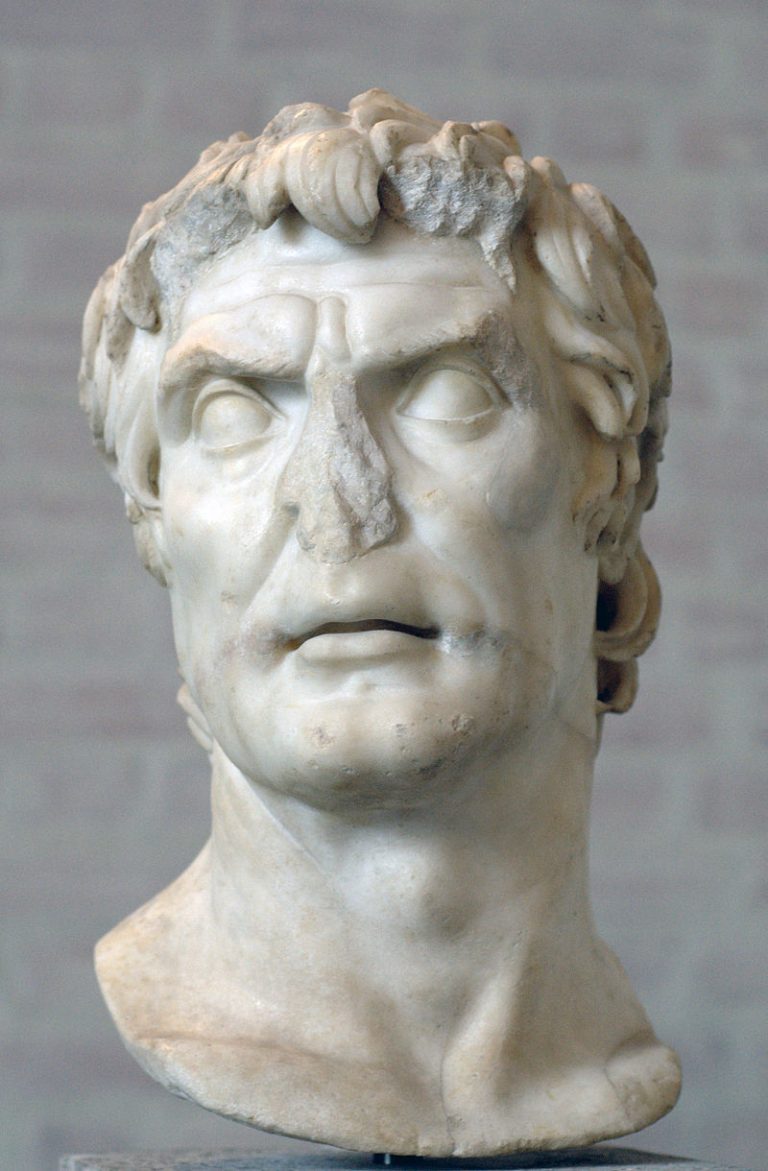

In 87 BC, during the 1st of the Mithridatic Wars of Rome vs Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus, Roman General Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix laid siege to both Athens and the Athenian Port of Piraeus.

Sulla, whose surname was given in recognition of the red blotches covering his face, couldn’t breech the strong Athenian fortifications but he was able to cut off supplies. After a 5 month long siege, deserters from the city revealed a weak point in the walls. At midnight on March 1, 86 BC, the armies of Sulla breached the walls. When the invasion was finished, most of the city was burned to the ground and much of the population lay dead in the streets.

Athens did rebuild under Roman rule. The Roman elite (and ruling class) had an elevated regard for Athens as the center of higher knowledge. Everyone from Julius Caesar, to Pompey Magnus, Mark Anthony, Augustus, Cicero and Ovid studied in Athens. Greek was the language of the educated. Latin was the language of the streets.

In 31 BC, Gaius Octavius, the future Emperor Augustus, defeated the forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra off the coast of Actium in western Greece. They were aided by some Greek city-states, most notably Sparta. Athens was most notably a supporter of Mark Antony, a point remembered by Octavius when he first visited the area as the Emperor Augustus in 21 BC to reorganize the Greek provinces. He was still angry at Athens and chose to stay in Aegina, an island about 50 km southwest of the city.

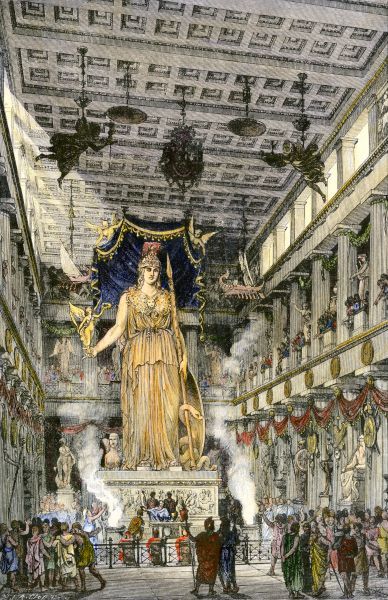

Of course, the Athenians were still pissed off at Augustus and, according to Cassius Dio, when Augustus did visit Athens in the winter of 21 BC, the statue of Athena Polias on the Acropolis Altar of Athena Polias, which had always faced to the east, suddenly turned to the west and spit blood in the direction of Rome.

Eventually, Augustus softened his anger towards the Athenians. He actually felt a great respect for Athens and in many ways he wanted to reshape the appearance of Rome to look like the Golden Age of Athens under Pericles in the 5th century BC.

When Augustus returned to Athens in 19 BC, he came to make peace with the Athenians and rebuild the grandeur of the ancient city.

The Agora Marketplace

When Augustus came to Rome in 19 BC he brought with him architects, contractors and his best friend, best General, best builder and son-in-law, Marcus Agrippa.

Around 19 BC, Agrippa had building projects going up all over the Roman Empire. In Gaul, he had the Pont du Gard and the Temple to Augustus (Maison Carrée) in Nîmes. In Rome, his Aqua Virgo aqueduct was completed and the Arch of Augustus (no longer existing) was erected in the Forum.

In Athens, he began work on the Agrippeion, his Odeon theater.

After the Great Marketplace on the island of Delos was destroyed in 80 BC, during the Mithridatic wars, much of the trade was relocated to Athens, even though the Athens Agora was severely damaged during the siege of Lucius Sulla in 87 BC.

In 51 BC, Athens send their Ambassador, Herodes of Marathon to Rome to requests aid to rebuild the city. In 47 BC, Julius Caesar approved funds to rebuild the run-down Agora. He would have added more but he was assassinated in 44 BC.

It was Augustus who is responsible for most of the renovations of the 1st century BC. The Emperor Hadrian finished the restoration in the 2nd Century. We’ll spend more time with Hadrian a little later.

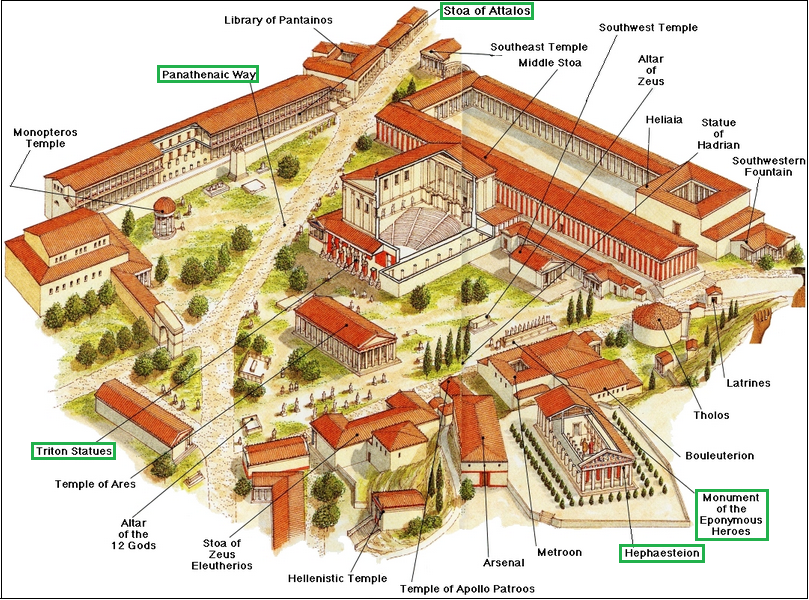

The Agora was a large open area with a series of stoas (covered colonnades) around the perimeter. There were spaces for shops inside the stoas and a mass marketplace in the open center.

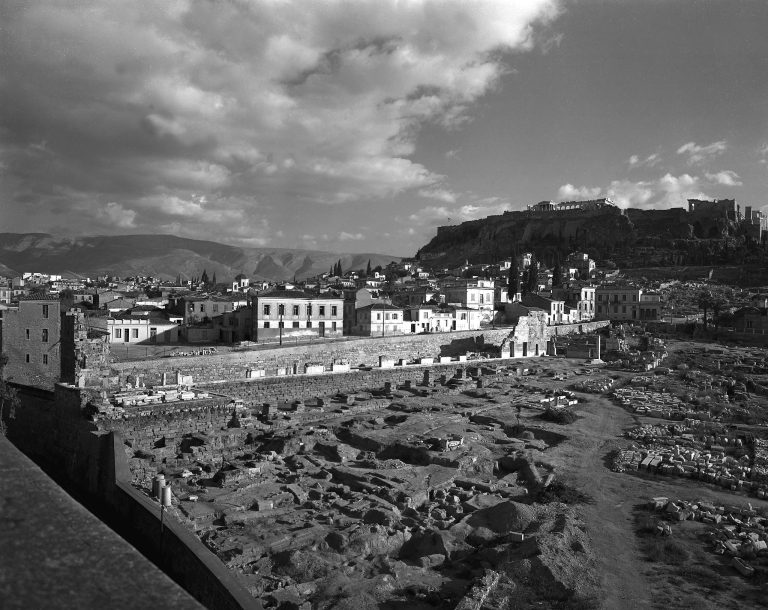

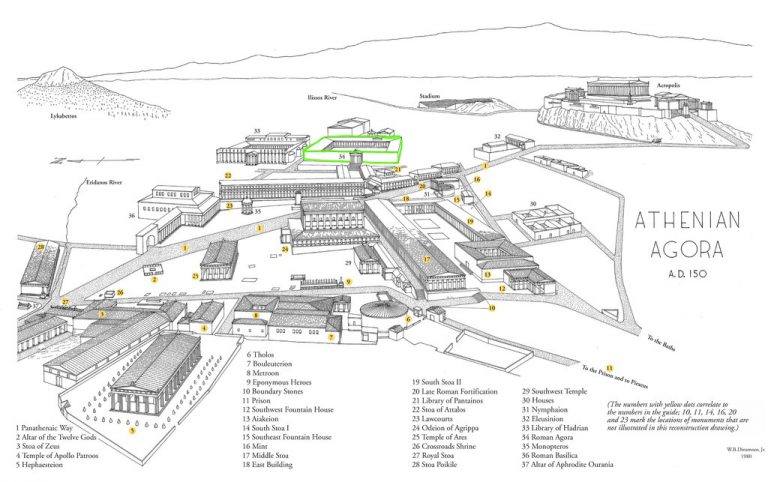

The illustration here gives an idea of the how the Agora looked in the 2nd century. By this time the Agrippeion (Agrippa’s Odeon theater) had collapsed and was rebuilt. More about this in a minute. The labels outlined in green are still in the Agora. The rest of it is gone.

When the Greek Agora was rebuilt it became more Roman. The central square of the Athenian marketplace was once filled with merchant stalls. The new Roman reconstruction included a Temple to Ares and Agrippa’s 1000 seat Odeon theater.

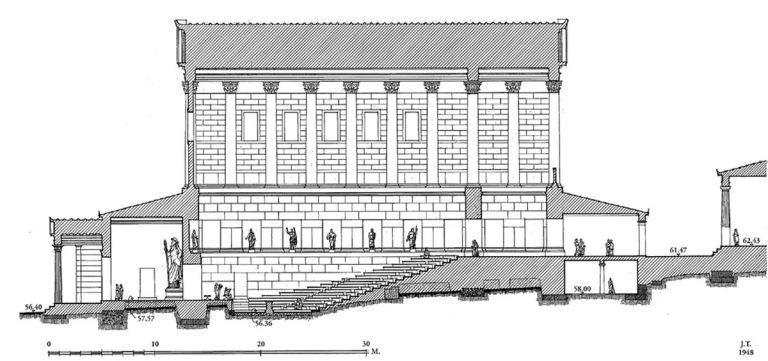

The enormous covered Odeon was finished in 15 BC. It was modeled on the roofed Odeon of Pompeii built in 80 BC that held 1500 people. The Pompeii Odeon was still standing in 19 BC when Agrippa borrowed the design. Pompeii wasn’t destroyed until 79 AD.

The Agrippa Odeon, known as the Agrippeion or the Kerameikos Theater, had an entrance in the back through the terrace of the middle stoa and an entrance in the front for performers and VIP who would sit down near the orchestra.

There was a rectangular stage, a semi-circular orchestra and an auditorium covered with a pitched roof with no interior support.

The building lasted for more than 100 years until the 25 meter span opening in the auditorium collapsed. No one is really certain if the collapse was due to the design but nonetheless, it fell.

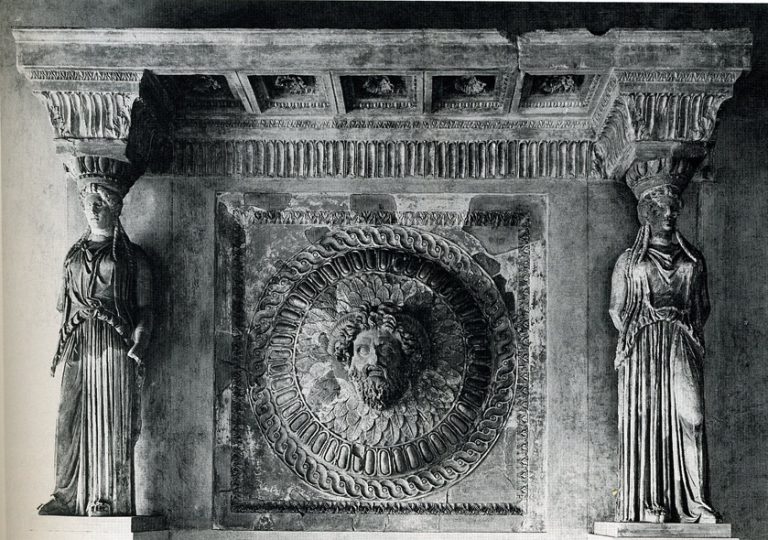

The rebuilt Odeon of 150 AD cut the audience size in half and reconfigured a new entrance at the front with a large porch held up by tritones (male Mermen) with fish tails.

The rebuilt Odeon of 150 AD cut the audience size in half and reconfigured a new entrance at the front with a large porch held up by tritones (male Mermen) with fish tails.

These statues (photo above) now line the Panathenaic Way, the pathway through the center of the Agora. They are all that’s left of Agrippa’s Odeon Theater.

The Odeon was destroyed in the AD 267 invasion of the Herulian. In AD 410, the remains of the Odeon were rebuilt into a Gymnasium known as the Palace of the Giants because 4 of the Tritones were used to adorn the entrance to the new building.

To the east of the Odeon, across the Panathenaic Way, was the grand two story covered colonnade Stoa of Attalos, originally built by and in honor of King Attalos II of Pergamon who ruled between 159-138 BC. It was a gift to Athens in thanks for the time the King spent studying in the city. Although the Stoa was built before the Roman occupation, it is an amazing restoration which is why I’ve included it in this article.

The Stoa marketplace was originally 116 meters long (380.5′) with space for 42 shops behind the colonnades. The reconstruction is actually a bit larger.

It was restored between 1952-56 by American Archeologists quarrying the same pentelic marble from Mt Penteli that was used in the original construction around 150 BC.

The restored version is a bit longer and now serves as the museum of the Ancient Agora.

The Museum is an interesting collection of artifacts from the 7th to the 5th century BC, including this terracotta baby potty chair from the 6th century BC.

At the north-west side of the Athenian Agora is the Temple of Hephaestus, the god of metalworking and craftsmanship. It is one of the best preserved 5th century BC Greek Temples in the world. Although the Temple was here during the Roman occupation, it was built in the 5th century BC, during the Golden Age of Athens.

There are other parts of the Ancient Agora I have not included only because the intention of this article is to showcase the Roman contributions to Athens but I have to include the Temple of Hephaestus because it is an amazing monument of antiquity.

The Temple is in the Theseion district of Athens which was named for the Temple which was once thought the be the Temple of Theseus, the founder of Athens. The remains of the Greek hero were alleged to be in the basement of the temple. Although the Temple was proven to be dedicated to Hephaestus, the neighborhood is still the Theseion.

The Roman Agora

Even with all the repairs and additions the Romans made to the Ancient Agora, it was still overcrowded. Well, the Romans did crowd the central market space with Temples and the Odeon theater.

The fix was to built another Agora to the east, behind the Stoa of Attalos.

The new Roman Agora was a 111 meter (364′) long x 104 meter (343′) wide enclosed peristyle courtyard.

The Roman Forum was similar to the Agora in that merchants sold their goods but different in that the Forum was also a place for legal affairs, religious worship.

The Roman Agora, sometimes known as Hadrian’s Market or the Imperial Market market controlled the olive oil markets. There were covered stoas around the perimeter and market stalls in the center of the square.

Some of the merchant stalls are still visible.

This stall had graduated holes for measuring amounts.

On this location along the stone perimeter of the Agora is an area designated as a merchant space by an inscription scratched into the stone. “τόπους” (pronounced toposh) is ancient Greek for “Merchant Space”.

There were two entrance/exits to the Roman Agora. The western gate known as The Gate of Athena Archegetis (Athena the Leader) was dedicated to the people of Athens and their patron Goddess, Athena. The gate, finished around 9 BC, was paid for with the money donated by Julius Caesar. The inscription on the architrave gives credit to Julius Caesar and Augustus for their generous donations and to the people of Athens who dedicated the Arch to Athena Archegetis.

The was also the decree of olive sales. Just inside of the Western gate is a column, which appears to have supported a door.

Inscribed on the column is the edict of the Emperor Hadrian regarding the tax obligations of the oil merchants. If you click and magnify the photo, you’ll be able to make out the Greek proclamation along the face of the column.

The edict reads that all oil producers must donate 1/3 of their production to insure that the city always had a sufficient amount of oil in reserve to sell at an affordable price.

The Eastern gate or Propylon to the Roman Forum, built in the Ionic order, is now just a series of columns with a pediment.

The steps and propylon lead up to an arched wall that was most likely part of a basilica where legal matters were carried out. The building is known as the Agoranomeion. However, it might have also been a Temple to the Imperial Cult of the Roman Emperors or even a support for an aqueduct that would have supplied water for the water clock in the Tower of the Winds sitting immediately to the left of the gate.

The Tower of Winds

Almost adjacent to the Roman Forum’s Eastern Gate is the Tower of Winds (the Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes), an octagonal marble clocktower built around 50 BC and named for Andronicus of Cyrrhus, a Syrian Astronomer, who gets credit for building the tower around 50 BC. There were sundials on all sides of the tower, and a weather vane in the form of the god Triton on the apex of the conical roof.

The 12.8 meter (42′) tall x 7.9 meters (26′) in diameter Tower is considered to be the world’s first meteorological station. Greeks invented the weathervane to foretell the weather patterns.

The staircase that surrounded the structure and the two classical porches off of each entrance/exit are gone but the doorways into the Tower are still in tact.

The Tower was also known as the Aerides (the winds). The Aerides neighborhood was named after the Tower.

Merchants in the Agora would use the Aerides to read the weather patterns and get an idea when their ships filled with goods might arrive.

The frieze panels below the roof line are what gives the Tower its name. Here you’ll see carvings of 8 wind gods: Boreas (North winter wind), Skeiron (Northwest) scattering ashes from a bronze vessel, Zephryus (West) a half naked youth scattering flowers, Caicias (Northeast) throwing hailstones on the people below, Eurus (Southeast) a bearded man wearing a warm coat, Apeliotes (East) bringing fruits and grains, Notus (South) the bearer of rain emptying a pitcher of water and Lips (Southwest) holding an aphlaston, the curved ornament from the stern of a ship, steering the ship.

A hydraulic water clock built inside the tower was fed by water coming off the Acropolis Hill possibly through an aqueduct off the Propylon Gate.

The dome is an intricate design of segmented slabs of stone that has lasted more than 2000 years. If the tower dome was built 75 years later it would have probably been made of a single span of concrete.

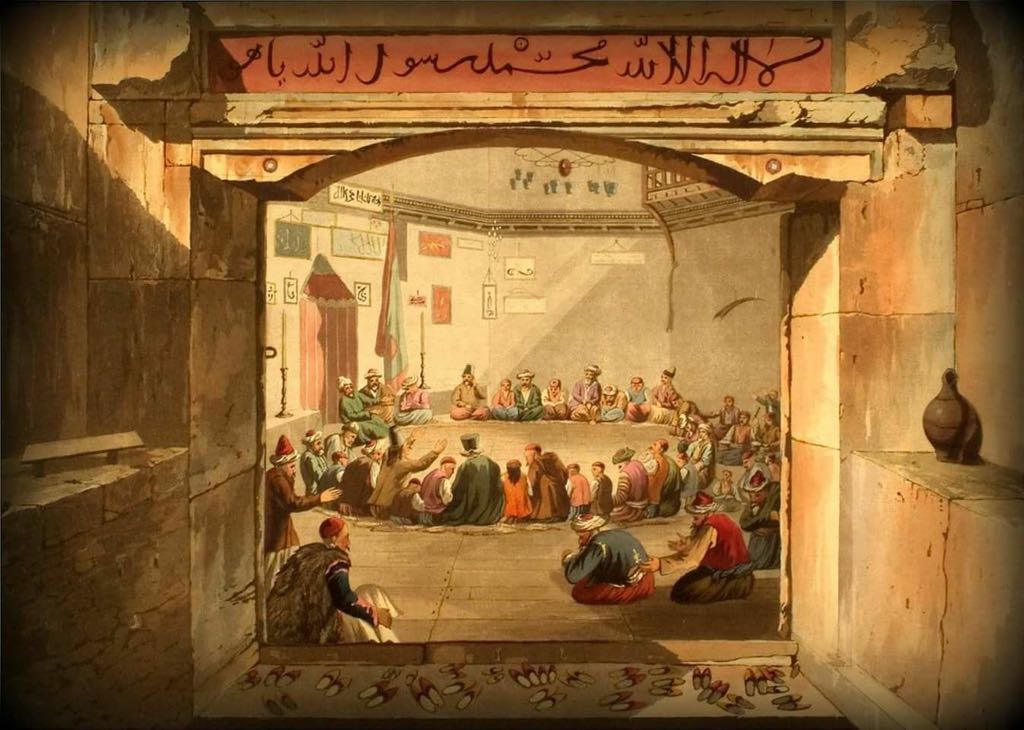

As Lord Elgin (Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin) was plundering the Acropolis Hill in 1801, he also had his eyes on the Tower of Winds, wanting to dismantle it and bring it back to England but the at the time, the Ottoman Turks, who occupied Athens from the 15th through the early 19th century, were using the Tower as a meditation retreat for Sufi Dervishes. The Sufi saved it from the greedy hands of Lord Elgin.

The Tower of Winds was just recently restored from 2014 to 2016. It’s now open to the public.

The Agora Public Toilets

Next to the Tower of Winds are the ancient Roman public toilets, the Vespasianae, once a square covered building with a square open center for ventilation. The name, Vespasianae, was (irreverently) named for the Emperor Vespasian (69-79 AD) who ordered a tax on urine. Many think the Vespasianae was the precursor to the Pay-Toilet but they are wrong. Yes, Vespasian declared a tax on urine but it wasn’t paid by the uriners. Urine was used in tanning leather and as a source of ammonia to clean woolen togas. The lower classes would urinate into pots and emptied into cesspools. The urine was then collected and sold to the vendors who used it. The vendors paid the tax.

Like all ancient Roman toilets, an under the seat water stream carried the waste away while another water stream in front of the guest would clean the toilet brushes. Romans used brushes made of sponges to clean themselves. In some cases the brushes were dipped into a mixture of vinegar and then rinsed in the flow of water. It was all pretty hygienic and much better than the port-o-toilets in use today.

In this recreation of an ancient Roman toilet, you can see how comfortable and hygienic they were. In many cases, wealthy patrons had their servants bring wooden toilet seats so they wouldn’t need to sit on the cold stone.

In this recreation of an ancient Roman toilet, you can see how comfortable and hygienic they were. In many cases, wealthy patrons had their servants bring wooden toilet seats so they wouldn’t need to sit on the cold stone.

For more information about the Agora of Athens, this site from the American School of Classical Studies in Athens is excellent.

Hadrian’s Library in the Roman Agora

The Emperor Hadrian (117 to 138 AD) was probably the greatest Roman Philhellene/Greekophile of all times. I have much more to say about Hadrian a bit further down in the article but since the Library is adjacent to the Roman Agora, it seemed appropriate to include it here.

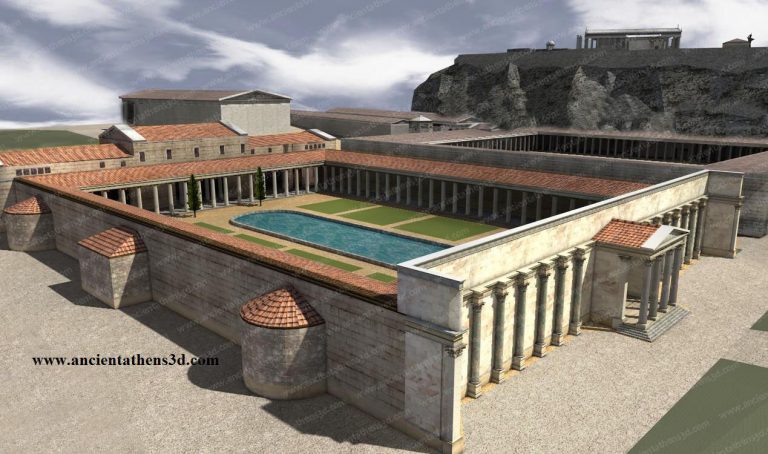

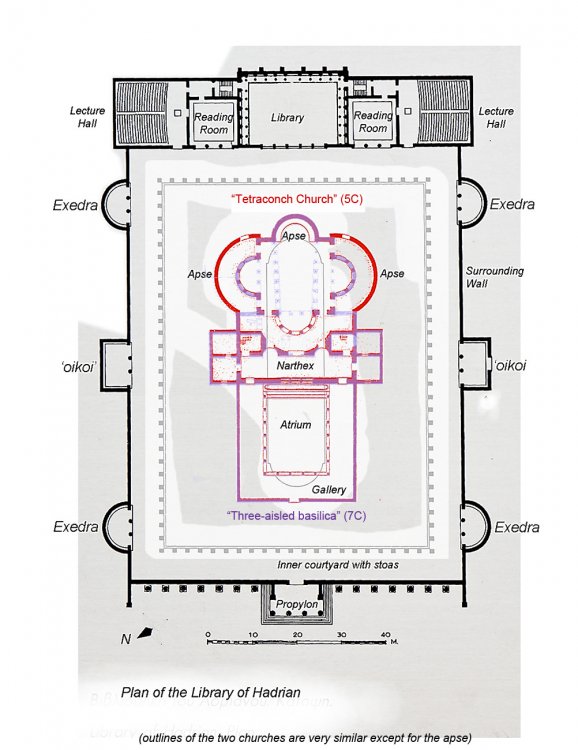

When Hadrian came to Athens for his final visit in 131 AD, he built his Forum next to the Roman Agora. Actually, the Forum was close to the same size as the entire Roman Agora. Over the years it has become known as Hadrian’s Library.

Hadrian’s Library was a 122 meters (400′) x 82 meters (269′) walled enclosure with an open air courtyard, central pool and gardens surrounded by Phrygian marble columns. It was modeled after Vespasian’s Forum (Temple of Peace) in Rome.

The libraries, reading rooms and lecture halls with curved amphitheater style seating were at the eastern end of the courtyard. Libraries were Temples of Peace and Meditation to Hadrian.

When the Heruli, a Germanic tribe from the Black Sea region, came down and sacked Athens in 267, the library suffered a lot of damage. It wasn’t fully repaired until 412 when Herculius, the Prefectus of the Illyricum finally donated the required funding.

During Byzantine times, a Christian Church was built in the courtyard. During the Ottoman Turk occupation, the library complex became the residence of the Turkish Administrator and later as a Mosque and Fortress.

A section of the entrance facade still remains.

The Libraries were built to the rear of the Forum, currently going through a restoration.

The scrolls were kept in niches or wooden boxes to keep them safe. In many cases a scroll was read to others in the auditoriums or the central gardens. Scrolls were not allowed outside of the Forum.

In the nearby Library of Pantainos in the Ancient Agora, built around 100 AD, during the time of the Emperor Trajan, there was a tablet with the rules of the Library:

“No book is to be taken out because we have sworn an oath and the Library is to be open from the first hour until the sixth.”

This means no scrolls allowed outside the library walls and the hours are from the 1st hour of daylight (around 7am) till the 6th hour (around 1pm).

There are very few ancient scrolls left in the world. I only know of three of them; the Dead Sea scrolls (1st century BC), the Herculaneum Papyri are from 79 AD, after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and the Bankes Iliad, a 2nd century papyrus scroll that now lives in the British Library.

When the city was rebuilt after the sack of the Heruli in 267, the Agoras were pushed outside of the Fortified walls. Consequent attacks by Alaric and the Visigoths in 395 and again from the Vandals in 470 and the Slavs in 583 pretty much decimated the ancient market places.

The Agoras were mostly abandoned in the 7th century.

The Acropolis Hill

When Augustus came to Athens in 19 BC, one of his first projects was the restoration the Caryatids, the female columns sculpted by Alkamenes, a student of Phidias, that supported the porch of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis Hill. One of the them was in such bad repair, Augustus had a Roman copy put in it’s place. The Roman copy is the 2nd from the right, although these are all copies so the Roman copy is a copy of a copy.

Five of the originals are put away in Athens for safe keeping. The 6th one, stolen by Lord Elgin in the 19th century resides in the British Museum. Greece and England have been fighting this one out for well over 100 years.

The caryatids copies replaced the originals on the Erechtheion in 1979.

Copies of the Caryatids were added to the Forum of Augustus, the original Pantheon built by Marcus Agrippa and Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli.

The originals, which were put in a dark museum on the Acropolis Hill have been released and restored and are now in the new Acropolis Museum. Four of them are complete. One is in pieces. There is an empty space where the 6th one should be, dramatizing the sentiment Greece feels for Lord Elgin and British Museum. I just have to add here, the caryatid in the British Museum is in the best shape of all them.

Yes, Lord Elgin did probably steal the Parthenon Marbles and the Caryatid but the British museum has done a great job in preserving them. However, now that Athens has this amazing Acropolis Museum, it might be time for the British Museum to make copies and send the originals back home.

The Caryatids represent maidens from the Peloponnesian town of Karyai who served the Temple of Artemis.

Although the most famous of these human columns are on the Acropolis Hill, Caryatids can now be found in some 36 countries around the world.

Augustus adopted a few other design elements from the Greeks. The image Jupiter Ammon, the ram headed god, appears on many Augustan Temples. Jupiter Ammon was originally the Greek god image of Zeus Ammon.

This frieze of the second story attic of the portico that flanked the Temple of Mars Ultor in the Forum of Augustus in Rome is a good example of the Augustan use of the caryatids and the shield of Jupiter Ammon. The shield could be a reference to the shields Alexander the Great hung in the Parthenon next to 300 suits of Persian armor after he defeated the Persians at 334 BC Battle at the Granikos River.

Other architectural forms adopted from the Greeks by Augustus were the Corinthian Columns, acanthus leaves and marble. Marble or Granite was seen as an extravagance during the Republic but Augustus made it very fashionable. Augustus claimed to have found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble, although much of the “marble” was actually a theatrical trick. The Roman craftsmen excelled at stucco (intonico) finishes and in many of the 1st century building the substructure was inexpensive brick or tufa limestone. The exterior was a smooth coat of white stucco, a mixture of lime and crushed marble.

Here is an example of the Roman stucco prowess from the Temple of Hercules in Rome.

The Propylaea and the Pedestal of Marcus Agrippa

As you walk up the path to the Acropolis you’ll first arrive to the 5th century stairs leading up to the BC Propylaea, a central building with two wings, giving a monumental and controlled entrance into the Acropolis Hill.

As you walk up the path to the Acropolis you’ll first arrive to the 5th century stairs leading up to the BC Propylaea, a central building with two wings, giving a monumental and controlled entrance into the Acropolis Hill.

The Propylaea began construction in 437 BC but was never fully completed. Work on the grand entrance was halted in 431 BC due to the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta. When Athens lost the war, it was pretty much the end of the Golden Age of Greece.

Although Athens was sacked a few times between the 1st century BC and the 5th century AD, the Propylaea stayed undamaged until September 26, 1687 when the Venetian bombardment of the city blew up an Ottoman munitions depot inside the Parthenon. The damage was extensive. Over a 100 years later, in 1803, Thomas Bruce (Lord Elgin) obtained permission to make drawing of the antiquities on the Acropolis Hill. What he never mentioned was he wanted to make the drawings of the pieces back in England. The Parthenon marbles and one of the Caryatids have been in the British Museum ever since. Greece has been trying to get them back since 1983.

In 1981, Melina Mercouri, the Greek actress and star of such films as “Never on a Sunday” and “Topkapi”, was appointed the Minister of Greek Culture. In 1983, Mercouri mounted the campaign to bring back the Elgin Marbles but to no end. The marbles remained in the British Museum. Even though she didn’t get the marbles, in 1984, Mercouri convinced the Greek government to rebuild the Acropolis Hill. The reconstruction would have never been completed if it wasn’t for the Olympic Games of 2004. Even with the Olympics, the work on the Propylaea and the Acropolis Hill wasn’t completed until 2009. I’m mentioning all this because the Parthenon was built between 447-432 BC, 15 years. It took 322 years to partially reconstruct it. Actually the reconstruction is ongoing. The hill has been a mixture of ancient temples and modern scaffold for years. There is no timeline for completion. when one project is completed, another one begins. It is one of the most wonderful archeological digs in the world.

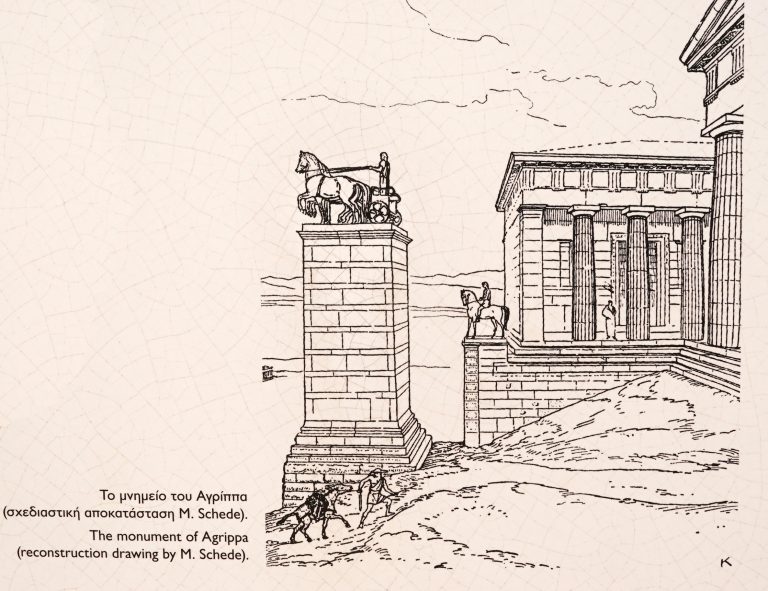

Pedestal of Agrippa

Prior to entering the Propylaea, there is a large pedestal on the left side of the path. It was built by in 178 BC by Eumenes II, the Hellenistic King from Pergamon and brother of Attalos II, the King who gave Athens the grand double story stoa in the Agora. Eumenes II built the pillar to honor himself and there was once a statue of him at the top of the monument.

Around 19 BC, it was altered by Marcus Agrippa, who replaced the statue of Eumenes II with one of himself. It’s one of the rare examples of Agrippa giving himself recognition.

Around 19 BC, it was altered by Marcus Agrippa, who replaced the statue of Eumenes II with one of himself. It’s one of the rare examples of Agrippa giving himself recognition.

Temple of Augustus and Rome

Augustus needed to plant the Roman flag on the Acropolis Hill but he did it with respect to the great history of Athens. Actually, the Temple of Augustus and Rome was built by the Athenians in honor of their new Emperor and patron.

The Temple of Augustus and Rome was a small tribute, a circular colonnade of nine columns, 8.6 meters (28′) in diameter and standing 7.3 meters (24′) tall under the conical roof, about 1/2 the height of the Parthenon.

Few pieces of the round foundation, columns and architrave remain. It’s not much. Most people walk past it. The dedication on the architrave, now sitting on the ground, tells of the gift to Augustus and Rome from the people of Athens.

Odeon of Herodes Atticus

On the southwest slope of the Acropolis Hill is the beautiful 2nd century Odeon of Herodes Atticus, known as the Herodeion.

Agrippa’s Odeon in the Agora once held 1000 people until the 25 meter (82′) clear span over the auditorium collapsed. Although the new Odeon of Agrippa was rebuilt around 150 AD, the capacity was cut in half to around 500.

Theater for the Greeks was like Horse Racing to the Romans. The crowd sizes were enormous and a theater for 500 people couldn’t cut it. A new theater was needed.

In the year 160, Herod Atticus (Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes), the most celebrated orator of his time, built the theater in honor of his Roman wife Aspasia Annia Regillia. It had 35 rows of seating for a capacity of 4,680 people under a covered roof. Now this was a proper theater for the people of Athens.

The Odeon of Herodes Atticus became the most prestigious theater in Greece.

Herodes Atticus was so successful he even had his own stone quarry. All the marble used came from his personal quarry. In fact all the marble for the Stadium of Athens, also paid for by Herodes Atticus, also came from his personal quarry, although the Panathenaic Stadium of Herodes is long gone. The new version was built in the late 19th century and refurbished for the Athens Olympic Games in 2004.

The Odeon of Herodes was destroyed in 267 sack of the city by the Heruli. There were a few restoration attempts in 1898, 1900 and 1922. During World War II the Odeon hosted performances by the Greek State Orchestra and the Greek National Opera. One of these performances featured a young Maria Kalogeropoulou who would later become famous as Maria Callas.

The theater was restored between 1950 and 1955 and is currently the home of the Athenian home of the Athens and Epidaurus Festival from June through August, showcasing everything from Classical to Pop music, from Frank Sinatra, to Jethro Tull, Sting, Luciano Pavarotti, Nana Mouskouri, Elton John, Yanni, Diana Ross, Andrea Bocelli and the Foo Fighters.

Theater of Dionysus Eleuthereus

On the southern slope of the Acropolis Hill, behind the Parthenon is the Theater of Dionysus Eleuthereus. Built in the 6th century BC, it once stretched up the hillside to the top of the Acropolis Hill and held a capacity of 16,000 people. This was the home of the Greek Dionysia, honoring the god Dionysius with Greek theater.

When Mark Antony and Cleopatra came to Athens around 34 BC they were honored by the Athenians who gave them one million drachma for their war chest in the coming war against Augustus. The Athenians gave Mark Antony the title of Dionysius and Cleopatra the title of Ariadne. They also performed a wedding ceremony where mark Antony (Dionysius) was married to the goddess Athena. All of this was to give Antony and Cleopatra favor with the gods to defeat Augustus in the coming war.

A short time later, during a bad storm in Athens, a statue of Dionysius fell into the Theater of Dionysius Eleuthereus and smashed into pieces. It was a foretelling of what was to come. On September 2, 31 BC, Mark Antony was defeated at Actium, off the eastern Ionian coast of Greece.

In the 1st century AD, The Emperor Nero made some restorations.

Nero came to Greece in 66 AD. His visit mostly involved his participation in the Olympia Games. Every event he entered was fixed so he would win. In the ten horse chariot race, he fell out of the chariot twice and never finished the race, and yet, he was declared the winner. He even created a music competition, which, of course, he won.

The Neronian renovations to the Theater of Dionysus Eleuthereus could have been facilitated at the same time he came to the Olympia games although there are no records of Nero performing at the theater.

In the 2nd century, the Emperor Hadrian put a lot of money into the theater.

In the year 125, Hadrian presided over the Dionysia Festival in the Theater of Dionysus Eleuthereus.

At that time there were 12 statues of Hadrian set around the theater. The bronze statues are gone but 4 of the pedestal (with dedication inscriptions) still remain.

Hadrian created a large sculptured Skene (scenic wall) upstage of the orchestra that illustrated the attributes of Dionysius. Only the lower level of the wall remains today but you can still get a good image of the life of Dionysius from his birth to his elevation to a god.

The high backed stone seats around the orchestra were added between the 1st and 2nd centuries.

On the centerline of the cavea (seating) is a high back throne. Although this appears to be the Throne of the Emperor, the actual Emperor’s Throne would have been places on one of the marble pedestals adjacent to the carved throne.

The Greek influence on the Emperor Augustus

In the time of Augustus, 4th and 5th century BC classical Greek art was the rage in all the aristocratic families of Rome. If the originals were too expensive, Roman copies or plaster casts were more affordable.

By the 4th century AD, there were as many statues in Rome as there were people. They filled theaters, temples, public baths and homes. They were painted to appear lifelike.

Athens and the entire Roman Province of Achea was a great producer for Rome, providing, pottery, linens, cosmetics, olives and olive oil, copper, lead and silver. It was also a great source of educated slaves who served Rome as Educators and Medical Doctors.

Augustus founded the first Roman Medical Corp, trained Doctors who would operate field hospitals and provided triage on the fields of battle. If you wanted to practice medicine in the time of Augustus, you had to pass the exams at the Roman Medical School. Upon retirement, these trained Doctors received land grants and gifts. Many of same practices and medical tools of ancient Rome are similar to the tools used today.

Medical practices were pretty unreliable prior to Augustus. Pliny the Elder claimed that a common phrase inscribed into Roman tombstones was, “It was the crowd of physicians that killed me.”

In 23 BC, Augustus was dying from a fever. All his appointed doctors failed to find a cure.

His life was finally saved by a Greek doctor named Antonius Musa, who just administered cold compresses.

Most likely the fever that almost killed Augustus just ran its course and Musa showed up at the right time. Nonetheless, Antonius Musa was elevated to the status of demigod.

This statue of Antonius Musa is in the Vatican Museums.

Hadrian in Athens

In my section on the Roman Agora, I wrote about the Forum of Hadrian (known as the Library of Hadrian). In the section describing the Theater of Dionysus Eleuthereus, I added a little more of the time of Hadrian in Athens. They just seemed like the right places to include him. However, there is so much more to Hadrian’s Athens.

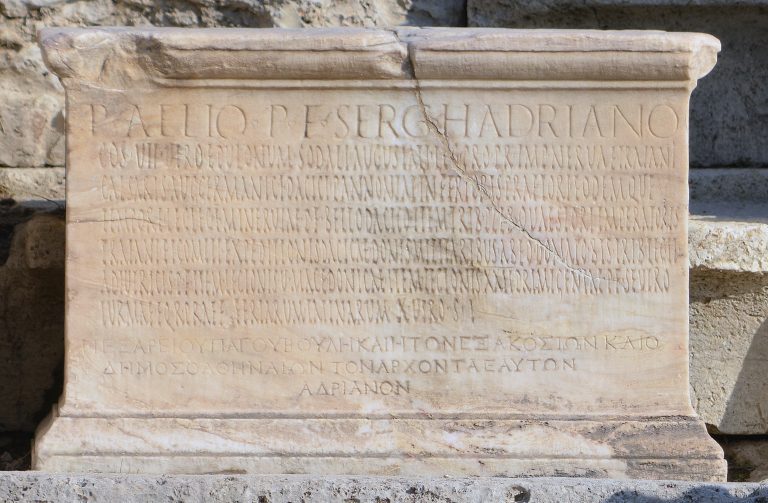

Hadrian was the first Emperor to grow a beard in deference to the Greek philosophers. He wrote poetry in Greek as well as Latin and spent much of his time in the pursuit of philosophy, knowledge and architecture. It was Hadrian who designed and built the current version of the Pantheon in Rome. Although Apollodorus of Damascus is often credited with the design, I believe it was all Hadrian. Apollodorus mocked Hadrian’s domes. I highly recommend a visit to Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, about 20 miles from Rome, to get an idea of the brilliance of Hadrian’s architecture.

Hadrian made three visits to Greece, in 124, 128 and 131. In fact, he spent most of his time as Emperor away from Rome, preferring to travel the Empire or stay at his Villa in Tivoli.

In these three visits to Athens he lavished money and large doles of grain to the Greeks in exchange for their love and loyalty.

Athens had such regard for Hadrian, they gave him the honor of “Chief Official” five years before he even became Emperor.

One his first projects was to bring water to Athens. A reservoir was created on top of Mount Lycabettus, the highest mountain in Athens and then channeled the water down into the city. The aqueduct mostly ran underground.

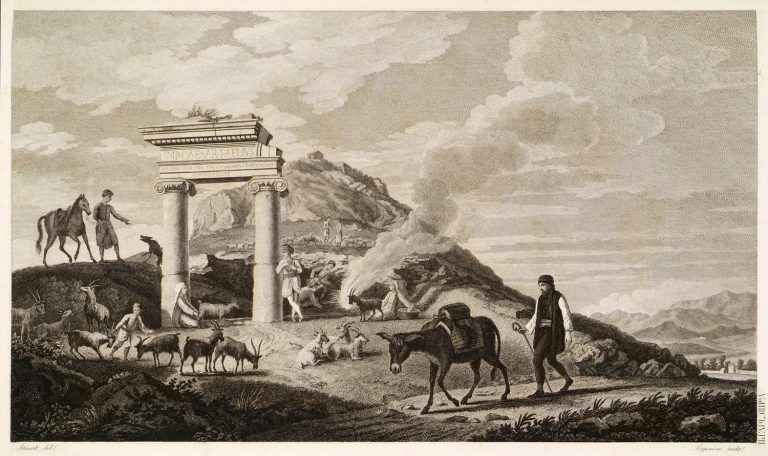

This is a drawing by Stuart and Revett from 1794 that shows the remains of the aqueduct arch on Mount Lycabettus.

This is the same piece of the architrave, now sitting in the National Garden.

Hadrian’s New Athens

Hadrian’s new Athens was sometimes referred to as Hadrianopolis, not to be confused with the 13 other Hadrianopoleis throughout Turkey, Syria and northern Africa.

The remains of the new city around the Sanctuary of the Olympieion, the Temple of Olympian Zeus is situated about 300 meters (328 yds) east of the Acropolis Hill. This is a google map view, bordered by the large avenues of Leoforos Vasilissis Olgas, Leoforos Vasilisis Amalias, Leoforos Andrea Siggrou and Leoforos Athanasiou Diakou.

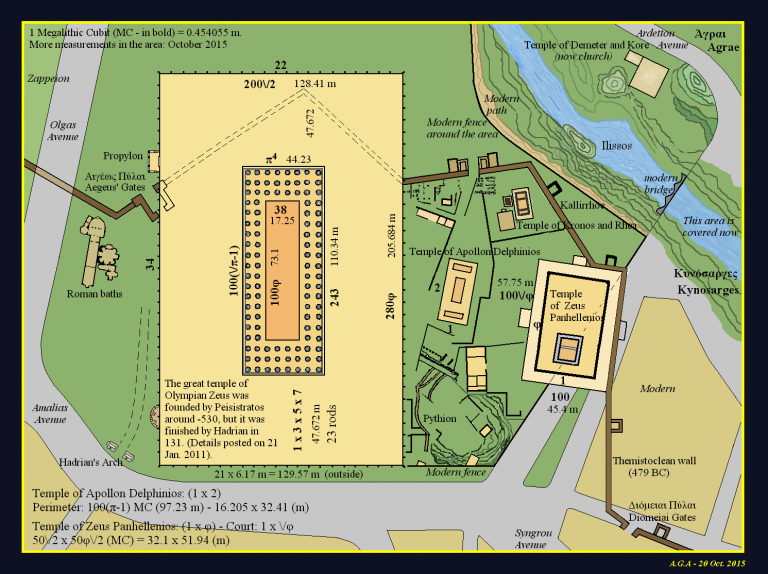

In the plan view above you can see they layout of The Temple of Olympian Zeus, the largest temple in the known world, the Temple of Panhellenios Zeus (now gone), the Arch of Hadrian, the Baths of Hadrian, the Temple of Apollon Delphinios, the Temple of Kronos and Rhea and other pieces that no longer exist.

The baths (above) made it into the 7th century but all that remains now are some column bases, marble floor tiles and room foundations.

The baths (above) made it into the 7th century but all that remains now are some column bases, marble floor tiles and room foundations.

However, the New City was more than the Sanctuary of the Olympian Zeus. Hadrianopolis would have extended into the Agora and Hadrian’s Forum/Library.

Between 256-260, the Emperor Valerian, fearing attacks from the Goth, fortified a wall around the New City. Emperor Valerian ended up being captured and tortured by King Shapur I of Persia in 260. Before Valerian was killed, he was used as a human footstool for Shapur to mount and dismount his horse. Shapur had Valerian’s skin stuffed with straw and preserved, dragging it around to various parts of the Persian empire as a trophy.

The wall of Valerian didn’t do much better than the Emperor. Seven years after it was constructed, it was breached by the Heruli in 267.

The Arch of Hadrian

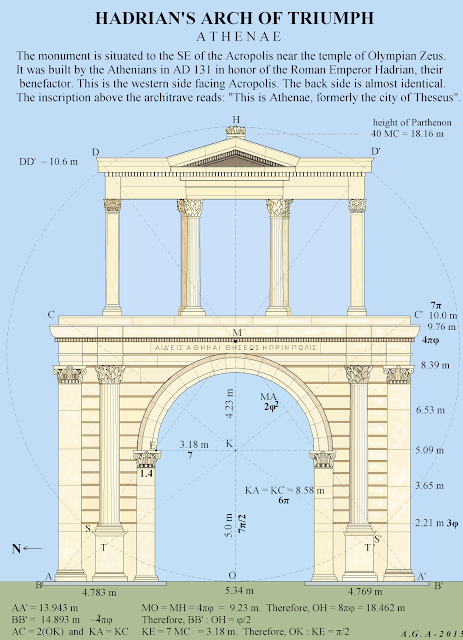

The Arch of Hadrian (Hadrian’s Gate) was/is the gateway arch that connected the old Athens founded by Theseus to the new Athens founded by Hadrian.

On the top of the arch were two statues that corresponded to the inscriptions below.

One side translates to “This is Athens, the ancient city of Theseus.

The other side translates to, “This is the city of Hadrian and not of Theseus.

The Arch is built from the same pentelic marble (from Mount Pentelikon) as the Parthenon.

The 18 meter (59′) tall x 13.5 meter (44.3′) wide x 2.3 meter (7.5′) deep arch was created using clamps to tie the stones together. It was buried by the ages with barely 3′ above the ground. This is what kept it in such great condition. Unfortunately, the arch sits on the main thoroughfare of Leoforos Vasilisis Amalias Street. Over the years the pollution of the city has done some severe damage to the sculpture and stone.

Temple of Olympian Zeus

The Temple of Olympian Zeus was conceived and started around 520 BC by Hippias of Athens who wanted to create the largest Temple in the known world. Ten years later, however, Hippias was forced out by the Spartans and the project died.

Hippias, by the way, fled to Persia where he petitioned King Darius I to invade Greece and put him back on the throne. Darius agreed but it didn’t turn out well. The Persian Army was defeated at the 490 BC Battle of Marathon.

In 174 BC, Antiochus Epiphanes IV, the Seleucid King and self proclaimed embodiment of Zeus on Earth, revived the project, with a design by the Roman architect, Decimus Cossutius, who was quite possibly a Romanized Greek from one of the Magna Grecia colonies absorbed by Rome in the 3rd century BC.

In 168 BC, Antiochus Epiphanes IV was about to invade Alexandria until he met up the Roman Ambassador Gaius Popillius Laenas who drew a circle around Antiochus and told him if he crossed the line, he’d be at war with Rome. Instead of defeat, Antiochus IV went back to Daphne (near ancient Antioch in Turkey) and staged a victory triumph parade that included 50,000 soldiers (according to the Greek historian Polybius).

For all you Biblical fans, Antiochus Epiphanes IV was the King who persecuted the Jews in Jerusalem and caused the Maccabee revolt (167-160 BC) which gave birth to the festival of Hanukah.

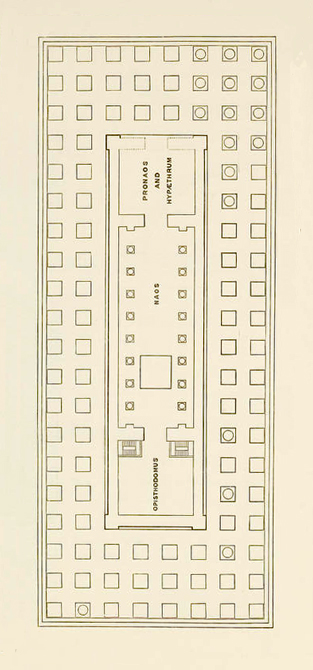

The Temple of Zeus was proposed to have 3 rows of 8 columns across the front and back of the Temple and a double row of 20 columns on the sides, a total of 104 columns with Corinthian capitals, all over 56′ tall. Although the construction was well underway, when Antiochus IV died in 164 BC from fighting the Parthians, the Temple of Zeus was once again put on hold.

When Lucius Cornelius Sulla sacked the city in 86 BC, he saw these 56′ columns and said, “I’m taking these babies back to Rome”.

He took a couple of them and placed them in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus in Rome. There are many historians who believe these columns started the rage of the ornate Corinthian design in Rome.

The construction of Olympian Zeus stayed on hold for another 288 years until the Emperor Hadrian arrived to Athens on his first visit as Emperor.

Hadrian used the architectural plans of Decimus Cossutius, the same Roman Architect who design the Temple for Antiochus Epiphanes IV in 174 BC.

When the construction was finally finished In the year 131, it was dedicated to Hadrian, who took the title of ‘Panhellenios’, the supreme leader of the all the Greek States.

The Temple had two statues, one greatly adorned Chyselephantine Zeus modeled after the Pheidias statue of Zeus in Olympia (home of the Olympic Games) and the other of the Emperor Hadrian. The dedication of the temple also included a snake brought from India as an offering to Erichthonius, the serpent god who lived in the Erechtheium on the Acropolis.

When the Heruli sacked Athens in 267, the Temple was stripped. It never recovered. A hundred -fifty years later, Roman temples were illegal. The Temple of Olympian Zeus was harvested for stone.

Today only 15 of the 104 columns remain. They are enormous, 17.25 meters tall (56.5′). The Parthenon columns of the Temple to Athena are 10.4 meters tall (34′).

For a more in depth review of Hadrian’s works in Athens I’ll defer to Carole Raddato’s excellent website Following Hadrian. This is her entry on Hadrian in Athens.

Monument of Philopappos

There is one more monument from Roman times known as the Monument of Philopappos.

It is a Greek Mausoleum dedicated in the year 116 to Gaius Julius Antiochus Epiphanes Philopappos, Roman Consul and patron of the arts and games.

It predates Hadrian as Emperor by one year and thus built in the last year of the Emperor Trajan. However, Philoppapos was very friendly with Hadrian and Sabina.

Philopappos was the son of the King of Commagene (ancient Armenia). Antiochus IV, King of Commagene backed Vespasian to be the new Emperor of Rome after Nero, during the year of four Emperors. He also lent his armies of Commagene to support Vespasian during the Judean-Roman War between AD 66-73. When Vespasian did become Emperor of Rome one would think Antiochus IV would have a pretty cushy spot by his side. But somewhere in the mix, Antiochus was accused of siding with the Parthians, an enemy of Rome, and Vespasian removed him from his throne. Eventually they two made up but not enough to give Antiochus back his Kingdom. Instead King Antiochus IV moved his family to Rome and lived a very comfortable life.

Even with no kingdom, Prince Philopappos’ royal pedigree gave him elite status and when he came to Rome he used his influence to become a Senator and Suffect Consul of Rome, basically a Consul in waiting. If a Consul died or was removed, there were extras to take his place. He eventually moved to Athens where he was known for his gifts to the arts, his sponsorship of the games and his extravagant tastes.

His younger sister, Julia Balbilla, was a poet and friend of both Hadrian and his wife Sabina. When Philopappos died in 116, it was Julia Balbilla who paid to erect the monument on the Mouseion Hill (Hill of the Muses), southwest of the Acropolis Hill. The Hill is known as the Philopappu Hill these days, named for the monument.

Roman didn’t bury people on hills. The buried their dead on flat ground. According to Professor Diane E.E. Kleiner, the mountain top mausoleum is in deference to the ancestry of Philopappos’ family, who did have tombs built on towards the apex of mountain tops.

Regardless of why or how he got his tomb up here, he commands one of the best views in the city.

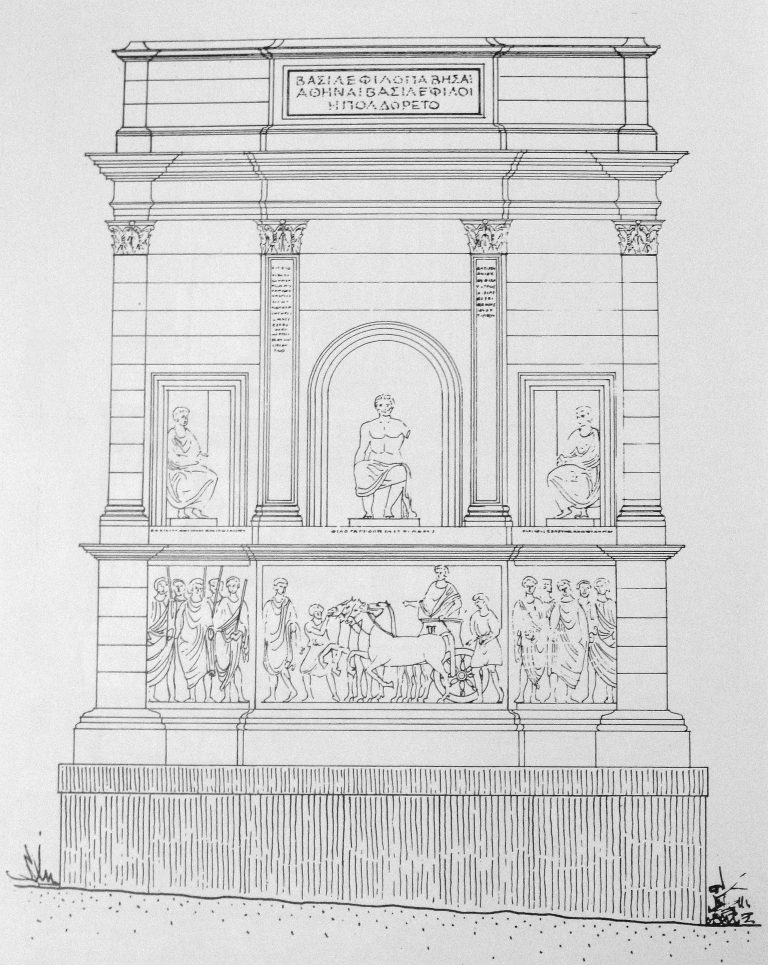

The two story monument has a frieze on the lower level with Philopappos as a Consul of Rome riding in his chariot led by lictors, the officials who accompanied a Consul and executed sentences on convicted offenders. The upper level shows the torso of Philopappos in the center.

On the left is the torso of Antiochus III Epiphanes, the grandfather of Philoppapos. In fact, the name Philoppapos means fondness of his grandfather, in reference to Antiochus III Epiphanes of Commagene. .

On the right of Philopappos was a statue of Seleucus I Nicator, one of the Generals of Alexander the Great, but it’s been long gone.

The Monument stayed intact until the fall of Constantinople. There are records of Ciriaco de Pizzicolli who wrote about the monument in 1436. Ciriaco, a recorder of Greek and Roman antiquities is sometimes referred to as the Father of Archeology.

The Monument and the Philopappu Hill are now declared an Archeological Park and wildlife preserve. It has become the indigenous home of the Athenian owl and the Peregrin Falcon.

On a final note, I would like to thank my friend and guide through Roman Athens, Aristotle Koskinas. Aristotle is an archeologist and lover of all things Classical. He is an expert of ancient roof tiles, a raconteur of amazing tales and one of the best guides you could ever hope to find. You can reach him at https://aristotleguide.wordpress.com/

Here is a photo of Aristotle at the Balomenee column on the porch of the entrance to Hadrian’s Forum/Library. The Balomenee (mended column) has been the traditional meeting place for Athenians for hundreds of years.

You must be logged in to post a comment.